The documents outline specific ways to mislead regulators and avoid red flags to regulators and law enforcement. At least one of the banks denies creating the documents.

Riga, the Latvian capital, has long been home to a thriving offshore banking sector that has helped criminals and corrupt officials to siphon stolen money from the former Soviet countries.

Latvian banks have laundered money for the perpetrators of a number of high-profile scandals including the Sergei Magnitsky case, which may be the largest tax fraud case in Russian history; the Russian Laundromat, a criminal scheme that laundered at least US$ 20 billion; or, more recently, the case of Sergey Roldugin, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s friend, whose controversial transactions were detailed in the Panama Papers.

The internal documents, if true, show that the banks are not disinterested parties who are used by criminals but are directly involved in the process. The documents include specific guidelines and rules for those who wish to use their services and to take advantage of their unique expertise.

The leaked documents include emails between Latvian-based Ukrainian banks and government officials as well as banking transfers, contracts and other communications. The documents often appear in the names of specific offshore corporations, explaining how to use their services. While the relationships between the offshores and the banks are not clear, some of the documents indicate they were created by bank employees.

Some of the banks have denied creating the documents and blame staff for collecting the documents from other sources, including the Internet and consultants. Others have not returned comment.

Money-Laundering Manuals

The documents indicate that at least three Riga banks appear to administer or promote offshore shell companies which are used for money laundering-like activities. These shell companies are based in secretive tax havens such as Panama, Belize or the Seychelles, and their bank accounts are used to “pool” potentially dirty money from customers before moving it around through other secret bank accounts, called “layering” in money laundering parlance.

In order to launder money, a money launderer sends money around the world to many different bank accounts in many different companies through a series of transactions that appear legitimate but are not. Money laundering laws often require banks to provide contracts and other proof that each transaction is legitimate. Once the money has moved through various fake companies, it is usually transferred back to the offshore company of the original owner of the dirty money.

The “pooling”and “layering” processes are critical to the success of any money laundering scheme, because they make the ownership and ultimate destination of the cash far more difficult to trace. One problem Latvian-based banks face is that to wire money abroad, they must set up correspondent accounts with much larger banks in Western Europe and the United States.

Correspondent accounts allow banks to transfer money to other countries where they don’t have branches. However, these correspondent banks often have more stringent standards than Latvia and are more likely to be on the lookout for money laundering or other crimes.

The documents include a lot of advice on how to fool correspondent banks.

Teaching the Crime

The documents detail ways to set up business transactions that look convincing to banking regulators. The techniques are designed to keep transactions off the radar of anti-money laundering monitors in Western banks. Many of the instructions are designed to help clients work with and protect the bank’s own fake companies.

For example, the documents contain helpful instructions, such as how to fabricate convincing invoices. One of the companies in the documents offers the service of being a partner for fake trades – a technique used in money laundering to hide the source of money.

And some of the advice seems rather obvious: in one of the documents, the company warns clients to be careful to make fake invoices only for products that their fake company is supposed to be trading.

One company that offers such instructions is Belize-based Bormilla Solutions, which has a bank account at Latvia's AS Privatbank. The company specializes in fake operations in the areas of construction materials, industrial equipment, and instrumentation. Other fake companies work in other industries ranging from delivering sanitary equipment to electronic goods.

Bormilla, like the others, is actually an empty shell with no real offices and no tangible business according to the documents.

According to the Word document’s metadata, it was created by an employee of Privatbank Latvia. The employee, who has since moved to another bank, did not respond to attempts to contact her.

Kayten Trading, a Panama shell company that also has an account at Privatbank, provided clients with a similar service and similar advice. Privatbank, a subsidiary of Ukraine's eponymous largest bank, failed to answer queries about the documents.

