Since Russia launched its brutal invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, condemnation of Vladimir Putin’s overseas aggression has reached a fever pitch. Yet Russia can still rely on the occasional friendly voice in Europe: Last November, for example, far-right Italian local legislator Stefano Valdegamberi penned an op-ed decrying the EU’s decision to designate Russia a terrorist state as “a serious mistake” that “foments conflict by denying historical truth.”

But what Valdegamberi didn’t mention was that he had long been collaborating with a secretive Russian lobbying group with a direct link to the Kremlin. Since at least 2014, that group had designed plans to channel cash to European politicians to help it legitimize Russia’s occupation of Crimea and promote pro-Moscow policies inside EU countries.

Details of the group’s activities have come to light via hacked and leaked emails belonging to its coordinator, Russian parliamentary staffer Sargis Mirzakhanian, who ran the “International Agency for Current Policy” in the years following the annexation of Crimea.

The emails suggest his group paid politicians thousands of euros to put forward pro-Russian resolutions in European legislatures, a new investigation by Eesti Ekspress, in partnership with OCCRP, IrpiMedia, iStories, and Profil, has found.

It also helped arrange for political figures from countries including Germany, Austria, Italy, the Czech Republic and Poland to be flown on expensive junkets to pro-Russia events in occupied Crimea, and paid honoraria for their presence.

The lobbying group also flew several European political figures to Russia to act as official election observers.

The emails, which were leaked by a group of Ukrainian hacktivists, reveal especially close ties between Mirzakhanian's operation and officials in Italy and Cyprus. These ties paved the way for pro-Russian motions to be passed in both countries, with both the Cypriot parliament and multiple Italian regional councils calling for an end to sanctions against Russia over its invasion of Crimea.

Previous media reports have shown links between EU politicians and Kremlin propagandists, but this is the first comprehensive insight into how this campaign was run from Russia. The emails show that Mirzakhanian, a well-connected staffer and adviser in Russia's parliament, the Duma, built a network of political analysts, journalists, activists, and academics who helped him push the Kremlin’s interests abroad.

Anton Shekhovtsov, chair of the pro-democracy non-profit Centre for Democratic Integrity, said the leaked emails “represent one of the most important sources of our knowledge of how particular engines of the Russian political war machine works.”

Most significantly, Shekhovtsov said, they showed Mirzakhanian's role coordinating protests, placing media articles, and preparing parliamentary resolutions across Europe, while organizing “fake” election observation missions as he and his associates sought to legitimize the annexation of Crimea and “advance Russian domestic and foreign policy interests.”

The emails run from March 2007 until September 2017, and it’s unclear whether the International Agency for Current Policy is still at work today, although those linked to the network like Valdegamberi continue to make pro-Russian statements.

Olga Lautman, a researcher on Kremlin-related disinformation and hybrid threats at the Center for European Policy Analysis, said that groups like Mirzakhanian's had helped open the door to Russia’s ongoing aggression in the rest of Ukraine.

“Russia was extremely successful in its efforts to soften the response to its various campaigns by putting former and current politicians on its payroll,” she said.

“Russia’s latest full-scale invasion is a direct result of the international community's failure to hold Russia accountable after the 2008 Georgia invasion, the 2014 Ukraine invasion, the atrocities they helped [Bashar al-] Assad commit in Syria, and the various assassinations or attempts, using chemical weapons on foreign soil.”

Mirzakhanyan and other key figures connected to his group did not respond to requests for comment.

‘The Price Tag of the Vote’

The International Agency for Current Policy is described in one PowerPoint presentation found within the leaked emails as a “closed association of professionals" that aimed to “cooperate with leading EU parliamentary parties and individual politicians.” Other presentations and draft presentations named Austria, Germany, Italy, Bulgaria, Greece, Cyprus, Latvia, Romania and Turkey as target countries.

