Reported by

Nurhayati Jumadi, a villager on the Indonesian island of Obi, still remembers the cashew grove her grandfather kept by a nearby spring. He never brought water when he went to tend it, she said — he simply drank straight from the river.

Today, that river runs thick with reddish-brown sediment. Not far from Jumadi’s small wood house in the village of Kawasi, a sprawling nickel mine owned by Harita Group, a major Indonesian conglomerate, turns up hundreds of thousands of tons of ocher soil a year. A nearby smelting plant belches smoke into the air.

Since mining started, Jumadi said, she has begun to cough pus and blood. Like many of the other villagers, she said she still drinks from Kawasi’s spring — and often suffers stomach cramps and diarrhea.

“We don’t know if it’s the water. But we drink it every day,” she said.

Nurhayati Jumadi, a villager on Obi Island, Indonesia

Harita Group is a major global producer of nickel, a key component in electric car batteries and stainless steel. Over the past two years, the company provided about 6 percent of the world’s supply of the mineral, according to company and U.S. government figures. It also has holdings in sectors as diverse as palm oil, coal, and timber.

Harita’s operations on Obi, which opened in 2010, were branded a hallmark economic project for Indonesia and have been legally required to undergo regular environmental testing. It has even won national awards for sustainable practices. But in recent years, concerns about its impact have mounted.

Obi Island in Indonesia.

In February 2022, the Guardian reported that Kawasi’s drinking water contained high levels of hexavalent chromium, a toxic chemical also known as chromium-6. Chromium-6 was the chemical pollutant portrayed in the film “Erin Brockovich,” which told the story of a California woman fighting to save her town from the effects of groundwater contamination. It has been shown to cause serious health problems in people exposed to it, including liver and kidney damage, respiratory cancer, and skin ulceration.

Harita Group has denied the Guardian’s findings and sought to downplay the nickel operation’s environmental impact. But behind the scenes, the conglomerate’s internal discussions have been very different from its public stances, an investigation by OCCRP, The Gecko Project, The Guardian, KCIJ Newstapa, and Deutsche Welle has found.

For a decade, Harita Group’s own internal monitoring repeatedly found chromium-6 contaminating the waters around Kawasi, hundreds of leaked company emails, testing records, and other documents show. Data collected just two days before the Guardian story was published showed that chromium-6 levels were well above the legal limit at that time.

Sediment displaced into the Akelamo River in Kawasi, Obi Island, Indonesia.

Company officials repeatedly acknowledged in the leaked correspondence that Harita’s operations were the cause of the contamination. Some executives clearly recognized the need to get the pollution under control. But they also fretted about government officials clamping down on them, and expressed concern that NGOs might pick up on chemical readings as they spiked far above legal levels.

Harita implemented a series of measures to control the pollution, including installing ponds to collect toxic runoff and carrying out chemical treatments. But although the data did show chromium-6 levels falling within legal limits in some instances, many other readings exceeded them for years — sometimes by as much as three times.

Meanwhile, the group continued to mine for nickel and launched a processing plant to produce battery-grade nickel for the electric vehicle market just 200 meters from Kawasi’s spring. It also listed shares of its nickel subsidiary on Indonesia’s stock exchange in 2023, netting hundreds of millions of dollars even as its data showed chromium-6 levels remaining stubbornly high in the months before the offer.

About the Harita Group Leak

Three villagers interviewed by a reporter who visited Obi island said they still bathe, cook, and drink with water from the spring. Another eight said they use it to bathe and cook but no longer drink from it. None of those interviewed said they received any warning about water contamination.

“There was no notification from the company,” Jumadi said. “Especially not to inform us that, ‘Residents, our water has been polluted.’ There was none at all.”

Mann Noho, a local resident who once worked for Harita, said the spring water's taste was strange, and the color was off. His four children suffer from relentless stomach aches, he said.

“For those who have money, they buy bottled water. For people like me, we have no choice but to use that water,” Noho added.

Credit: Rifki Anwar/The Gecko Project

Mann Noho, a villager who uses the local water supply.

Reporters asked five experts to review Harita’s testing data from the Obi spring, which was found in the leaked documents. They all said the evidence showed chromium-6 levels had exceeded World Health Organization guidelines and posed a risk to public health.

After reviewing reporters' findings, Laode M. Syarif, a lead environmental law trainer at Indonesia’s Supreme Court, and a former commissioner of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission, said the newly uncovered internal documents could form the basis for administrative, civil, or even criminal prosecution.

