Reported by

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a busy stretch of toll road links the capital Kinshasa, one of Africa's most populous cities, to the country's short coastline.

Since 2008, the government has contracted a Chinese consortium to manage the half-a-billion dollar expansion and improvement of the highway, known as RN1. While the construction is slated to finish next year, some commuters are unimpressed.

Truck driver Paul Mavinga says the road is too narrow, making it difficult for vehicles traveling in opposite directions to squeeze past. The toll fee he pays “could be used to widen the road, because it's a necessity," he says. "The narrowness of the road contributes to accidents and traffic jams.”

Cracks and potholes also make for a bumpy ride.

“For large trucks, it's a little less difficult, but for those who use motorcycles as a means of transportation, it's much worse,” says Christine Luzolo, who lives near a portion of the road that runs through Kongo Central province.

At the entrance to the town of Kimpese, the RN1 highway shows cracks, potholes, no road markings, overgrown vegetation on the sides, and worn pavement—signs of poor maintenance.

Local concerns over the road’s quality are not the only issue.

Documents obtained by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF) and shared with OCCRP, Actualite.cd, De Standaard, and Le Soir indicate that one of the companies subcontracted by the Chinese consortium to work on the road was partially owned by a Congolese politician and his family members.

DRC Minister of State for Regional Planning Guy Loando and his wife held more than a third of the subcontractor’s shares when it signed its first $25 million roadworks contract in June 2019. The company, called SIC, had only been formed a month earlier.

At the time, Loando was serving as a senator in the Congolese parliament. A month after SIC was awarded its first project, the 42-year-old and his wife transferred their stake in the company to a man named Baby Mambo Kapaye — who is no stranger to the Loandos. Reporters found he is married to Loando’s wife’s sister, and has held a number of roles in companies and organizations owned and controlled by Loando.

When reached for comment, Loando and Mambo Kapaye confirmed their familial ties but declined to answer questions about whether Mambo Kapaye had been acting as a proxy for Loando in SIC. It is unclear whether Mambo Kapaye made any payment for the shares, and neither he nor Loando responded to questions about the transfer.

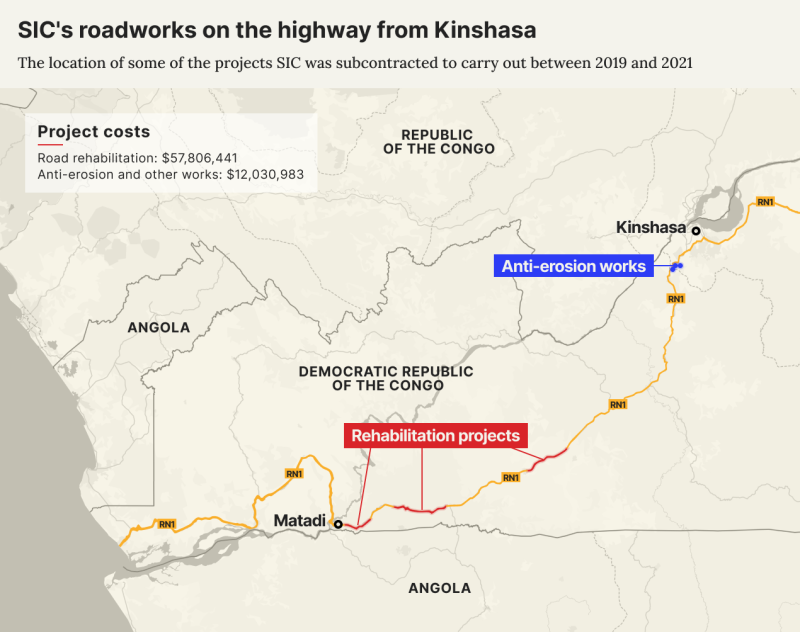

SIC was awarded at least six more projects worth $44 million to carry out rehabilitation and anti-erosion works on the highway between 2019 and 2021, the year Loando was appointed to President Felix Tshisekedi's cabinet with a broad portfolio spanning the infrastructure, energy, and health sectors among others. (There is no evidence that he has used his official position to influence the awarding of any public works contracts.)

Loando told OCCRP that he “received no personal benefit” from SIC as he was not a shareholder. He declined to answer any other questions about the firm. Mambo Kapaye said he would not answer any questions about SIC by phone and referred reporters to Loando.