The organization appeared to have a direct link to the Kremlin: Mirzakhanyan exchanged more than 1,000 emails between 2014 and 2017 with Inal Ardzinba, a department head in the Russian presidential administration who worked under Vladislav Surkov, a key adviser to President Vladimir Putin at the time.

The activities of the International Agency for Current Policy are made clear in a series of presentations attached to emails in the leak, as well as details in the emails themselves. They ranged from organizing anti-NATO street protests to peddling influence with European lawmakers.

The documents also discuss bringing European delegations to Moscow and Crimea, and targeting “national parliaments of the EU” with pro-Russian resolutions. The latter included resolutions to end anti-Russian sanctions and recognize Russia’s claim to Crimea.

The emails show how Mirzakhanian's group arranged to make considerable payments to ensure that EU politicians pushed favorable motions in their home countries. Mirzakhanyan bluntly described these payments as the “price tag of the vote” in an email that contained project outlines for Italy and Austria.

The group planned for Italian Senator Paolo Tosato and Austrian Member of Parliament Johannes Hübner, both from far-right parties, to put forward resolutions in their respective legislatures to lift sanctions against Russia. The project outlines don’t go into detail about how this would happen, but a “budget” of 20,000 euros was listed for both the Italian and Austrian resolutions, with a further 15,000 euros for each “in case of successful voting.” It’s unclear whether these sums were intended to be paid directly to the two politicians or were budgets for the entire projects.

In the end, Hübner and Tosato both presented resolutions against Russian sanctions on their respective parliament floors, but legislators did not adopt them. (These project plans were reported in the media last year, but without identifying the role played by Mirzakhanian's organization. Tosato denied receiving payments from Russia for the resolution, as did Hübner’s party, FPÖ.)

Mirzakhanian: The Missing Link

The leaked Mirzakhanian emails were first obtained by Ukrainian hacktivists in 2020 and have been reported on before, but the extent of Mirzakhanian’s coordinated campaign to influence European politicians and push Moscow’s agenda across the EU has never before been revealed.

The documents also detail separate projects for Latvia, Greece, and even the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). However, there are no indications that these motions were ever proposed.

That doesn’t mean the International Agency for Current Policy didn’t find any success, however. In both regional councils in Italy and the national parliament of Cyprus, motions drafted with the help of Mirzakhanian's Kremlin-linked apparatus were actually passed.

Success Stories

“It’s a bomb! From the point of view of the media, this will most likely be our loudest informational operation,” wrote Mirzakhanyan to a colleague in April 2016.

The International Agency for Current Policy was on the brink of its first significant European success: A local council in Veneto, Italy, was preparing a motion recognizing the results of rigged Russian referendums in Crimea and calling for the end of EU sanctions against Russia.

The motion had been drafted with the help of Mirzakhanian's group, and their inside man was the local councilor Valdegamberi, at that time associated with the far-right Lega Nord party.

On May 18, 2016, the resolution was adopted in the council by a majority vote. Although a regional legislature has no meaningful power over state policy, numerous Russian propaganda media outlets gleefully reported on the first region in the EU to give legitimacy to Crimea’s annexation. In following months, led by the Lega Nord party, Italian local councils in Liguria and Lombardy followed Veneto's example and passed their own resolutions “recognizing” Crimea as part of Russia.

“It is extremely important for Russia to infiltrate countries on every level, including local municipalities,” said Kremlin expert Lautman. “Russia would use these resolutions for domestic propaganda purposes and to infiltrate local municipalities to influence local opinion and capture local politicians.”

A few months after the Veneto motion, the group achieved an even more significant victory, this time in Cyprus.

In late April 2016, Mirzakhanian’s aide Areg Agasaryan sent him another project idea, suggesting a motion to be proposed to the Cypriot parliament by Andros Kyprianou, the longtime general secretary of Cyprus’s Progressive Party of Working People.

Agasaryan, who like Mirzakhanian is a graduate of Russia’s diplomatic academy, had made contacts in Cyprus via Dmitry Kozlov, a Cypriot-Russian businessman who put the group in touch with pro-Russia politicians there.