“Activists and journalists have long reported water pollution from nickel mines,” he said. “But this — internal company data — proves violations of Indonesian environmental law.”

The leaked correspondence doesn’t show what data Harita submitted to authorities or what action the government took in response. But the company has often quoted environmental officials as saying its operation adhered to regulations. One January 2023 statement, for instance, quoted an investigator for a local environmental agency as saying the nickel mining subsidiary “has proven its compliance.”

The Environment Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment. The Harita Group, its nickel mining subsidiary, and the individual executives mentioned in the correspondence also did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In the days after the requests were sent, however, the conglomerate did put out multiple press releases and a video highlighting its environmental compliance and stressing that Kawasi’s spring water was safe to drink.

A Kawasi villager creating a makeshift water tap on Obi Island, Indonesia.

Harita Arrives in Obi — And Chromium-6 Levels Spike

The island of Obi lies about 1,400 miles east of Indonesia’s capital, Jakarta, in the Maluku Sea in the Pacific Ocean. Known for its nutmeg and cloves, Obi was once a waypoint on the global spice trade route.

More recently, the island’s nickel deposits have drawn international attention — particularly with growing demand for electric vehicles, whose lithium-ion batteries rely heavily on the mineral.

Obi marked the first major foray into the nickel business for Harita Group, a vast conglomerate owned by 96-year-old billionaire Lim Hariyanto Wijaya Sarwono and his family. In 2010, the company started mining the mineral on the island through a subsidiary, PT Trimegah Bangun Persada, known by its initials PT TBP.

The company set up its operation on land surrounding Kawasi, a village on the island’s west coast. Workers flooded in, drawn by jobs in the mines and processing plants.

Nickel mining is a destructive process. Its open-pit mines strip away swaths of forest and soil, and runoff leaves nearby waters churning thick with brown sediment and toxic chemicals such as lead and cadmium.

The operations also employ high-temperature extraction methods to separate nickel from water — a process that transforms chromium into its more toxic form, chromium-6.

Harita Group’s Obi Island mining operations on land around Kawasi, Indonesia.

Indonesian law requires mining companies to mitigate potential environmental damage by monitoring wastewater and groundwater and report their findings to authorities. With regard to chromium, including chromium-6, drinking water cannot contain more than 50 parts per billion of the pollutant, while wastewater cannot exceed 100 parts per billion.

When higher levels are recorded, companies face heightened scrutiny from authorities and must show they are taking action. If they don’t, they could face penalties ranging from fines to having the business shut down — or potentially even criminal prosecution.

The levels of chromium-6 in water running off one of Harita’s mines was three times the legal limits as early as 2012, the leaked documents show. A monitoring report from that year shows that wastewater samples taken from two points showed chromium-6 concentrations of 350 and 130 parts per billion — both well above the threshold.

By at least 2013, Harita had started trying to reduce pollution levels by building “sediment ponds” — shallow basins designed to trap contaminated water and stop it flowing out, the leaked emails show. The company also began dosing its wastewater with ferrous sulfate and made use of wetlands to absorb contamination. (The leaked communications do not show what action, if any, was taken before this time.)

But the internal testing showed that these efforts failed to prevent chromium-6 levels from continuing to exceed legal limits.

Executives at the highest level of the company were made aware of these breaches. In October 2013, Harita’s director and head of health, safety, and environment, Tonny Gultom, wrote to four Harita managers, including Chief Operating Officer Shaun Lim, noting the need to identify the area contributing to high chromium-6 levels and develop a system to manage runoff.

Lim responded that he was “okay with this,” though the emails do not show what action was taken as a result. Gultom and Lim did not respond to requests for comment.