When presented with the findings, Transparency International’s vice-chair Ketakandriana Rafitoson said the arrangement could give the appearance that a government official was "building a facade" to obscure any potential benefit from a commercial activity. She added that it gave the impression of a family’s apparent “capture of a public contract,” and described the share transfer as a textbook example of a possible “conflict of interest.”

It is not clear how the Chinese consortium in charge of the project, which is led by a company named SOPECO, selects subcontractors like SIC, and whether there was any competitive bidding process. The government and SOPECO did not respond to requests to comment.

Yet Loando has long-standing ties to SOPECO’s owner, the Chinese business magnate Cong Maohuai. Loando previously served as a lawyer for Cong, a well-known investor in the DRC who goes by Simon, and has publicly referred to him as a “mentor.”

Ongoing rehabilitation work on the Kinshasa–Matadi highway, financed by SOPECO in February 2025, has narrowed lanes and slowed traffic.

This is not the first time that Cong has come under scrutiny for his firm’s management of the RN1 highway.

An internal 2021 document obtained by PPLAAF from the government’s financial watchdog, the Inspectorate General of Finance (IGF), alleged that the Cong-led consortium failed to declare millions of revenue collected from tolls on the road. It also alleged that the budgets for construction projects on the highway — including two stretches of road that SIC was subcontracted to work on — had been inflated by as much as $48 million.

The IGF did not answer OCCRP’s queries on the report, including whether its findings were forwarded to the relevant authorities.

Cong did not respond to requests to comment and Loando, who is not mentioned in the IGF report, said he was unaware of the probe and emphasized that he has never been the subject of any prosecution.

Richard Messick, a longtime expert who previously worked with the World Bank on anti-corruption and governance issues, said the findings raise “numerous red flags.”

The DRC government “should commission an independent audit of the deal,” he said, “so that citizens and international partners, including the IMF and the World Bank and the African Development Bank, can evaluate whether to continue assistance on infrastructure given the way this is set up.”

The government agency overseeing the country’s public infrastructure projects, the Agence Congolaise des Grands Travaux (ACGT), did not respond to a request to comment.

The Congo’s Road King

The tollway from Kinshasa is one piece in a $4 billion infrastructure portfolio the DRC has pursued since 2006, when former president Joseph Kabila won an election with the promise to build roads, hospitals, and schools across the impoverished and war-torn country.

Some of these projects are being bankrolled under what is known as a “minerals-for-infrastructure” bargain, in which Kabila gave Chinese state-owned enterprises rights to the country’s copper and cobalt deposits in exchange for carrying out the public works.

But the vast majority of the funds spent on highways in the DRC, including the one from Kinshasa, come from concession contracts in which private firms finance and manage public works and then recoup the costs through user fees, like tolls, or government payments.

Cong and his firm SOPECO have been major players in the concession market, winning around a third of the contracts by value, according to the latest report from the ACGT.

With investments that span mining, electricity generation, and construction, Cong has been a fixture of the DRC’s business scene for decades. He is heavily involved in roadworks — projects that all together cost more than $1 billion — covering three key transportation routes in the DRC; in addition to the tollway connecting Kinshasa to the coast, his company has been modernizing links between the country’s main mining area and business hub, as well as an overland route for exports.

According to Chinese records, Cong landed in the country following a late-1990s Chinese government policy that urged companies and entrepreneurs to invest abroad. Loando, then a young lawyer specialized in the mining sector, took Cong on as a client and accompanied him on his commercial forays.

Loando still describes Cong as central to his career. “Mr. Simon is humble, wise and full of vision,” he says on the website of his charitable foundation, adding that the Chinese businessman is “one of few people” to have understood his vision.

Geraud Neema, a nonresident scholar in the Carnegie Africa Program and an expert on DRC-China relations, says that serving as Cong's lawyer likely helped Loando build valuable relationships that would ultimately support his entry into politics.

Loando “is very much the result of Simon,” said Neema. “Simon really made him who he is today.”

Previous brushes with controversy

This is not the first time that Loando has been named in reporting that raised questions over his business deals in DRC.

A “Chinese Company”

The Kinshasa highway toll road is by far the most expensive project undertaken by Cong’s company SOPECO in the DRC.

In 2010, a prior concession contract budgeted $138 million for the works. But that figure ballooned to $514 million in 2016 as the project expanded to include additional features — including the anti-erosion control and other rehabilitation efforts that were subcontracted out to SIC.

Tracking down information about SIC’s background is not easy. The ACGT has referred to SIC only as a “Chinese company” on social media, and provided an incorrect rendering of the company’s full name in its promotional magazine, reporters found.

