Reported by

When Texas-based healthcare giant Steward Health Care failed spectacularly in 2024 amid allegations of fraud, bribery, and corporate spying, OCCRP revealed that its landlord, Medical Properties Trust (MPT), had played a central role in the hospital provider’s demise.

MPT seemingly threw Steward a lifeline by acquiring its buildings for vastly inflated sums, but in the end, the hospital provider was left with soaring debt and rent obligations that placed it on the hook for more than a billion dollars.

Those rent payments contributed to MPT’s bottom line and the publicly-listed real-estate investment trust (REIT) benefited by its stock price reaching higher and higher levels. At the same time, its tenant moved toward bankruptcy.

Steward's Nashoba Valley Medical Center in Ayer, Massachusetts, which closed on August 31, 2024.

Now, OCCRP has discovered that MPT executives, who were concerned their cash cow may be failing, arranged a similar scheme with another U.S. hospital company, Prospect Medical Holdings.

Leaked emails and other documents obtained by OCCRP show that MPT knew Prospect, which once owned 16 facilities in southern California, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Connecticut, was already heavily in debt and nearly bankrupt.

Still, MPT rolled out the same playbook it had used with Steward: It overpaid Prospect for its real estate, then charged it exorbitant rent to compensate. The income MPT reported helped it appear to be highly profitable, maintain a high stock price, and reap big dividends for its owners — an estimated $3.2 billion from 2016 to 2022. Meanwhile, Prospect lurched closer to bankruptcy under the heavy rent obligations, while MPT took on bad debt that would eventually lead to major losses and a plummeting share price.

The type of real estate deal that Steward and Prospect made with MPT, called a sale-leaseback, can be attractive for commercial companies that need working capital to modernize their facilities or invest in the latest technologies to improve profits.

But hospitals are different, experts say. They do not generate large profits and have to be more careful.

"Most for-profit and non-profit hospitals refuse to sell their property because that is an important asset, especially if they need to qualify for loans to improve facilities or invest in new technologies," said Rosemary Batt, a professor emerita at Cornell University and expert in healthcare financialization and private equity.

Prospect Medical Holdings' website.

In both cases, the documents show, Steward and Prospect largely used the money from MPT’s property purchases for purposes other than improving healthcare: to buy back ownership from private equity firms that had previously saddled the hospital chains with huge debt, and to make the new rent and debt payments to MPT.

In fact, though the huge sums MPT paid for the hospital properties were not technically loans, in practice internal documents showed it planned the deal to serve much the same purpose, providing operational cash to Prospect. This raises questions about whether the transaction violated U.S. law governing REITs, which doesn’t allow loans that finance a tenant’s operations.

Ultimately, neither company could afford to pay such high rents for long, so MPT found creative ways to get more money into their hands, prolonging the appearance that its tenants were financially sound. Often, this came in the form of additional mortgages on properties already mortgaged well beyond their worth. To raise the money, MPT issued new shares of stock and notes and sold them to institutional investment firms that manage investments like savings plans and pension funds.

In response to the collapse of Steward Health Care, which was extensively reported on by OCCRP in partnership with the Boston Globe, Massachusetts senators Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey described the mechanism through which MPT provided capital as resembling a “Ponzi scheme,” and accused MPT and Steward of having “plundered” their hospital operations.

In the case of Steward, the private equity giant Cerberus Capital Management, and Steward’s former CEO extracted more than $1.3 billion from the ailing provider even as patients suffered from deteriorating care.

MPT, according to leaked records, did not make public the full extent of its financial support to the hospital operators. In fact it assured shareholders in calls that the companies were financially healthy. In 2020, for instance, MPT publicly stated that Prospect was contributing significantly to its bottom line even though it knew the condition of Prospect’s finances.

The exterior of Roger Williams Medical Center in Providence, Rhode Island, on November 29, 2022. The hospital, owned by Prospect Medical Holdings, is currently under bankruptcy proceedings.