The motion presented by Kyprianou’s party in July 2016 matched those drafted by Agasaryan or his colleagues, and included two additional demands: Lifting sanctions against individual Russians, and implementing the terms of the February 2015 Minsk agreements between pro-Russian forces and Ukraine.

The motion was passed, putting the Cypriot parliament at loggerheads with the EU’s own position on sanctions against Russia over the Crimea annexation.

In October 2016, Kyprianou was invited to a meeting in Moscow with Kozlov and two leading figures promoting investment in Crimea, Andrey Nazarov and Rustam Muratov.

The latter pair’s organization Business Russia played a key role, alongside the International Agency for Current Policy, in pushing for Europe to accept Russia’s occupation of Crimea. Central to that effort were Russian state-funded trips for European politicians to an annual conference at a luxury hotel in Yalta, Crimea.

Kozlov told OCCRP he knew Agasaryan “from university years” and that he had been involved in the pro-Russia motion in Cyprus, but didn’t comment on the meeting in Moscow. Kyprianou told OCCRP that Kozlov had pressured him to meet Nazarov in Moscow, and said he had been unaware that the resolution on Russia was coordinated by Mirzakhanian’s team. Nazarov and Muratov did not respond to requests for comment.

Crimean Junkets

In several cases, the establishment of cooperation between European politicians and the Kremlin can be traced back to the Yalta International Economic Forums, organized with the help of Mirzakhanyan and his group. Business Russia’s Muratov and Nazarov were also executives at the forum, which the U.S. Treasury Department described as "the main Russian platform for showcasing investment opportunities in Crimea."

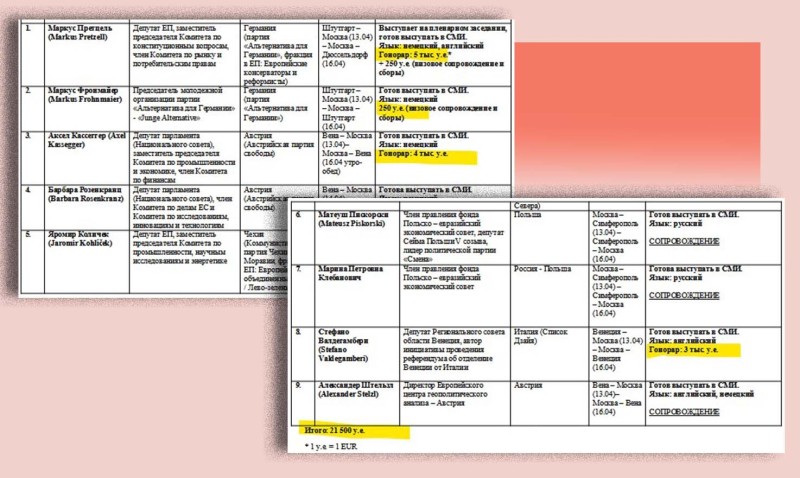

In April 2016, Mirzakhanyan sent Muratov a document entitled “European estimates,” which listed nine European politicians from Austria, Germany, Italy, the Czech Republic, and Poland who would attend the Yalta forum, along with a total of 21,500 euros’ worth of “honoraria” broken down by politician. These fees appear to go beyond compensation for expenses, since travel costs for each attendee were discussed in separate email exchanges. Another set of emails reveal how the organizers bought tickets worth around 7,600 euros to fly in the nine political figures.

Marcus Pretzell, a former member of the European Parliament from Germany, whose name was listed in the document, denied being offered any money for his presence at the Yalta forum.

“I was offered membership on the board of the forum, which I rejected,” he told OCCRP.

Current member of the Austrian parliament Axel Kassegger and former politician Barbara Rosenkranz, both affiliated with the right-wing Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ), are also named in the “European estimates” document. They told OCCRP they did not receive payments either.