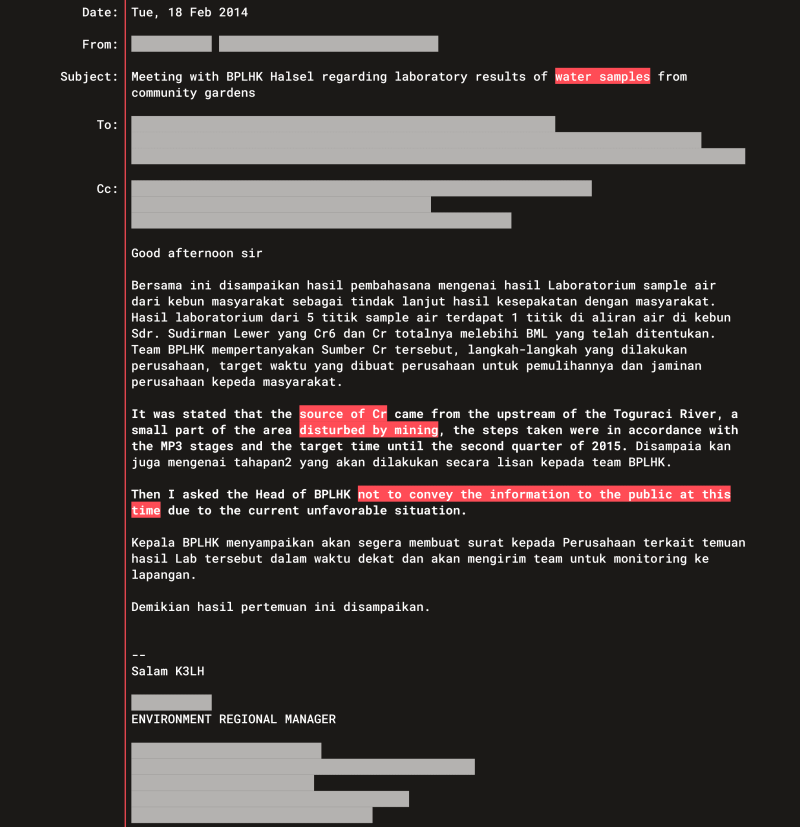

A few months later, in February 2014, an environmental regional manager wrote to Gultom and seven other Harita employees about the persistently high levels of chromium-6 in the samples, and said he had asked an Environment Ministry official “not to convey the information to the community at this time.”

An email from a Harita environmental regional manager to the group’s director and head of health, safety, and environment Tonny Gultom.

A few days later, Gultom urged staff to “make a higher effort” to bring chromium-6 levels down, writing that “I still see too many non-compliant values from this chromium-6 at all compliance points.”

Gultom worried that the chromium-6 levels could cause the project to “go black,” a reference to the country’s lowest environmental performance rating. Companies with this rating face penalties including fines, legal prosecution, or even shutdowns. He added that he hoped that accelerating the construction of sediment ponds would “be able to help a lot.”

One co-worker thanked him for the information, and said he would check with a colleague about why it wasn’t reported earlier. The emails do not show specifically what happened in response to the findings.

In any case, the problem persisted. In October 2016, Gultom sent an email to Harita Group’s environmental compliance staff that included a report from a company geologist detailing chromium’s presence in Kawasi’s nickel deposits — and how mining could convert it into its more toxic chromium-6 form.

The report outlined how chromium-6 dissolves in water, penetrates cell membranes, and accumulates in the body. Exposure, it warned, could lead to skin irritation, gastric issues, and lung cancer, as well as affect fetal development.

“This is why we need to seriously tackle the Cr6 [chromium-6] problem,” Gultom wrote.

One executive forwarded the email to various colleagues, saying that he intended to find a “comprehensive solution” to the chromium-6 problem by the first quarter of the following year.

The communications do not make clear specifically what action was taken, but the internal readings continued to show chromium-6 levels breaching legal limits for years after.

Credit: Rifki Anwar

An aerial view of Obi Island, Indonesia.

Risk of Being Placed on ‘Red List’

The emails make clear executives knew the mine was the source of the pollutant.

In April 2017, testing data showed that chromium-6 levels in the river near Kawasi were still regularly high. Gultom forwarded the data to a group of colleagues, writing that the “source of the increase” was “the active mining and the flow from the factory.”

One, in turn, forwarded it on to another manager, prefacing the email with a note of caution in English: “For your eyes only.” The emails did not include any further replies or make clear if any specific action was taken in response.

In October 2018, Gultom emailed PT TBP’s general manager at the time, Younsel Roos, to warn that if contamination results were reported to the Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Harita could face heightened scrutiny.

"If we report this … we will be included in the red list of companies that will be supervised," Gultom wrote. "Please help us, sir, so that we can discuss this in the field and how to manage this mine water.”

Roos did not reply to requests for comment.

The “red list” is a designation by Indonesia’s environmental authorities that could result in increased scrutiny. Roos forwarded the message to five colleagues, writing, “Here is some information from Mr. Tonny for us to think about and follow up on.” (It’s not clear what action, if any, was taken.)