Prospect filed for bankruptcy in January 2025, leaving institutional investors, pension funds, and others with large losses. Its Chapter 11 filing, a process through which debt-hit companies seek court protection as they reorganize their finances, showed that the hospital firm had at least $2.3 billion in debt. MPT continues to operate, although it has not been profitable in recent years.

When reached for comment, MPT told OCCRP that it “categorically rejects the false and misleading premise of this story. … Allegations that MPT’s business model contributes to the financial distress of hospital operators is as false as it is at odds with how the healthcare system actually operates. Rent under MPT’s leases is virtually never the primary cause of financial stress for hospitals.”

Prospect, now in bankruptcy, did not respond to questions. Thomas Califano, a lawyer at Sidley Austin LLP, the firm representing Prospect’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy, told OCCRP he could not comment on an ongoing case.

Private Equity Buyout

Founded in California in 1996, Prospect expanded into full hospital operations in 2007 with the acquisition of Alta Hospitals System LLC, a community-based hospital chain in California. In late 2010, the private equity firm Leonard Green & Partners acquired a majority stake in Prospect through a $363-million leveraged buyout — a purchase made primarily with borrowed funds. As part of that transaction, Prospect’s chairman and CEO, Samuel Lee, and its president, David Topper became significant minority shareholders.

Batt, the expert in private equity, told OCCRP that a business model built on quick returns is not suited to healthcare companies.

“Private equity firms view healthcare organizations as ‘financial assets’ to be bought and sold — completely divorced from the human care mission of healthcare organizations,” she said.

Private equity firms view healthcare organizations as ‘financial assets’ to be bought and sold — completely divorced from the human care mission of healthcare organizations.

Rosemary Batt, Professor Emerita, Cornell University

By 2018, Prospect had a $1.1 billion debt, a portion of which came from funds used to pay a $457-million dividend to Leonard Green & Partners, Lee, Topper and other minority shareholders, through a leveraged dividend recapitalization, according to a 2021 Rhode Island attorney general's decision approving the sale that reviewed Prospect’s financial condition, ownership structure and transactions during Leonard Green’s control. Also known as a recap dividend, this controversial practice allows owners, typically private equity firms, to saddle a company with significant debt so they can pay themselves and other shareholders large dividends.

According to the attorney general's findings, by the time the dividend was paid out, Prospect had only one day’s worth of cash on hand, while its total liabilities had ballooned to over $2.4 billion.

The following year, with Prospect in financial peril, its credit rating downgraded, and with very little in earnings and assets left, Leonard Green & Partners looked for an exit strategy, seeking new investors, but ultimately pursuing the sale-leaseback deal with MPT. The arrangement was finalized in August 2019. MPT agreed to pay $1.55 billion for 16 properties that Prospect’s own analyses valued at $533 million. (To finance the acquisition, MPT raised capital by issuing $900 million in unsecured notes — promises to repay borrowed money — and $858 million in common stock in July 2019.)