The purchase of the flights was organized by a marketing director from Granel, a major Russian construction company co-founded and chaired by the Yalta forum executive Nazarov.

The organizers also funded the politicians’ accommodation at the five-star Mriya Resort and Spa, a $300-million hotel on the shores of the Black Sea. The Russian government and a mix of state-backed and private banks sponsored the event, according to the Yalta forum’s website, and the state-owned Sberbank financed the construction of the hotel, which would later be sanctioned by the U.S. for its role as host.

“It is important for Russia to have Western politicians visit…Crimea, in order to normalize and whitewash their illegal invasion and occupation,” Lautman said. “Domestically, [Russia] uses these visits for propaganda to show that Europe not only accepts the annexation of Crimea but there is nothing illegal [about] this aggression.”

“Russia wins in its PR operations every single time a politician or any influential figure visits Moscow or Crimea,” Lautman added.

From the outset, Ukraine protested the attendance of European politicians at the Yalta forums, but more and more of them continued to visit in 2017, 2018, and 2019 (the subsequent events were canceled due to the pandemic).

Observers Doing Business

Among the correspondence between Mirzakhanyan and Russian politicians are emails from Leonid Slutsky, a longtime member of Russia’s Duma aligned with the Kremlin, who chairs the committee on International Affairs. An exchange from 2017 reveals how Mirzakhanian's and Slutsky’s teams worked together to bring prominent Europeans to observe local elections in Russia, covering their travel and accommodation costs.

The invitations were arranged through an NGO that Slutsky led, Russian Peace Foundation, and the 2017 election observation project had a budget of at least 68,000 euros, according to the leaked emails. Three members of the European Parliament and several local parliamentarians from countries like Belgium and Sweden were flown in for the occasion.

“Fake election observation is often an entry door to other pro-Kremlin activities which then might end up also in financial relationships or corruption,” said Stefanie Schiffer, chair of the board of European Platform for Democratic Elections, an organization that tracks election observation missions in Russia and elsewhere.

The code of conduct for international election observers says they should not “accept funding or infrastructural support from the government whose elections are being observed, as it may raise a significant conflict of interest and undermine confidence in the integrity of the mission’s findings.”

Schiffer said the 2017 mission “contradicted this requirement.”

Other politicians with ties to Mirzakhanian's International Agency for Current Policy observed more recent Russian elections. For example, the Italian councilor Valdegamberi attended the Russian presidential election in annexed Crimea in 2018 and was also an election observer at the 2021 Russian parliamentary elections.

"I was struck by the transparency of everything," he told Russian media during the 2021 vote.

Earlier emails show how Valdegamberia had seemingly sought to monetize his Kremlin connections. After the 2016 Yalta forum, he flew to Crimea seeking business relationships and brought other Italian politicians with him: Three from the Veneto region, plus one each from Tuscany, Lombardy, Emilia Romagna and Liguria. A delegation of Italian investors joined the trip.

“For Stefano [Valdegamberi] the result of the trip was not purely PR, but the organization of promising contacts for business ventures, which pay for his election campaigns and support his political viability,” wrote one of Mirzakhanian's European associates in an email to him in October 2016, just after the delegation’s visit to Crimea.

The strategy bore some fruit: The Chairman of the State Council of the so-called “Republic of Crimea” signed a cooperation agreement with the president of the Veneto regional council promising to build economic ties, and Russian state media announced various business deals established between Italian industrialists and Crimea.

Valdegamberi did not respond to reporters’ questions.

Key Allies in Austria, Germany and Poland

The leaked emails show how four specific political figures in Europe worked especially closely with Mirzakhanyan and his group: Robert Stelzl, a pro-Russia political activist from Austria; Manuel Ochsenreiter of Germany’s populist right-wing AfD party; Mateusz Piskorski, a Polish political activist arrested in 2016 for spying for Russia; and Piskorski’s wife, Marina Klebanovich, who helped coordinate the Agency’s activities in Europe.