Later emails show Gultom expressing concern that activists might be able to pick up on the rising levels of pollutants. In a July 2018 email referring to “high values of total Cr [chromium] and Cr6 [chromium-6]” that had been detected, he wrote that he was “worried that if there are NGOs taking water samples downstream, the two parameters above will be easily detected.”

Though multiple colleagues forwarded the email with the message, “FYI,” to other colleagues, the leaked emails do not show if there was any further response.

Harita Expands Into Nickel Refining

In 2018, Harita expanded its Obi operations, breaking ground on a refinery that used a specialized process known as “high pressure acid leaching,” or HPAL, to turn low-grade laterite nickel into the high-purity material needed for EV batteries.

The plant, Halmahera Persada Lygend, was a $1 billion joint venture with Chinese metals giant Lygend Resources & Technology Co., Ltd. Gultom was appointed its director.

The industrial complex began to sprawl. Satellite images hint at the impact on Kawasi: In 2018, the closest industrial structure to the village was about a mile away, but by 2021, the year the plant came online, the complex had crept to within 200 meters of the spring that provided the village’s drinking water.

The joint venture paid off. Harita Group secured deals to supply refined nickel to Chinese battery manufacturers, which, in turn provided components to suppliers of major electric vehicle makers such as Tesla, BMW, Ford, Volkswagen, Mercedes Benz, and others.

Automakers Respond

Within a year of the facility opening, it generated $1 billion in revenue. The chromium-6 issue, however, persisted — and internal correspondence suggested the refinery might be adding to the problem.

“Cr6+ [chromium-6] has been high in the past due to the influence of the Slag stockpile area, mine yard area and now the HPAL project opening area,” one Harita executive wrote in a 2021 email.

On February 19, 2022, the Guardian published its investigation revealing chromium-6 levels in Kawasi Spring exceeded legal limits, based on tests the newspaper had commissioned.

Harita repudiated the Guardian’s findings, saying it was “actively involved in supporting the Kawasi community by protecting the Kawasi springs with regular water tests” based on Indonesian national standards, and claimed that tests at the spring over the course of nine years had shown chromium-6 levels ranging from just 5 to 40 parts per billion, in line with legal standards.

“The results of the analysis of the spring water during 2013-2021 showed that the water quality of Kawasi springs are suitable for consumption and meets the water quality standards set by the government,” it said in a response to the Guardian.

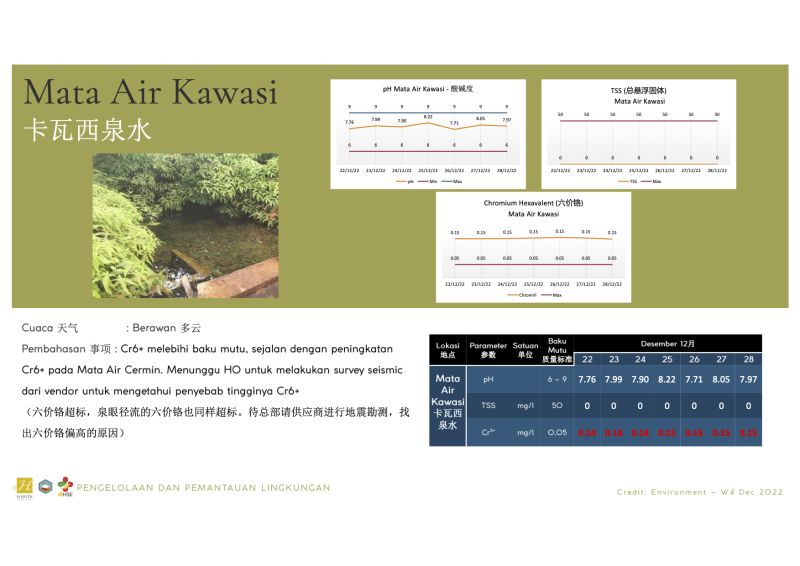

But behind the scenes, the company’s own internal testing told a different story. Internal environmental reports circulated throughout 2022 and into the start of 2023, showed chromium-6 levels repeatedly breached legal and safe limits in the estuary of the nearby Toguraci River and in the spring.

Internal reporting performed in the first four days of the month showed chromium-6 levels in Kawasi’s spring breaching Indonesia’s legal limit on six out of eight readings.

Another reading, taken just two days before the Guardian report went live, showed chromium-6 levels at 128 parts per billion in Kawasi’s spring— more than double the limit.