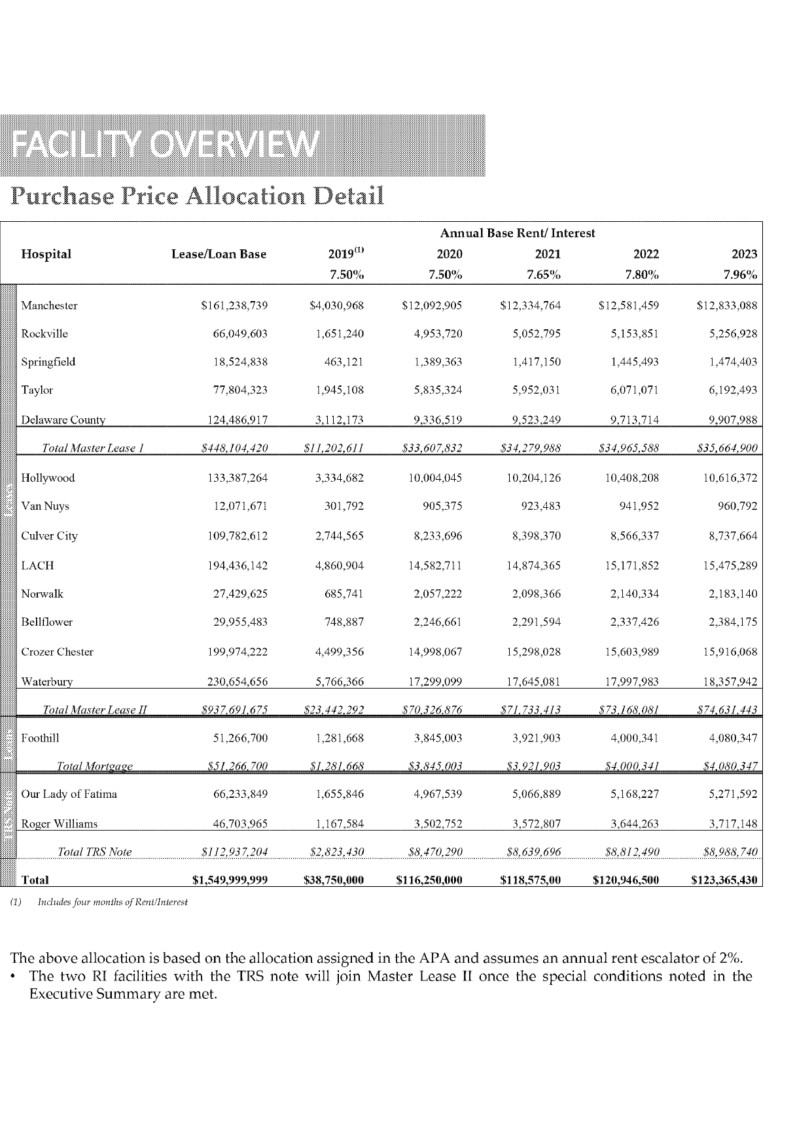

Thirteen of those properties were leased back to Prospect under two 15-year master leases. The rent was tied directly to the $1.55-billion purchase price rather than prevailing market rates. The leases also included a plan for the rent to increase over time, with a 7.5 percent annual interest rate that would escalate over the life of the leases.

With interest, MPT calculated the first year of annual rent at $116 million. By 2023, it would increase to $123 million with interest.

An excerpt from Prospect Medical Holdings’ 2019 report.

That same year, U.S. Senator Charles Grassley, a Republican from Iowa, launched a broader inquiry into sale-leaseback arrangements in the healthcare sector after allegations of sexual assault surfaced at an Iowa health care facility owned by another private equity firm and subject to a sale leaseback agreement with MPT. Grassley was interested in how such deals can influence hospital finances and operations.

According to a report from that inquiry, Prospect paid a total of $645 million in dividends to Leonard Green & Partners and other shareholders between 2011 and 2019, plus more than $13 million in fees — leaving the hospital provider in financial distress. As well as recap dividends, some of these returns were made possible by “significant asset sales [and the] issuance of securities” that did not require the approval of the Prospect board, according to Grassley’s report.

Towards the end of 2018, Prospect “faced mounting financial and operational challenges,” the Grassley report states, “including internal investigations into financial practices, escalating long-term debt, and delays in critical audits that left the company in default with lenders.”

As it had with Steward three years earlier, MPT snapped up Prospect’s hospitals “but saddled [Prospect] with over $100 million in annual rent, exacerbating its financial strain,” the Grassley report adds.

Senator Chuck Grassley speaking during the 2015 Lincoln Dinner hosted by the Iowa Republican Party at the Iowa Events Center in Des Moines, Iowa.

The deal did little to right Prospect’s sinking ship. The Grassley report states that even after the sale-leaseback went through, “at the end of fiscal year 2019, [Prospect] had total liabilities of $2.8 billion and a net income of negative $298 million.”

Leonard Green & Partners did not respond to questions sent by email. A receptionist confirmed the firm had received the questions and was not going to respond.