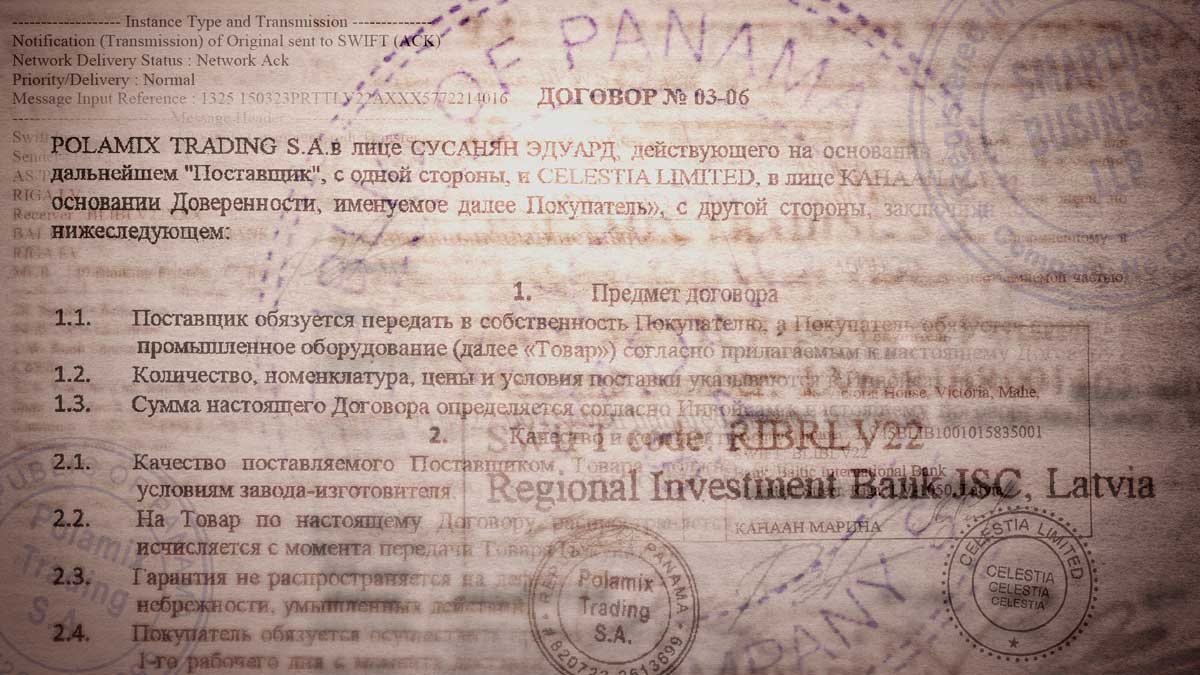

Another Latvian bank with similar services is the Regional Investment Bank, a former subsidiary of Odessa-based Pivdennyi Bank now owned by shareholders of Pivdennyi. The OCCRP reporters found documents that described similar services for three shell firms: two registered in the United Kingdom, Smartus Business and Gerevit; and the Panamanian firm Polamix.

The documents warn that funds paid into the account will only be 'released' when the client provides suitably convincing contracts, with color stamp and signature, to back up the incoming wire transactions.

Reporters for OCCRP asked Latvia’s Financial and Capital Market Commission (FCMC), which supervises banks, to comment on the propriety of banks supplying such how-to documents to customers.

The “FCMC has requested the banks to submit information about the companies indicated in the documents provided,” the FCMC said.

The Regional Investment Bank said it “did not draft or prepare the documents” OCCRP sent for comment and could not provide any further comment due to client confidentiality.

A plausible contract

A document apparently produced at the Baltic International Bank (BIB) (a bank involved in numerous fraudulent transfers) indicates that bank employees seemingly provided instructions on how to draw up plausible contracts.

In March, Latvian financial authorities imposed a € 1.1 million fine on BIB for repeated violations of money-laundering rules.

The instructions, entitled “Requirement for contracts” and “Rules for documents,” tell clients how to correctly utilize what the BIB refers to as “our companies,” and in particular how to correctly compile supporting paperwork for transactions.

The set of instructions urge clients to make payments exclusively with reference to the goods listed as being for sale by the fake company. “We draw your attention once again — follow the rules for specifying the purpose of payment reference in the strictest possible way,” the manual states.

“Payment can only be made for the purchase/sale of the goods specified in the details of our company. We have never listed any services whatsoever and never will, only goods,” the BIB employee urged clients.

The instructions also remind clients that contracts should include mention of the company representatives as listed, specifying their positions. “Representatives of our companies always act on the basis of a power of attorney,” the BIB document said.

The BIB documents also instruct clients how to write plausible fictitious contracts to support wire payments “in the light of stricter requirements from the regulatory organs.”

“The delivery conditions specified in the contract or invoice should be realistic: When you specify goods, you have to think how they are going to be 'shipped' (weight of the cargo, volumes, address of the manufacturing plant, type of transport: road, rail or ship.) In the case of 'shipping' of goods with very large volume or size, please specify a factory close to railroad or port,” the bank employee advised clients.

For example, the manual advises that if a client’s fake invoice includes the sale of heavy equipment, the client should create a record of correspondence between a crane company needed to move the goods.

“As a rule, shipping or freight is done by the manufacturer's plant at the cost or at the order of the seller or purchaser. If there is no port or rail connection near the manufacturer's plant, than the question arises of how the goods are moved to port or railway,” the document reads.

“If you don't provide transport documents, you may have picked up the goods in your own vehicle, but this is not realistic unless you own a fleet of ships, or one or two hundred Kamaz trucks, and it means you should have to hire a carrier, who would provide transport services together with the relevant documents,” the document continues.

According to the BiB document, the total contract sum must be below € 700,000 with no single payment greater than € 300,000 because this leads to money laundering monitors asking for transportation documents.

The Word document metadata indicate BIB as the company where the author worked, and the document was last saved by Dargevica S., which may correspond to Santa Dargevica, a BIB employee, according to her social network profile.

When OCCRP asked BIB about the user’s manual, BIB spokesperson Antra Laumane said: “The information received has been transferred to respective internal departments and further measures shall be taken as necessary.”In later discussions, BIB said that it had no part in the writing of the guidelines.

The bank said that the documents might have ended up in the computers of the employees because they receive large quantities of documents from their clients as well as third-party information and suggestions by consultants. It added that these guidelines might have been created by a consulting firm and ended up in the hands of bank employees through the use of mailing lists.

Clarification: The story was changed to more precisely explain sources used.