Ведущий одного из подконтрольных Кремлю телеканалов сообщал, что парламент Российской Федерации разрешил президенту Владимиру Путину использовать армию для защиты соотечественников за рубежом. Другими словами, депутаты легализовали аннексию Крыма и создали Путину условия для поддержки вооруженных повстанцев на востоке Украины.

«Я прекрасно помню день, час и секунду, когда принял для себя решение, — рассказывает Манский холодным январским утром в латвийской столице Риге, куда он накануне возвратился после съемок на Украине. — После того сообщения по телевизору вся цепочка последующих событий стала абсолютно ясна. Все, что я предвидел, случилось с точностью до миллисекунды. Это был конец».

Он позвонил своей жене, и они не стали терять времени: «Мы прибыли в Ригу и через три дня уехали из Латвии с видом на жительство в кармане».

На поиск и покупку жилья у них ушел всего день — они стали собственниками квартиры с лепным потолком в центре Риги, заплатив более чем приемлемую по московским меркам цену. Виталий Манский стал одним из 3173 граждан России, кто в прошлом году получил право на проживание в Латвии благодаря программе, которая позволяет иностранцам инвестировать определенную сумму в местную недвижимость и приобрести таким образом вид на жительство.

От Москвы до латвийской столицы около полутора часов лету. Большинство жителей республики говорят по-русски. Но наиболее привлекателен местный закон, по которому собственники жилья получают «постоянную прописку» в Латвии — государстве ЕС. Недвижимость в Латвии недорогая и по карману даже российскому среднему классу.

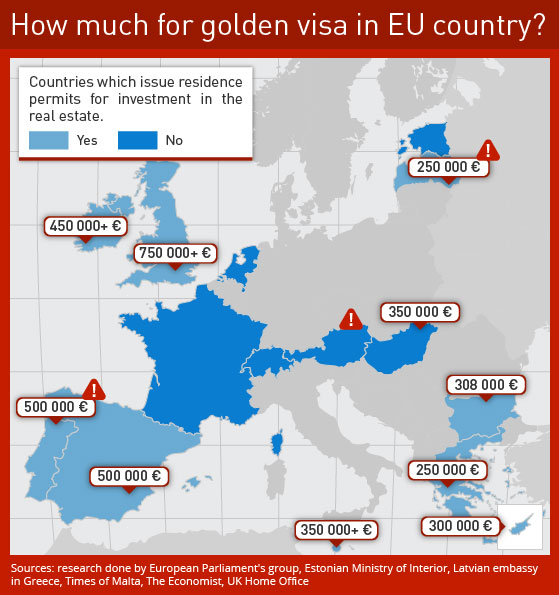

Покупая жилье в Латвии, граждане других стран могут рассчитывать на получение здесь вида на жительство на пять лет, или так называемую золотую визу, которая дает им право свободно перемещаться и жить на территории большинства стран Евросоюза. Сколько именно придется для этого потратить, зависит от того, где находится недвижимость, при этом два «наиболее дорогих» направления одновременно и наиболее популярные.

К примеру, Манскому для покупки квартиры в Риге надо было израсходовать не менее 142 тысяч евро. Такой же минимальный порог установлен и для Юрмалы — курорта на взморье, который жители нынешней России полюбили еще с советских времен. В менее привлекательную недвижимость за пределами этих городов достаточно было вложить всего 70 тысяч евро.

К примеру, Манскому для покупки квартиры в Риге надо было израсходовать не менее 142 тысяч евро. Такой же минимальный порог установлен и для Юрмалы — курорта на взморье, который жители нынешней России полюбили еще с советских времен. В менее привлекательную недвижимость за пределами этих городов достаточно было вложить всего 70 тысяч евро.

За прошедшие пять лет 13 518 иностранцев — население небольшого города — благодаря этому закону получили в Латвии вид на жительство. Еще недавно финансовые условия для этого здесь были самыми «льготными» среди всех стран, где принято подобное законодательство. Однако в отличие от других стран Европы четыре пятых всех претендентов на «золотую визу» были из республик бывшего СССР, в основном граждане России, которым было одобрено 10 тысяч разрешений.

Количество заявок на получение вида на жительство резко выросло после начала массовых акций на Украине в поддержку сближения с Европой в конце 2013 года, а также после фактической аннексии Россией Крыма в 2014 году. В целом за минувший год за долгосрочной визой обратилось вдвое больше жителей Украины, чем годом ранее. Что касается россиян, то массово они стали приобретать вид на жительство после переизбрания Путина в 2012 году, и за прошлый год количество заявок из России оставалось примерно на том же уровне.

