Pangolins, including eight species of scaly anteaters found across Africa and Asia, are the world’s most trafficked mammals.

The report identified 924 online advertisements of pangolin-derived products, the majority of which were found on websites serving the Chinese market. Some advertisements were also found on websites that offer to ship their products internationally.

Trafficking is driven by the use of pangolin parts in traditional Chinese medicine.

According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, the equivalent of around 141,000 live pangolins was seized in 2018. In Central Africa alone, which became the epicentre of the global pangolin trade after a near disappearance of the species from the Asian range states, between 400,000 and 2.7 million pangolins are estimated to be poached every year.

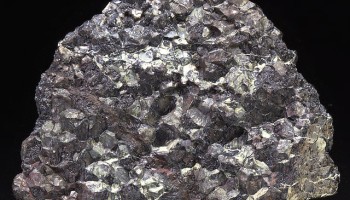

Traditional Chinese medicine mostly uses pangolin scales, believed to stimulate lactation and reduce swelling. Harvested from killed pangolins, scales are typically fried and then processed into tablets, creams and different types of liquids. Another popular ‘medicament’, pangolin wine, is produced by boiling baby pangolins in rice sake.

The international trade in pangolins and their parts, regulated since 1975, was effectively banned in 2016 with the inclusion of all the recognised pangolin species in CITES Appendix I, permitting specimens to be traded only in exceptional circumstances. That said, China has maintained a legal domestic pangolin market.

Officially, wildlife products are obliged to have the China National Wildlife Mark (CNWM), proving legal and sustainable sourcing of wildlife products. But the report found that most pangolin products lacked it.

The websites often operated as mere agents, directing users to other online advertisements, with evident motivation to avoid these regulatory restrictions. Advertisements in English, serving the international market, then tend to obfuscate the inclusion of pangolin ingredients, which could make their sales illegal under CITES.

To curb the practice, the report urges China to undertake a much stricter implementation of existing safeguards. “Chinese authorities must take all actions to ensure complete supply-chain transparency on the pangolin-derived traditional Chinese medicine market,” it says.