The Cullen Commission, an 1,800-page report written by Commissioner and former B.C. Supreme Court Justice Austin Cullen, was drafted following significant public concern about money laundering in the province.

Cullen’s task was to evaluate the extent to which money laundering had infested various sectors of British Columbia’s economy as well as evaluate the effectiveness of regulatory and law enforcement agencies in their anti–money laundering efforts.

What he concluded was that “an enormous volume of illicit funds is laundered through the British Columbia economy every year.” The Commissioner cited a model which indicated that CDN$6.3 billion (US$4.8 billion) had been laundered through the province in 2015, with an additional CDN$7.4 billion ($5.7 billion) laundered in 2018.

Cullen further sought to paint money laundering as not just an example of white-collar crime that concerns only the elite and uber wealthy. He noted that it is never the first link in criminal activity; the proceeds are first generated by crimes that destroy communities such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, and fraud.

“These crimes victimize the most vulnerable members of society,” the former B.C. Supreme Court Justice wrote.

Canada’s agencies mandated with analyzing information pertaining to money laundering threats received considerable criticism in the 1,800-page report.

One critique focused on the the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), which concluded that the agency failed to disclose thousands of intelligence reports to law enforcement bodies, whose investigations could have benefitted from access to such information.

Cullen noted that, in 2019–20, FINTRAC received over 31 million individual reports, but disclosed only 2,057 to law enforcement across Canada, and only 355 to authorities in British Columbia.

“Law enforcement bodies in British Columbia cannot rely on FINTRAC to produce timely, useful intelligence about money laundering activity that they can put into action,” the Commissioner observed.

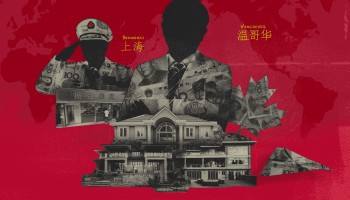

One noteworthy example of money laundering activity that went unnoticed by authorities is Chen Runkai, a Chinese property developer who transferred tens of millions of dollars across hundreds of wire transfers without attracting any suspicion from Canada’s banks.

A previous report by OCCRP and the Toronto Star noted that before moving to Canada in 2006, Chen earned a modest salary of CDN$41,000 ($31,658) per year, yet no red flags were raised concerning the sums Chen had transferred nor was the country’s financial regulator even made aware of his activities.

“All kinds of alarm bells should have gone off,” said Garry Clement, a former Royal Canadian Mounted Police superintendent focused on investigating the proceeds of crime. “It almost gives the impression they’re asleep at the switch…It just shows that the system is broken.”

Chen was also the focus of a more in-depth investigation by OCCRP and the Toronto Star into money laundering activity flowing in from China into Vancouver’s real estate market.

What was discovered was that not only had CDN$114 million ($87.9 million) been deposited into Chen’s bank account a few years after moving to Canada, but that he was also wanted for arrest by the Chinese government on bribery charges for his alleged role in a major corruption scandal involving a senior military official.

The scandal raised serious concerns about the due diligence employed by Canadian banks in their efforts to properly detect money laundering activity and subsequently report it to the proper authorities.

When asked for comment, the banks cited privacy concerns on speaking about individual clients.

Canada’s politicians, on the other hand, were more vocal of the country’s shortcomings in its fight against money laundering.

“Canadians are struggling to afford housing in cities across Canada, but the government is still allowing illicit foreign funds to make things even worse,” said Member of Parliament Alistair MacGregor in an address to the House of Commons.

“For eight years,” the MP said, “Chinese property developer Runkai Chen used wire transfers to launder tens of millions of dollars into Canadian banks. Canada has a broken system for tracking money laundering. The lack of action from this government only brings more hardship for everyday Canadians.”

Immediately following the release of the Cullen Commission, Canada’s Department of Finance published a statement on its commitment to protecting Canadians and the country’s economy from money laundering.

“The federal government takes the issues of money laundering and terrorist financing very seriously,” the statement read. “The government will closely examine the report and continue working with all partners, including the Government of British Columbia, as part of its efforts to review and improve Canada’s Anti-Money Laundering and Anti-Terrorist Financing (AML/ATF) Regime.”

Cullen’s investigation shed further light on the risks banks are faced with when dealing with potential money launderers. He explained that the banks are responsible for processing so much of the country’s assets that it is impossible for them to ensure due diligence is done on every transaction.

“As of 2015, banks held over 60 percent of the financial sector’s assets, by far the majority of which were held by the six largest domestic banks,” the Commissioner wrote. “Provincial credit unions and caisses populaires also handle vast sums of money – $320 billion in assets as of 2014.”

Cullen submitted recommendations in his report on how the country may better identify money laundering threats in the future. One such recommendation was the creation of a dedicated provincial money laundering investigation unit with a well-equipped intelligence division.

“If the province is to achieve success in the fight against money laundering,” he wrote, “it must develop its own intelligence capacity in order to better identify money laundering threats.”

Canada’s federal government wasted no time in naming this new agency, as well as ensuring that its watchdogs and law enforcement organizations will receive the investments they need to combat money laundering going forward.

The country’s 2022 budget will allocate CDN$89.9 million ($68 million) in funding for FINTRAC over five years, the Department of Finance statement said.

Additionally, the government revealed its intent to form a new Canada Financial Crimes Agency, which it said will bolster the country’s ability to quickly respond to complex and fast-moving cases of financial crime.