Виталий Манский родился на Украине, но большую часть жизни провел в Москве. Он основатель ArtDocFest — фестиваля независимого документального кино, не раз становился лауреатом международных премий. Манский говорит, что отношение к нему российских властей изменилось после того, как он задумал снять документальный фильм о событиях на Украине, взглянув на них через призму истории его собственной семьи.

По словам Манского, его проект первоначально получил одобрение российского Министерства культуры, но вскоре поддержка прекратилась. «Они начали говорить, что с фильмом будут задержки, так как обстановка на Украине нестабильна, и упаси боже, если там окажется наш лучший режиссер. Я понимал, что они лгут», — вспоминает Манский. В конечном итоге сам глава ведомства в беседе с агентством «Интерфакс» предельно прояснил ситуацию: «Пока я министр культуры, ни один проект, к которому имеет отношение Манский, не получит государственной поддержки».

Ответственные лица в латвийской столице признаются, что не знают, сколько из 10 тысяч иммигрантов из России, как и Манский, ищут здесь большей свободы, а сколько среди них преступников, которые таким образом скрывают свои активы или легализуют незаконно нажитые деньги.

Такие вопросы не лишены оснований.

В 2013 году полиция Рима провела обыск в жилище, принадлежащем родственникам беглого казахстанского олигарха Мухтара Аблязова. Аблязов — противник президента Казахстана и человек, выдачи которого по подозрению в финансовых преступлениях добиваются многие страны.

В 2013 году полиция Рима провела обыск в жилище, принадлежащем родственникам беглого казахстанского олигарха Мухтара Аблязова. Аблязов — противник президента Казахстана и человек, выдачи которого по подозрению в финансовых преступлениях добиваются многие страны.

Самому Аблязову тогда удалось избежать встречи с полицией. Позднее он был задержан во Франции, где теперь пытается не допустить своей экстрадиции на родину. Итальянские правоохранители выяснили, что супруга Аблязова и его шестилетняя дочь проживали в этой стране на основании разрешений на долгосрочное пребывание, которые были получены в Латвии и Великобритании.

Наличие вида на жительства давало семье Аблязова право свободно посещать и проживать в любом государстве ЕС — латвийская «золотая виза» открывала им двери всех 26 стран — участниц Шенгенского соглашения. Великобритания в шенгенскую зону не входит, и для нее требовалось отдельное разрешение.

Это дело произвело большой фурор в Италии. Местные власти в итоге депортировали жену и дочь Аблязова в Казахстан, однако позднее им было разрешено вернуться, и в 2014 году они получили в Италии статус беженцев. Мухтар Аблязов остается под арестом во Франции в ожидании экстрадиции.

Средний класс бежит

В течение прошлого года журналисты объединения Re:Baltica — партнера OCCRP в регионе — собрали данные из коммерческих реестров и реестров прав на недвижимость и проанализировали 315 самых крупных сделок по приобретению жилья иностранцами в Риге и Юрмале. Целью было получить общее представление о людях, которые решили воспользоваться программой «золотой визы», а также о том, где они взяли для этого деньги.

В результате выяснилось, что с октября 2013-го по сентябрь 2014 года большинство таких покупателей представляли российский средний класс. Журналисты Re:Baltica отнесли их к категории «от обеспеченных до зажиточных», но не «сверхбогатых» — это, например, предприниматели или управленцы среднего звена.

В результате выяснилось, что с октября 2013-го по сентябрь 2014 года большинство таких покупателей представляли российский средний класс. Журналисты Re:Baltica отнесли их к категории «от обеспеченных до зажиточных», но не «сверхбогатых» — это, например, предприниматели или управленцы среднего звена.

Некоторые из этих людей связаны со средними по масштабу деятельности частными структурами, особенно из финансового сектора. При этом большинство фамилий вряд ли кому-либо известны — возможно, потому, что недвижимость приобреталась на членов семьи, или в силу того, что речь идет о непубличных фигурах.

Также среди покупателей обнаружились журналисты и представители творческих профессий из России. Так, писатель-сатирик и телезнаменитость Михаил Задорнов к своей коллекции недвижимости присоединил квартиру в одном из известных в Риге домов в стиле модерн.

Еще двое покупателей из России стали соседями в Юрмале: актриса Татьяна Догилева и Юрий Аскаров, звезда телевизионного КВН.

