“We were in panic because all the sources were telling us: don't write this story,” says Musaieva. “And it (the panic) still lingers,” chimes in Akymenko, her partner.

Vladimir Fedorin, chief editor of Forbes Ukraine magazine until July, confirmed that the journalists “were pressured obscenely” by associates of Serhiy Kurchenko, the target of the journalistic investigation.

Kurchenko would not be interviewed for this story. But he has told others that journalists have nothing to fear from him and has denied any threats.

So who is Kurchenko? And where did he come from? The unlikely young multimillionaire rose to national prominence in just a few years following the election of President Viktor Yanukovych in 2010.

At the time, Kurchenko’s companies were winning lucrative government tenders to buy liquefied gas at a discount, and the companies’ gasoline trade was ballooning. Such a speedy rise in Ukraine often suggests high government connections.

Musaieva and Akymenko, both 26, took on the first comprehensive investigation of Kurchenko's business, spending months untangling webs of seemingly unrelated companies, knocking on the doors of their directors and plowing through databases to find the hidden patterns in business schemes.

The resulting report, “The Gas King of All of Ukraine”, came out last year on Nov. 12 on Forbes Ukraine's website. A version of the story was published in the December print edition of Forbes magazine and posted online. The two stories have collected over 300,000 hits on the forbes.ua website to date.

Fedorin, chief editor of Forbes Ukraine magazine until mid-2013, says Kurchenko's associates who came to meetings to answer some of the journalists' questions repeatedly warned them not to pursue the story.

It was not the first time Forbes staff said they were threatened by a Kurchenko-related company. Leonid Bershidsky, the then-chief editor of the online version of Forbes, says the publishing company also received “official threats of legal prosecution that arrived from the group Gaz Ukrainy 2009,” the predecessor of Kurchenko's current holding.

There were good reasons for the Forbes reporters to be scared: attacks on journalists, including investigative journalists, really happen in Ukraine. In 2011, an investigative journalist was shot in the head in Ukraine. Another found the door of his home set on fire.

According to the latest report on freedom of speech, published in August by the local media watchdog Institute of Mass Information, in the first seven months of 2013 there were 29 incidents of attacks and beatings of journalists, 80 cases of interference in journalists’ performing their duties, 19 cases of pressure and threats and five instances of journalists being detained.

Last June, the journalists were shocked to find that the subject of their investigation had bought Forbes and 50 other brands in UMH Group, one of the nation’s leading media companies. The reported $340 million deal was announced in June. Kurchenko is expected to take control next spring, when the final payment is made.

The change in ownership prompted the exit of Musaeva, Akymenko and some of their colleagues, including Fedorin, from the magazine.

Kurchenko has denied threatening the journalists attempting to investigate him. In an interview for Forbes published on July 1, Kurchenko said that at the time his company had outsourced communication, and if anyone was at fault for pressuring journalists, he would “punish the guilty.” He did not respond to requests to comment for this story.

Kurchenko says he has big plans for the media company. He has pledged to invest $100 million into his new business. He also promised to preserve editorial independence of its news publications.

In a statement explaining the purchase, Kurchenko said: “We are looking for profitable and promising Ukrainian media assets. UMH is one of them. We’re interested in the holding becoming an attractive business asset.”

But many of the journalists who quit or got forced out were uncomfortable working with an owner that their own reporting suggested was close to President Viktor Yanukovych.

One of the nation’s leading media watchdogs says the skepticism is justified. Natalya Ligachova, head of Telekritika in Ukraine, said the purchase of Forbes Ukraine “is a sign that oligarchs are trying to take over everything, and of course they’re tempted by the international formats that have a lot of prestige.” Ligacheva said the potential loss of Forbes as a source of reliable information would remove one of the few remaining independent outlets in Ukraine.

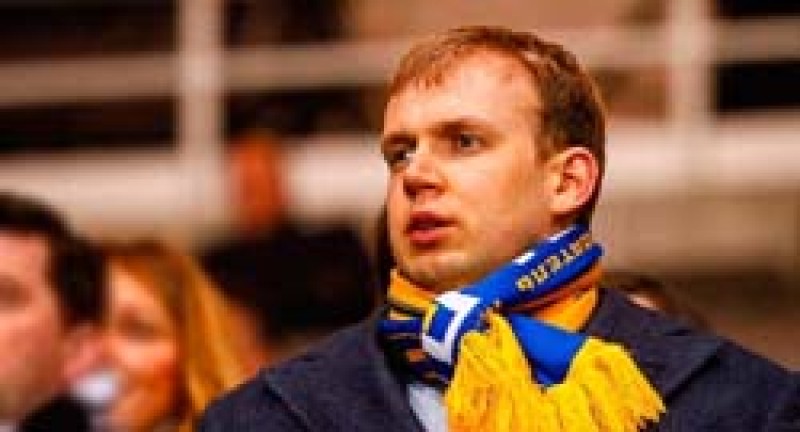

Yaroslavsky’s story Serhiy Kurchenko sits in a skybox at the Metalist stadium in Kharkiv.