Harita Group's wastewater discharge point in Kawasi, Indonesia.

Harita Prepares To Go Public

The Guardian report came at a sensitive moment for Harita, just as it was preparing to list shares of PT TBP on Indonesia’s stock exchange. The initial public offering, or IPO, was expected to raise hundreds of millions of dollars. But it also brought renewed scrutiny.

In August 2022, Harita launched an internal investigation into how much chromium-6 was being released by its Obi operation. The probe found that chromium-6 levels at Kawasi Spring had breached Indonesia’s limit of 50 parts per billion on all 30 days that month that testing was conducted.

At the same time, the companies underwriting the IPO were conducting their own reviews.

One leaked due diligence document included answers to questions about the Guardian’s findings. According to the document, which was dated August 30, 2022, Harita said that its monitoring “shows Cr6 [chromium-6] comply with regulation [sic].”

The document was shared with the companies underwriting the IPO, which included branches of BNP Paribas, Citigroup, and Credit Suisse. (The Citigroup subsidiary declined to comment for this story. The other underwriters did not respond to questions.)

But an internal Harita report, circulated just days later, on September 5, said Kawasi’s spring “exhibited persistently high Cr6+ levels." It cited wastewater from its facilities as the source of contamination in the local river. Contaminated groundwater was identified as the source of pollution in the spring.

A page from an internal report showing chromium-6 readings above the legal limit at Kawasi spring in December 2022. The horizontal red line shows the maximum concentration limit of 50 parts per billion. The orange line shows the actual reading of chromium-6 spiking above the legal limit.

In February 2023, just two months before the IPO, the international mining consultancy SRK Consulting completed its own independent assessment of PT TBP’s operations.

In that report, SRK wrote that groundwater operation, surveillance, and monitoring records from the waste facility handling the HPAL plant’s byproducts were “not available.”

In areas where data was provided, “several markers of groundwater quality exceeded the standards” at multiple locations, including for chromium-6, it wrote. The report warned that contaminated water could leach into the ground on Obi island.

That report was shared with the companies underwriting Harita’s listing and became part of the investor prospectus. SRK declined to comment for this story and referred questions to Harita Nickel.

That same month, in February 2023, Harita recorded a chromium-6 reading of 173 parts per billion in Kawasi’s spring, more than three times the legal threshold for drinking water.

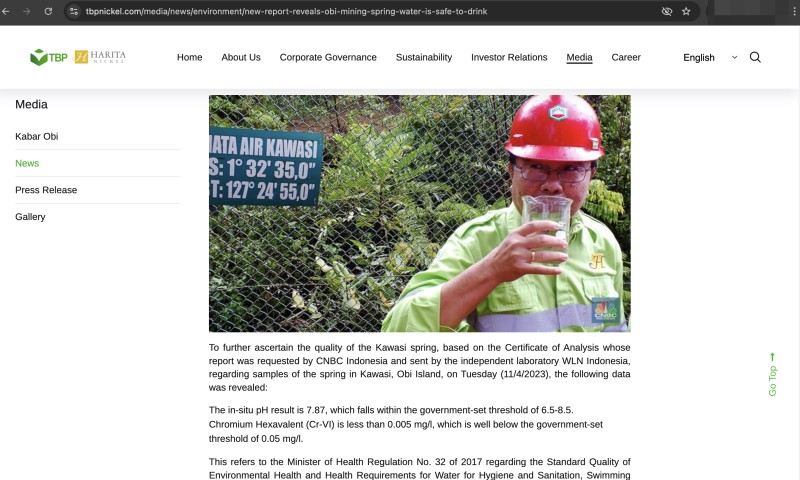

Tonny Gultom raises a glass of water to his mouth in a Harita press release claiming that the water in Kawasi was safe to consume.

The leaked communications end at this point. But the events that followed show that the concerns about chromium-6 contamination did not stymie Harita’s march toward going public. The IPO launched in April 2023, and raised about $660 million, making it one of Indonesia’s biggest listings that year.

A few days before the offering, Harita held a press conference at Kawasi spring, where it was announced that the water was safe to drink. Gultom stood before a group of journalists, and lifted a cup of water to his lips. He held it there long enough for the cameras to capture the moment — but the images did not make it clear if he actually drank.

Jiyoon Kim (KCIJ Newstapa), David Ilieski (OCCRP), and Tom Levitt (The Guardian) contributed reporting. An Indonesian journalist who cannot be named for security reasons also contributed reporting.