Небольшая часть обладателей латвийского вида на жительство — крупные менеджеры российских государственных компаний и их дочерних структур, особенно тех, которые связаны с Газпромом. Например, Николай Коренев — зампредседателя правления «Газпромбанка», попавшего под американские и европейские санкции. Есть здесь и ряд управленцев компании «ТрансТелеком» — «дочки» еще одного государственного гиганта — ОАО «РЖД», шеф которого входит в ближайшее окружение президента Путина.

Видом на жительство обзавелся и Вадим Зингман, заместитель гендиректора по работе с клиентами компании «Аэрофлот». Также в этой группе — один бывший менеджер из банка ВТБ и его (также уже в прошлом) высокопоставленный коллега из «Банка Москвы», или же родственники последних (оба финансовых учреждения в санкционном списке США и ЕС).

Члены семьи Алишера Усманова, который занимает вторую строчку в российском списке Forbes, сделали одно из самых крупных приобретений, заплатив почти 4 миллиона евро за виллу в Юрмале. При этом вид на жительство они не запрашивали (по закону покупатели не обязаны это делать). Официальная владелица недвижимости, жена сына Усманова, не стала отвечать на вопросы журналистов.

Близкий к Кремлю политолог Дмитрий Орлов, член Высшего совета путинской «Единой России», в телефонной беседе в начале февраля отверг утверждения о получении им вида на жительство, однако не стал отрицать, что приобрел в Латвии жилье. В местном реестре прав на недвижимость есть данные о человеке с точно таким же именем и такой же датой рождения. На звонок в дверь фешенебельной квартиры в Риге никто не ответил.

Указанные лица пошли по стопам других, уже бывших депутатов-единороссов, а ныне в большинстве своем бизнесменов, которые купили недвижимость в предыдущие годы и чьи семьи имеют вид на жительство. Это, в частности, Эдуард Янаков — владелец металлургического бизнеса и, предположительно, крупный акционер русскоязычных СМИ в Латвии, и Владимир Шемякин, до недавнего времени один из руководителей «Газпром-Медиа» — структуры, аффилированной с «Газпромбанком».

«Ввиду того, что «Газпромбанк» — негосударственная компания, эта тема для нас неактуальна», — заявили журналистам Re:Baltica в пресс-службе банка. Шемякин и Янаков от комментариев отказались.

Партнер Re:Baltica, телеканал TV3, в эфире расследовательской программы «Ничего личного» сообщил, что близкий друг Владимира Путина, миллиардер Аркадий Ротенберг, был одним из первых, кто в 2010 году получил вид на жительство. Этот документ он, впрочем, не стал продлевать. Право на долгосрочное пребывание Ротенберг получил не через покупку недвижимости, а благодаря вкладу в одном из латвийских банков.

До введения ограничений со стороны ЕС и США Аркадию Ротенбергу и его брату Борису в Латвии принадлежал SMP Bank. Братья Ротенберг считаются людьми, близкими к Путину, и были внесены в санкционный список. После того как санкции начали действовать, собственность Аркадия Ротенберга в Италии была арестована.

Через свою коммерческую структуру Борис Ротенберг владел недвижимостью в тихом фешенебельном районе в Гаркалнском крае неподалеку от Риги. Как обладателю финского гражданства, ему не было необходимости запрашивать вид на жительство в Латвии.

В августе 2014-го Борис Ротенберг перевел свою долю в компании, которой принадлежит дом в Латвии, в собственность своего сына Романа — вице-президента АО «Газпромбанк» и вице-президента хоккейного клуба СКА. Незадолго до введения санкций структура собственности банка была изменена.

Некоторые представители «русской общины» при этом признаются, что решение приобрести собственность в Латвии было сугубо личным и с политикой не связано. «Это то, о чем я давно мечтал. Город очень интересный, и я просто хотел завести здесь гнездышко», — рассказывает покупатель недвижимости из России Александр Рудик, член совета директоров шведской лесозаготовительной компании RusForest, работающей в Восточной Сибири.

«Кроме этого, здесь, в Латвии, привлекательная система корпоративного налогообложения, и я посмотрю — может, есть смысл перевести сюда часть моего бизнеса. Я не задумываюсь над тем, чтобы постоянно жить в Латвии, скорее это просто жилье на лето. Но я буду подавать на вид на жительство, так как это удобно для того, чтобы свободно ездить по Европе», — продолжает Рудик.