‘Project Prince’

Among the most illuminating documents reviewed by reporters was an internal underwriting evaluation of Prospect’s finances by MPT.

The report was part of "Project Prince," a plan to acquire Prospect’s real estate to diversify MPT’s holdings. It broke down the $1.55-billion price tag and the considerations that informed it, showing that MPT viewed the deal more as a recapitalization of Prospect than a real estate purchase — a strategy similar to MPT’s handling of Stewart, which was now approaching bankruptcy.

According to the report, the $1.55-billion purchase price included funds from MPT that were not related to the real estate itself, including “working capital,” payments related to an asset-based loan, the payoff of Prospect’s existing debt, and payouts to managers.

The majority of the money — about 83 percent of the $1.55 billion paid for the hospital provider’s real estate — would go towards covering existing Prospect debt, the report shows. For example, MPT designated $1.11 billion to pay off a single Prospect loan, a significant portion of which came from funds used to pay a $457-million dividend taken by Leonard Green & Partners and other shareholders.

Excerpt from Prospect Medical Holdings’ 2019 report, showing how MPT justified the $1.55‑billion purchase.

In effect, MPT’s purchase of Prospect’s real estate allowed the firm to pay off a significant amount of the firm’s debt. While these huge sums were not technically loans, in practice they served much the same purpose, providing operational cash to a financially distressed tenant. This practice raises questions about whether the transactions violated U.S. law governing REITs.

To maintain their tax-exempt status, REITs must earn at least 95 percent of their gross income from real-estate-related sources, such as rent from properties or interest from mortgages tied to the value of a property. Loans that are not tied to real estate or are used to finance tenant’s operations are not allowed.

While MPT claimed the new, outsized rents were exclusively from the real estate, the Project Prince report shows it included debt repayments.

By wrapping a significant portion of Prospect’s existing debt into the sale price and collecting it back as inflated rent payments, MPT may have been collecting income from a de facto loan rather than a legitimate real estate transaction.

The report also shows that MPT was interested in Prospect as a way to dilute its exposure to Steward, which a separate leak of internal documents showed was veering towards insolvency. According to Project Prince, the Prospect acquisition was desirable because it would bring the Steward share of MPT’s portfolio from 34.5 percent to 27.2 percent.

An excerpt from Prospect Medical Holdings’ 2019 report.

To sell the deal to its board, MPT presented a high valuation of Prospect that included highly subjective factors like “goodwill,” valued at $302 million, and “intangibles” listed for another $26 million, indicating that at least $325 million of the ascribed value was not tied to physical assets.

“The issue here was that MPT was effectively financing another exit by a [private equity] firm ... and knowingly increasing Prospect's leverage to a suicidal level with unaffordable rents, thereby dooming Prospect. It wasn't a case of legality at the outset, rather perverse intentions,” said Rob Simone, a REIT analyst formerly with Hedgeye.

As in the Steward deal, MPT appeared to be helping Prospect get rid of its private equity managers as part of the deal. At the same time the sale-leaseback deal was finalized, Leonard Green & Partners agreed to sell its 60 percent stake back to Prospect itself for a cut-rate price of $12 million, highlighting how little the healthcare company’s shares were really worth.

Project Prince also shows that Leonard Green & Partners and other shareholders stood to benefit from a further $50.3 million recap dividend bonus from MPT as part of the sale — something that was not disclosed in MPT’s public filings.

The issue here was that MPT was effectively financing another exit by a [private equity] firm ... and knowingly increasing Prospect's leverage to a suicidal level with unaffordable rents.

Rob Simone, REIT analyst

In an email to MPT CEO Edward Aldag, a senior executive at the trust said he talked with Prospect and believed they wanted Leonard Green to “take his money and go away” and for MPT not to impose any restrictions on the company, so that it could “cleanup its balance sheet” which the executive confirmed.

Aldag and other senior executives did not respond to questions from OCCRP.

Like the Steward deal, the Prospect sale put MPT in the driver’s seat, making Prospect heavily reliant on its new landlord — and largest debt holder.

