A senior member of the Saudi royal family and government adviser arranged citizenship for himself and six family members through Cyprus’ controversial “Golden Visa” program, according to a document obtained by OCCRP.

Prince Saud bin Abdulmohsen bin Abdulaziz Al Saud applied for a passport shortly after his uncle, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman, ousted him as emir of Ha’il province in 2017. Under its economic citizenship program, Cyprus gives out passports in exchange for minimum investments of two million euros.

Since 2013, Cyprus has sold passports to approximately 4,000 foreign nationals, raising more than seven billion euros, according to a recent report by anti-corruption NGO Global Witness.

The European Union has criticized the Golden Visa program for letting people pay their way into the bloc with inadequate vetting and little transparency. The Council of Europe’s anti-money laundering agency, Moneyval, has called Cyprus’s program “inherently vulnerable to abuse.”

Cyprus grants citizenship to almost anyone who has a clean criminal record and big money to invest. Between January 2013 and August 2019, only 56 of 2,700 applicants were rejected, according to official data cited by the news website Kathimerini. A single application can cover multiple people.

Safe Haven — For a Price

Since its launch in 2013, Cyprus’s Golden Visa program has attracted a number of “high-risk” individuals seeking a safe refuge for their families and their wealth.

The Mediterranean island added a condition in 2019 banning public officeholders or people under sanction by other governments, but that came well after Saud’s application.

A December 2017 Interior Ministry document obtained by OCCRP said the ministry was "favorably disposed" toward the prince's application and would present it to the Cypriot Council of Ministers for a decision.

Cyprus does not publish the names of those who hold Golden Visas, but a government spokesman indicated that Saud’s application had been approved.

Cypriot government spokesman Kyriacos Kousios declined to comment in detail, citing confidentiality reasons. However, he said, “all the procedures, criteria and checks have been followed thoroughly prior to the approval of the aforementioned application, with the active involvement of all the competent ministries and authorities, as well as the Interpol and Europol.”

A Rift in the Desert

Saudi Arabia, ruled by the House of Saud since 1932, is known for its fabulous oil wealth and its authoritarian regime. The country is ranked ninth lowest in the world on the Economist Democracy Index for depriving citizens of basic political and civil liberties.

Saud, born in 1948, is a grandson of Saudi Arabia’s founder, King Abdulaziz Al Saud, and a nephew of the current King Salman. He attended Britain’s Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, and has had a long political career as a core member of the royal family.

In 1976, he was appointed deputy governor of Mecca, the most important of the Kingdom’s thirteen provinces, and later became the de facto governor, or emir. From 1999 onward, he was emir of Ha’il province, the Kingdom’s agricultural heartland and one of its most conservative provinces.

He is a member of the Allegiance Council, a group created by King Abdullah in 2007 to let each branch of the Al Saud family vote on matters of succession.

Around that time, Saud opened the door of his palace in Ha’il to a BBC camera crew, which captured the opulence he surrounded himself with. The 2008 BBC program showed him having a family barbecue in the desert; carrying out his daily duties at the governor’s court; attending male-only political discussions; and practicing falconry.

During an interview segment, he was asked about the Kingdom’s strict adherence to sharia law, which many human rights advocates such as Amnesty International and UN member states consider harsh and discriminatory.

“I think public executions are part of our religion, it’s accepted by the majority of the people, it’s not done in secret, it’s done in public and it’s announced on TV and on the radio,” he told the BBC. “We have no apologies. The aspect of chopping hands [of convicted thieves], this is governed by so much, it’s regulated so much to the point where it’s practically impossible to be done. … I’ve been working in the government for 37 years, I haven’t seen one yet.”

“That doesn’t mean, by the way, that we are apologizing about that,’’ he added. “We believe in our Quran, why can’t people get that?”

At the time, Saudi Arabia was trying to project the image of a country striving to modernize while maintaining its traditions and beliefs.

“We change based on the same pace as our people,’’ he said. “You can only change people as much as people want to be changed. ...We do not want to be Westernized.”

Following the death of King Abdullah in 2015, King Salman ascended the throne and appointed his son Mohammed bin Salman — often referred to as MBS — as Minister of Defense.

From this powerful position, MBS started shaking things up, leading Saudi troops into an offensive in Yemen and seeking outside help to overhaul the country’s oil-dependent economy. His efforts have been unpopular within the House of Saud.

In April 2017, Saud was removed as emir of Ha’il and appointed adviser to the royal court, which is usually a retirement position of limited importance, said Steffen Hertog, an associate professor of politics at the London School of Economics who studies the Middle East and Gulf states.