Serhiy Kurchenko sits in a skybox at the Metalist stadium in Kharkiv.

Moreover, accusations of bullying tactics have come from Oleksandr Yaroslavsky, another Ukrainian tycoon. When Yaroslavsky sold his Metallist football club to Kurchenko in December, he said that he faced pressure from the local authorities in Kharkiv, Kurchenko’s hometown.

“I was forced to do it,” he told the press at the time of the sale. Asked by a reporter whether there was any chance to settle the conflict with the people who pressured him, Yaroslavsky replied shortly. “Have you seen them? Can you refer to them as people?”

Yaroslavsky is the nation’s 11th richest man, with a fortune estimated by Forbes at $980 million, while Kurchenko doesn’t make the top 100 list, possibly only because his wealth is difficult to track. Yet he has been on a spending spree in the last year, buying an oil refinery, a stadium and a bank in just half a year, among other assets.

Exodus of journalists

When Kurchenko acquired the UMH Group, Fedorin, the then-chief editor of Forbes, released a blockbuster statement:

“I consider the sale of Forbes to be the end of the project in its current form. I am convinced that the buyer pursues one of three aims (or all three at once): to shut the journalists’ mouths before the presidential election, to whitewash his own reputation, and to use the publication to solve problems that have nothing to do with the media business.”

Fedorin announced in June he would quit in October, but ended up getting forced out in July, only a month after his public criticism. While Fedorin described his exodus as amicable, his departure prompted other journalists – including Musaeva and Akymenko – to quit. The new chief editor is Russian Mikhail Kotov.

Forbes undeterred

Representatives of global Forbes said they welcomed the June acquisition as bringing “new opportunity” to Forbes Ukraine.

Moreover, American Miguel Forbes, a fourth generation co-owner and top executive, now advises Kurchenko on “management and development of the media business and external activities” of VETEK, Kurchenko’s recently created holding, according to a statement on the VETEK website.

Forbes declined to answer questions about advising Kurchenko for this article. He oversees business development and the company’s expansion into financial services via the Forbes Family Trust and the Forbes Private Capital Group. “Globally, Forbes’ mission is to seek outstanding business partners with the same values and integrity that Forbes embraces,” the company said in written comments to the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a Kyiv Post partner.

Forbes also maintains that editorial independence remains its primary focus. “Any breach of Forbes’ editorial standards is grounds for termination of the license,” the company said. Forbes attempted to deliver the same messages to Forbes Ukraine journalists at a staff meeting in July, but his effort was described by Fedorin as “pathetic.”

Musaeva called Forbes “the worst motivator imaginable” after he publicly questioned the motives behind the original November investigation into Kurchenko and suggested journalists were victims of rival business interests.

A big prize

There’s little doubt that acquisition of UMH and the Forbes brand is a big prize.

“On the eve of the 2015 campaign we’re seeing a concentration of media resources for those in power,” says Oleksiy Haran, a political sciences professor for Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, a leading Ukrainian university. Haran says that Kurchenko needs the media conglomerate to “advance his business interests and support the political interests before the campaign of 2015.”

In 2012, United Media Holding posted a $16.3 million net profit, making it one of the few profitable media ventures in Ukraine. Part of its success came through a business strategy to venture into the larger Russian-language market, improve its retail network and acquire licenses for famous international brands such as Vogue.

The company’s websites reached half of Ukrainian Internet users, according to the May figures by Gemius, a company specializing in online research in Eastern and Central Europe. Its print titles reach 45 percent of Ukraine’s offline readership, according to MMI Ukraine, a marketing and media index produced by TNS Ukraine, a market research company.

How many of these readers will stay with Forbes, Korrespondent or any of the other popular titles remains to be seen – and may depend on whether the journalists have true editorial independence or become mouthpieces for another rich businessman.