“Had MPT paid a price that made more sense for a distressed and insolvent Prospect, almost by definition all the values ascribed would have been lower,” said Simone, who publicly shared analysis of the deal at the time. “Our view was that MPT management wanted three things primarily: to dilute their exposure to a failing Steward, to appear to be paid higher rents, and to prop up their stock with artificial earnings growth.”

And with the deal they did exactly that, documents show. But as with Steward, problems were coming fast. Prospect, too, was about to enter a death spiral

A Quiet $100-Million Loan

When MPT became its landlord, Prospect was already in poor shape from years under Leonard Green’s management. In addition to its debt, almost all of Prospect’s hospitals were ranked among the worst in the U.S. for quality of care, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the government agency that provides healthcare coverage to more than 160 million Americans on Medicaid and Medicare. “All but one of [Prospect’s] hospitals were ranked in the bottom 17 percent of CMS’ quality of care rankings” in 2020, the Grassley report states.

Meanwhile, MPT was reaping significant rewards from its deals. Steward and Prospect accounted for two of its top three income sources. Between 2016 and 2022, its stock price more than doubled, reaching an all-time high of over $24 per share in January 2022. Over the same period, the company’s management issued an estimated $3.2 billion in dividends to itself and its shareholders.

But MPT’s practice of lending large amounts of debt to risky companies was beginning to catch up with it. By then, 72 percent of its holdings were general acute care hospitals like those run by Steward and Prospect. Those hospitals increasingly resembled high-risk, inflated financial assets propped up by MPT's cash, rather than robust sources of rent. MPT’s own disclosures to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) show that even in the year of its peak share price, the company was losing a lot of money.

By 2022, Prospect was insolvent. Despite the inflow of cash following MPT’s deal, annual reports starting from 2019 show the firm had hundreds of millions in unpaid bills to vendors, staff, and for taxes, and negative equity capital. Its total liabilities exceeded its assets by more than 75 percent. By the middle of 2022, Prospect began deferring rent payments, and bankruptcy appeared a real possibility.

But instead of Prospect facing bankruptcy, MPT moved to prop up its tenant with a $100-million loan.

An official property deed document filed in Orange County, California, shows MPT loaned $100 million to Prospect in two advances in May 2022. Just a few months later, on an August 2022 earnings call, CFO Steven Hamner publicly denied any plans to lend money to Prospect. He failed to mention that the company had already provided a significant loan. The so-called “mortgage” loan was disclosed just days later in a quarterly financial disclosure form filed with the SEC. The Orange County deed, which was signed by Hamner, showed he had personally confirmed it.

The $100 million was loaned as a mortgage to Foothill Regional Medical Center, one of Prospect’s facilities in Southern California. According to internal documents, that brought the total amount of mortgage loans on that single piece of real estate to $151 million. This huge figure dwarfed the $15 million Prospect had paid for the facility, and its operations, in 2014.

The discrepancy is even more apparent today. Prospect’s bankruptcy data shows Foothill’s real estate and operations were recently sold to the U.S.-based health provider Astrana Health for just $18.6 million, a transaction that highlights the extent to which MPT artificially inflated its property values.

The Pennsylvania Hospitals

MPT’s internal communications showed the company’s executives were fully aware they were overpaying for real estate.

As part of the 2019 sale-leaseback deal, MPT bought four Prospect medical properties in Pennsylvania for $420 million — a price that struck experts as seriously off. The same four properties had been purchased for just $153 million three years earlier.

The leaked documents show a Wall Street Journal reporter questioned MPT about why it valued the hospitals at triple the price Prospect had paid for them in 2016. The question led to a behind-the-scenes discussion among MPT managers.

In an email to Hammer and Aldag, a senior adviser to Aldag wrote: “The transaction was a sale-leaseback financing transaction and the real estate is collateral. The dollar figure is not an indication of the value of that real property collateral.”

The statement essentially acknowledged that MPTs valuation was not based on market values. In another email, the adviser advocated against discussing real estate valuations publicly, saying MPT “certainly cannot say that the dollar figure is not an indication of RE [real estate] value.”