Two months later, MBS was named crown prince.

Discontent escalated in late 2017, when the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Riyadh became an opulent prison for hundreds of business and political elites who were swept up in an anti-corruption probe. Many had to surrender fortunes to win their release.

The crackdown “served the centralization of power in economic matters, bringing princes with business interests and merchant elite in line — and cracking down on some of their corruption,’’ Hertog said.

Saud secured a Cypriot immigration permit — a requirement before applying for citizenship — in July 2017, a month after MBS became crown prince. In December, he applied for a passport for himself and a wife, Princess Hala bint Abdullah A. Al Alsheikh, and five of his 10 children:

Princess Aljowhara bint Saud bin Abdulmohsen bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, born 1978

Princess Nourah bint Saud bin Abdulmohsen bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, born 1973

Prince Abdulmohsen Saud bin Abdulmohsen bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, born 1985

Prince Badr bin Saud bin Abdulmohsen Al Saud, born 1981

Prince Faisal bin Saud bin Abulmohsen Abdulaziz Al Saud, born 1977

To satisfy the visa investment requirement, Saud and his family ordered the construction of two villas, according to the leaked document.

The investment was to be made through two companies, Romolo Ltd and Casipa Ltd, registered in December 2016 with Cypriot lawyer Christos Patsalides as sole shareholder via two proxy companies. Patsalides did not respond to a request for comment.

Another of Saud’s children, Prince Abdulaziz, was appointed director of Romolo and Casipa as well as one of Patsalides’ proxy companies, Sagita Ltd, in January 2018. Abdulaziz was not listed in the 2017 Golden Visa application.

The timing of Saud’s move to gain foreign citizenship suggests he may have been unnerved by the new crown prince, Hertog said.

“Many are afraid of MBS within the royal family due to his draconian nature,” Hertog said.

Changes in the Kingdom may prove difficult for some royals, said Cinzia Bianco, a researcher and analyst at the European Council of Foreign Relations who specializes in the Arabian peninsula.

“The crown prince’s ascent has long polarized the large Saudi royal family,’’ Bianco said. “Its ‘old guard’ includes senior members of the family who are highly skeptical of the current trajectory, disruptive as it is of decades-old traditions in all fields.,”

That disruption, coupled with plunging oil prices, has prompted Saudi businessmen to move wealth out of the country and seek second passports. Cyprus and Malta have been the most popular destinations.

In Saudi Arabia, dual citizenship must be personally authorized by the king. Failing to get his approval can result in the loss of native citizenship, seizure of assets, and expulsion from the Kingdom.

“That a senior member of the royal family may have had the king’s permission to purchase a foreign passport sounds unlikely,” Hertog said.

The Saudi government did not respond to an OCCRP request seeking comment.

Though several high-profile citizens have sought and obtained citizenship, Saud and his family are the only Saudi royals who have been publicly identified.

In 2015, Abdulrahman bin Mahfouz, a son of deceased Saudi banker Khalid bin Mahfouz, was given a Cypriot passport, along with 36 family members. In 2017, two Saudi families reportedly acquired 62 passports in Malta. That year Saudi nationals reportedly accounted for 17 percent of new Maltese citizens.

Patsalides, the lawyer who incorporated the companies used by Saud to buy the Cypriot villas, also represents bin Mahfouz. OCCRP has identified 17 companies registered in Cyprus in which both Patsalides and bin Mahfouz serve as directors.

An Island and a Kingdom

Cyprus’ Ministry of Interior submitted Saud’s application to the Council of Ministers for approval and also notified the parliament just days before Cypriot President Nicos Anastasiades made an official visit to Saudi Arabia in January 2018 — the first by a sitting president of Cyprus.

The meeting included the signing of many bilateral agreements, such as a memorandum of understanding regarding political consultations between Ministries of Foreign Affairs.

Unlike other countries, Cyprus does not seem to shy away from maintaining a friendly relationship with Saudi Arabia.

The Kingdom was widely condemned when it stepped up arbitrary prosecution of peaceful dissidents and activists in 2018, and faced international criticism after Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was murdered in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. Crown Prince Mohammed is accused of having ordered the killing, which he denies.