Неофициальные, но заслуживающие доверия источники говорят, что среди запрашивающих долгосрочную визу есть люди, связанные с такими компаниями, как Роснефть, Роснефтегаз, Росатом, «ЛУКОЙЛ», Национальная газовая компания, Транснефть и другими, однако журналисты Re:Baltica не смогли найти таких людей при анализе самых дорогостоящих покупок недвижимости за прошлый год. Ряд этих российских компаний был внесен в черный список США и ЕС.

Деньги или безопасность — что важнее?

Пять десятилетий советской оккупации и усилия по русификации республики способствовали снижению процентной доли латышей в Латвии. Произошедшие демографические изменения оставили свои глубокие шрамы: в ходе переписи населения каждый четвертый определяет себя как «русский». Из этих примерно 500 тысяч людей треть (172 тысячи) не имеют латвийского гражданства, и некоторые латыши, обоснованно или нет, сомневаются в их преданности Латвии.

Кто приобретает вид на жительство в Латвии

Недавний наплыв граждан России в Латвию по программе приобретения жилья встревожил националистически настроенных политиков, которые опасаются, что новые жители не захотят стать частью латвийского общества. Эта нервозность усугубляется еще и тем, что Путин использовал «необходимость защиты соотечественников» как повод для вооруженного вторжения на территорию соседей — в Крым, Абхазию, Донбасс и другие регионы.

«Продолжая выдавать долгосрочные визы гражданам Российской Федерации, мы играем в русскую рулетку в буквальном смысле слова», — заявил в латвийском сейме в прошлом году член правоцентристского национального объединения «Всё для Латвии!» Эдвинс Шнуоре.

В мае 2014 года решением сейма минимальный размер инвестиций в недвижимость, необходимый для получения вида на жительство, был увеличен с 70 тысяч до 250 тысяч евро, что вывело республику на один уровень с Грецией, которая среди стран Европы раньше уступала лишь Латвии по требуемому объему инвестиций в собственность.

Введение нового минимального порога в сочетании с колоссальным падением курса рубля привело к резкому сокращению числа покупок недвижимости. В период между сентябрем 2014 года, когда был изменен соответствующий закон, и концом января 2015 года было подано лишь 67 заявок на получение вида на жительство.

Однако на фоне стремительного замедления латвийской экономики лоббисты, представляющие интересы индустрии недвижимости, возобновили борьбу с целью вернуть условия для этого прибыльного бизнеса. Так, один из депутатов сейма от правящей партии «Единство» внес законопроект, который серьезно опускает минимальный порог инвестиций в недвижимость даже ниже существовавшего уровня: минимум должен составить 50 тысяч евро не за один, а за три объекта собственности за пределами Риги.

Лоббисты, за которыми стоят крупные бизнесмены, девелоперы и банкиры и их клиенты (в основном из республик бывшего СССР), указывают на то, что с начала кризиса застройщики начали ориентироваться на покупателей из-за границы. Лоббист Викторс Валайнис, в прошлом член парламента, говорит, что, если новые проекты застопорятся, то под угрозой окажутся инвестиции в размере 200 миллионов евро, а также 5500 рабочих мест в строительной и смежных отраслях.

Такая позиция встречает жесткое неприятие спецслужб страны, а также участников правящей коалиции, представляющих националистическое крыло, в частности министра обороны Раймондса Вейониса из Союза зеленых и крестьян.

В силовых структурах заявляют, что опасаются не столько наплыва грязных денег или деятелей из криминальных кругов, сколько возможности того, что из-за большого количества заявок они не смогут отсеять тех, кто представляет угрозу для государства. «С принятием нынешнего закона потенциальные риски снизились, — говорит шеф Полиции безопасности Нормунд Межвиетс. — И с точки зрения интересов национальной безопасности я не вижу необходимости в каких-либо изменениях».

Тем временем кинорежиссер Виталий Манский продолжает работать над своим фильмом при участии партнеров из Латвии. О последней волне приехавших из России он говорит: «У каждого свои причины. Возможно, есть и такие, которые бегут из России, но Рига в этом смысле не самое безопасное место — ни идеологически, ни географически».

По словам Манского, продолжающаяся война на Украине — зримое напоминание о том, что ситуация способна ухудшиться в одночасье. «В стране, настолько зависимой от воли одного человека, может произойти все что угодно», — заключает режиссер.

В создании этого репортажа приняли участие Илзе Яуналксне (Рига) и Елена Логинова (Киев)