End Game

Burdened by unsustainable rents, the Pennsylvania hospitals soon ran into trouble. By 2022, MPT lowered their book value from $420 million to $250 million and wrote off $112 million in overdue rent. Meanwhile, questions from the media and analysts about the Pennsylvania hospital valuations and growing scrutiny of Steward were raising serious concerns about the quality of MPT’s earnings.

MPT believed it needed a new asset to replace the fast-dropping value of the four hospitals. It hired Barclays to assess whether one of Prospect’s affiliated value-care businesses, Prospect Health Plan (PHP), could fill that role. Prospect, now deeply in debt, agreed to a deal to give PHP to MPT to offset some of its debt.

According to a leaked copy of Barclays’ report from April 2023, PHP could be used to “recoup” $420 million from the Pennsylvania hospitals over time if the business was well run.

Health care workers joined legislators at Connecticut's state capitol building on November 13 to call for Prospect Medical Holdings to leave Connecticut, citing underinvestment in three hospitals Yale New Haven Health is trying to acquire.

Barclay noted that PHP had less than $2 million in net income. It also warned that it was a “‘value-based care”’ company, meaning healthcare providers were paid not on what services they provided but rather on the patients’ health outcomes. This meant the margins were much smaller than classic healthcare plans and PHP outsourced its insurance underwriting giving them even less control over costs. PHP lagged behind other similar operators, the Barclays report noted, in part due to the fact that two-thirds of its membership was drawn from Medicaid users, which meant lower paid premiums and tighter margins. It wasn’t going to return blowout profits, but if managed carefully over years it could have reliable returns.

Barclays valued PHP at between $600 and $800 million.

MPT went ahead with a deal in May 2023, taking a 49 percent equity stake in PHP Holdings, the parent company of PHP, in exchange for retiring $646 million of Prospect’s debt. MPT valued its shares on its books at $699 million, which was significantly more than the Barclays valuation, despite the company's less than stellar financial underpinnings. The deal would later include other PHP Holdings assets such as Foothill Medical Regional Center, the California-based hospital worth $18.5 million.

As part of the deal, MPT returned some assets, including the four Pennsylvania properties to Prospect. The agreement stipulated that if Prospect sold them, then it must pay MPT $150 million.

Like many of MPT’s investments in financially troubled companies, the PHP deal also turned sour.

In its 2024 annual report, MPT admitted it could no longer stem its losses and could not sell any of the remaining East Coast hospitals, nor could Prospect sell the Pennsylvania hospitals.

With bankruptcies now looming at both Steward and Prospect, Prospect and MPT agreed to sell PHP Holdings in November 2024 to another healthcare company. Astrana, a California-based healthcare firm, offered $745 million for PHP Holdings but the deal took until July 2025, when the final price was set at $708 million. MPT has so far only earned $2.3 million from its 49 percent shares in PHP Holdings, or just 0.3 percent of the original valuation of the company.

In January 2025, Prospect’s Chapter 11 filing in the Northern District of Texas, listed debts of at least $2.3 billion to over 100,000 creditors and sought $1.1 billion in protection. The filing came as Prospect faced probes or calls for probes by authorities in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Pennsylvania over suspected government fraud and other issues. The four Pennsylvania hospitals were closed by May 2025, with Prospect citing an inability to find a buyer.

Propelled by its deals with Prospect and Steward, MPT’s share price peaked in early 2022 at $24 a share. Today it rests at less than $5, and MPT has reported consistent losses. It is expected that some or all of Steward and Prospect’s multi-billion-dollar debt to MPT will be written off in bankruptcy.

“Prospect and Steward were propped up by MPT,” said Batt, the expert in private equity. “There was a mutual dependence. … If one went down the other would likely go down too – which has been happening in these cases.”

MPT, in a statement to OCCRP, said: “As an investor in hospital real estate, MPT’s strong interest is that each of the hospitals in which it invests remains open and serving its community.”