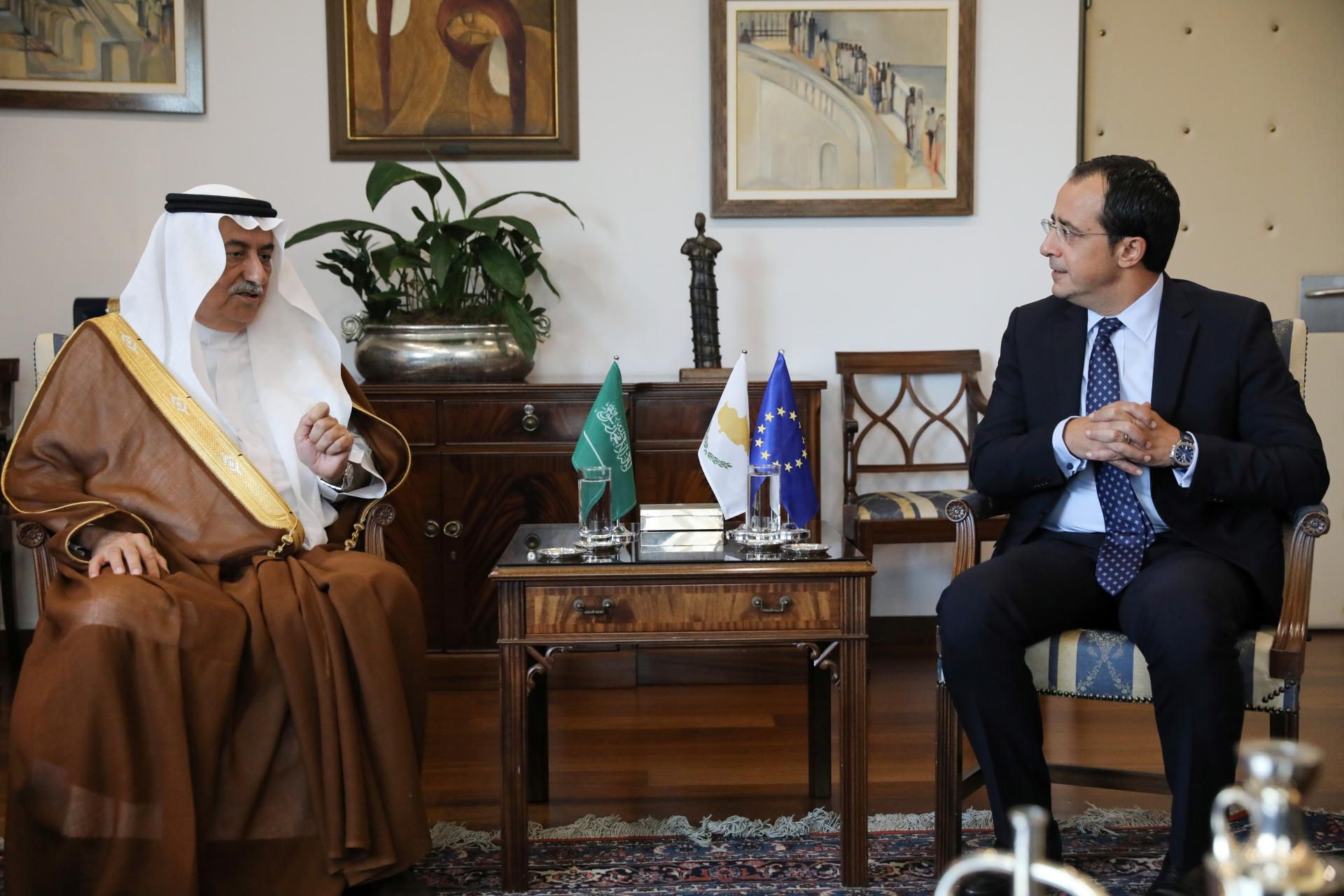

In September 2019, then Foreign Minister Ibrahim bin Abdulaziz Al-Assaf became the first Saudi official to visit Cyprus. In January 2020, Cypriot Foreign Minister Nikos Christodoulides was received by King Salman in Riyadh.

“The past months have seen an unprecedented level of diplomatic engagement between Saudi Arabia and Cyprus,’’ Bianco said. “To meaningfully explain the interest in the region, one has to look beyond the borders of both, towards Turkey, and factor in energy, security, foreign policy, and trade.”

Cyprus’ location as a gateway to Europe and its history with Turkey create a complex geopolitical situation that seems to play a part in its diplomacy with Saudi Arabia, Bianco said.

“While Saudi Arabia supports Cypriot sovereignty against the impingement of Turkey, which is the only country that recognizes the breakaway Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Cyprus could provide the Saudis an opportunity to improve their relations with the European Union as a whole,” she said.

Correction: This story was updated to reflect that Saud's former title was deputy governor of Mecca. An earlier version of the story listed it as deputy director.