Stelzl had worked for Piskorki’s think tank, The European Center for Geopolitical Analysis, and it was through Piskorski that Stelzl was invited to the 2016 Yalta forum. Emails show him setting up a call with Mirzakhanyan that led to a close working relationship: They subsequently exchanged more than 90 emails. These indicate Stelzl was paid for publishing Kremlin-coordinated articles in the Swiss magazine Zeit-Fragen.

In an email exchange from September 23, 2016, Stelzl complained to Klebanovich about the quality of an article he was being asked to sign.

“As it will be paid, Sargis doesn’t want explanations, but wants to get a text,” she told him.

“If he wants to get the message printed he has to accept that it must be of a style and contents that is acceptable,” he responded, adding: “I am not a robot.”

Four days later, an article by Stelzl ran in the magazine praising Russia’s most recent Duma elections as transparent, open and legitimate.

Stelzl had also set up and joined the Italian delegation to Crimea led by Valdegamberi in October 2016, and seems to have acted as an intermediary between the Russian propagandists and European politicians.

Stelzl had worked for Austrian MEP Ewald Stadler, a former member of the FPÖ party, which was a key ally of the International Agency for Current Policy. FPÖ members joined the Italians on their 2016 trip to occupied Crimea and were regular attendees at the Yalta forums. The Yalta forum even held a gala event in Vienna in 2018. The year before the gala, Mirzakhanian’s group arranged for a 25-strong FPÖ delegation to visit Moscow.

Stelzl told reporters he had fully supported Russia “for decades…and now even more than ever,” but would not respond to specific questions.

In Germany, Ochsenreiter demanded thousands of euros to publish pro-Russia articles orchestrated by Mirzakhanian's associates in the magazine he edited, ZUERST!. Emails show this propaganda campaign had a budget of 12,000 euros, and included plans for an interview with AfD’s Marcus Pretzell on the problems with Russian sanctions, which was published in July 2016.

As with FPÖ in Austria, AfD was a key ally for the International Agency for Current Policy. Mirzakhanian’s emails include a plan to fund the 2017 political campaign of AfD’s Markus Frohnmaier, and show how in March 2016 the network worked on a draft of AfD's anti-sanctions resolution, which was submitted at the legislative assembly of Baden-Wüttenberg two months later.

Ocshenreiter was later investigated for drumming up hatred between Ukraine and Hungary via false-flag arson attacks against a Hungarian center in Ukraine, but fled to Moscow and died there suddenly in 2021.

Piskorski was apprehended in Poland in May 2016, two months before a NATO summit in Warsaw. Emails show Mirzakhanian had planned a massive pro-Russian influence-peddling operation for the event with the help of Piskorski’s party, Smena. Piskorski was charged with carrying out espionage for Russian and Chinese intelligence, and though he was released on bail in 2019 he remains under police supervision. (Piskorski and Klebanovich did not respond to requests to comment).

Documents setting out Piskorski and Mirzakhanian’s plan, which aimed to promote anti-NATO stances in various countries during the Warsaw summit, included the names of a journalist and four political figures they were working with. In 2021 two of them — Lithuanian Algirdas Paleckis and Hungarian Béla Kovács — were found guilty of spying for Russia.

While Mirzakhanian has disappeared from the public eye, his group’s allies in Europe continue to make pro-Moscow statements and agitate for Russian interests: AfD’s Frohnmaier has criticized Germany for helping Ukraine; FPÖ’s Axel Kassegger demanded in September last year that Austria review its stance on Russian sanctions; and Robert Stelzl was photographed at a pro-Russian rally in Vienna in November wearing a t-shirt sporting the infamous Russian “Z” symbol and the text “Russian Army.”

Asked by reporters about the photo, Stelzl was unapologetic: “I bought this from Serbia. It is of good quality, breathable and the message is right.”

Stefan Melichar (Profil) and Dmitry Velikovsky (iStories) contributed reporting.