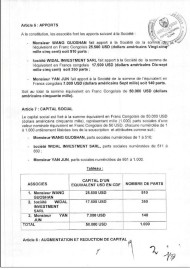

After confirming SIC’s full name — Société d'Ingénierie et de Construction (Engineering and Construction Company) — and obtaining its articles of incorporation, reporters learned that the company’s owners did in fact include two Chinese nationals, who have experience in road-building and owned 65 percent of the company between them. Yet the documents also show that the remaining 35 percent was held by a local firm called Widal Investment — which belonged to Loando, his wife, and their children.

Connecting SIC to the Loando family

Loando and his wife collectively held 10 percent of the shares in the company, which has since been renamed L-Investment, with the remainder held by the couple’s three young children, the eldest of whom is 14. Loando is identified in company documents as representing the interests of his children, indicating he and his wife have complete control of the firm and are its beneficiaries.

On SIC’s articles of incorporation, Loando's wife is named as the representative of Widal, but her signature is nowhere to be found. Instead, Loando signed and initialled nearly every page. His law firm is also listed as SIC’s legal representative. When asked about his signature on these documents, Loando said it was “private and confidential information.” Lawyers who previously represented the other two initial shareholders did not respond to requests to comment.

According to records of a shareholder meeting, a month after SIC had secured its first deal on the Kinshasa highway project, Widal ceded its 35 percent of the company’s shares to Mambo Kapaye, in July 2019.

Documents Differ Over Transfer Date

In addition to their familial connection, Mambo Kapaye has numerous business links to Loando and his enterprises: he managed Widal’s real estate operation, and served as its representative to a mining subsidiary. Mambo Kapaye also sat on the board of Loando’s charitable foundation alongside Loando and his wife.

After its first $25 million deal, SIC was awarded two more for the highway project worth $14 million, according to the ACGT’s 2019 annual report. The report doesn’t state when these projects were awarded. In 2020 and 2021, SIC was listed as the subcontractor for four additional projects worth $30 million.

While the ACGT's most recent annual report from 2023 no longer includes details about subcontractors' specific projects, a video published by the agency in February 2025 notes that SIC was working on efforts to widen parts of the road leading to tollbooths and weigh stations.

A video published by the ACGT on in February 2025 highlights SIC's work to widen parts of the road.

Tim Zajontz, a senior lecturer in international relations at the University of Freiburg who has researched Chinese-run infrastructure projects in Africa, said the presence of a politically connected subcontractor in the highway project was “not very surprising."

Many of the local contractors profiting from Africa’s infrastructure boom “are owned by business people with close ties with influential figures in government or by politicians themselves,” he said.

“Their links to influential officials commonly shield these firms from public oversight or criminal prosecution.”

‘Embezzled’ Revenue and Inflated Contracts

SIC continued to execute public works after President Felix Tshisekedi appointed Loando to his cabinet in April 2021. But just days after Loando was named Minister of State for Regional Planning, his mentor was heavily criticized in a document produced by the state’s financial watchdog, the IGF.

The April 2021 report, never publicly released but obtained by reporters, alleges that Cong’s SOPECO and its Chinese partner in the consortium failed to declare some $193 million in revenue collected from tolls on the Kinshasa road.

Maintenance work being carried out at the Lukala toll station.

Citing banking data, the watchdog asserts that “this concealment of revenue constitutes a misappropriation of public funds.” It recommended “legal proceedings for embezzlement of public funds” against Cong and 22 government officials described as potentially “complicit.”

The same document also alleges that the costs for certain construction projects on the highway — including work on two stretches of road that were outsourced to SIC — were inflated by $48 million. The report cites discrepancies between the fixed costs of the projects in contracts between SOPECO and the government, and the amounts ultimately invoiced for the work.

“The contract amounts are far overestimated in relation to the actual cost of the amounts of the work carried out. This indicates a lack of prior studies,” reads the report.

The document notes that Cong’s consortium did not respond to the allegations raised by the agency, while the ACGT said it expected the invoices to match the contract costs once those projects were closer to completion. The ACGT did not respond to OCCRP’s requests to comment.

The IGF, which is tasked with overseeing the DRC’s public finances, revenue, and spending, has identified hundreds of millions of allegedly misappropriated funds in its investigations over the years.

But it has reported difficulties in executing its mission, including understaffing and a lack of resources. The courts present another hurdle, with the DRC’s judiciary notoriously hampered by underfunding and systematic corruption.