Reported by

A provision buried deep in a U.S. tax mega-bill threatens to weaken years of efforts to reduce the flow of money through informal networks linked to drug cartels and terrorism supporters, critics said.

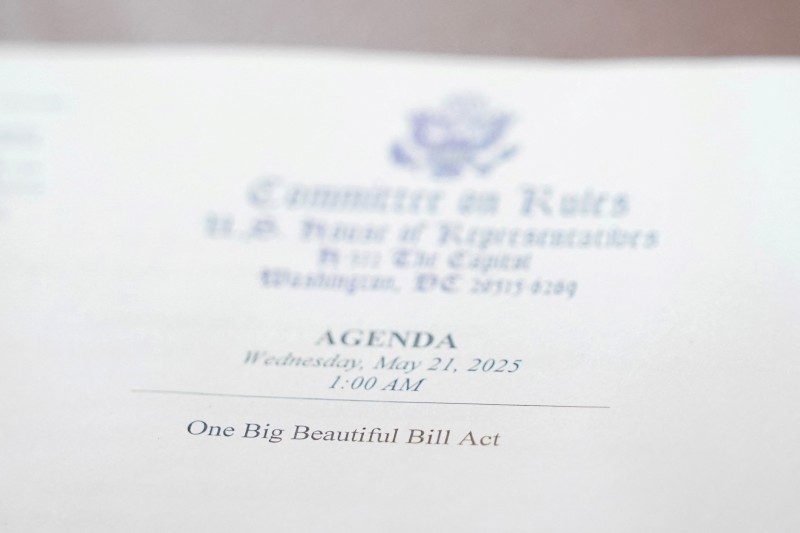

The U.S. Congress and Senate passed sweeping tax legislation dubbed the One Big Beautiful Bill, which extended expiring tax cuts, added news ones and slashed spending on America’s social safety net.

Among the lesser known changes in the bill is a provision slapping an excise tax equal to 1 percent of the money being transmitted abroad by immigrants in the U.S.

The tax will be collected by money-transfer companies, such as Western Union and MoneyGram, which will send it to the government on a quarterly basis.

Critics warn that the provision is likely to incentivize some immigrants to avoid using licensed money transfer companies, according to Julia Yansura from the FACT Coalition, an alliance of organizations promoting financial transparency.

Instead, she added, people may avoid the tax by transferring money through informal networks — which are often tainted by association with organized crime.

"While Congress’ remittance tax raises relatively little money for the United States, these paltry funds will come with a huge illicit finance risk, driving financial flows underground,” Yansura told OCCRP.

Her concern that migrants would simply tap into informal networks like those that help drug cartels launder money is one shared by several FinTech and electronic payment groups too.

In the run-up to the vote on the new bill, the Financial Technology Association and six other trade groups warned that the proposal would make it “harder to combat transnational crime by pushing cross-border payments into unregulated channels.”

World Bank researchers estimated that in 2023 — the last year for which there was complete data — roughly $656 billion in remittances flowed to low and middle-income countries from more developed nations like the U.S., Canada and members of the European Union.

The September 11, 2001, attacks by al Qaeda on the U.S. led to international standards-setting bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force, and other efforts to bring remittances into the regulated system. Extremist groups often use an informal cash transfer business, centuries old and known as “hawala,” to move money outside of traditional banks.

The U.S. Treasury Department and law enforcement have for more than two decades worked to close down informal money transfer operations used by drug cartels. The Treasury Department did not respond to a request for comment on the new legislation.