A former head of Libya’s state contracting office who served under the country’s former dictator Muammar Gaddafi is being investigated because he is believed to have stolen 20 percent of the value of the contracts his office handled.

Now, a new document leak reveals that the former official may have used at least 16 bank accounts and seven companies in Cyprus in the alleged crimes. The newly revealed mechanisms form just part of his hidden global empire of more than 100 companies, luxury real estate holdings, and other assets.

From 1989 until 2011, Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba, once mayor of the coastal city of Misrata, controlled the Organization for Development of Administrative Centers (ODAC), a major public agency tasked with developing the country’s infrastructure. During his tenure as its director, Dabaiba awarded 3,091 contracts with a total value of 45.4 billion Libyan dinars (US$ 33 billion). In an interview to the Oxford Business Group, Dabaiba said that ODAC’s budget in 2008 was $6.8 billion.

The Tripoli-based Libyan authorities believe that Dabaiba may have misappropriated between $6 and $7 billion of that amount using such techniques as charging excessive “commissions” and awarding tenders to companies that were linked to him or that he secretly owned outright. In 2013, they launched a criminal investigation into his activities, as well as those of his brother Yusef Ibrahim Dabaiba and his sons Ibrahim Ali Dabaiba and Osama Dabaiba. They have also enlisted international investigators to try to recover the illegally obtained assets, even offering a percentage of the funds as a finder’s reward.

In the run-up to the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, Dabaiba knew a loser when he saw one, and switched his allegiance to the rebels. As Libya descended into a brutal civil war that claimed the lives of thousands of his countrymen, his offshore empire was ready to serve him well for a life in exile. (Dabaiba is now believed to be living in Istanbul.)

Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba, formerly mayor of Misrata and head of major Libyan state procurement agency ODAC under the Gaddafi regime. Credit: Al-Mostakbal The new trove of financial documents leaked to reporters, as well as interviews with Libyan officials investigating Dabaiba and files from that investigation, reveal more about how his schemes worked.

Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba, formerly mayor of Misrata and head of major Libyan state procurement agency ODAC under the Gaddafi regime. Credit: Al-Mostakbal The new trove of financial documents leaked to reporters, as well as interviews with Libyan officials investigating Dabaiba and files from that investigation, reveal more about how his schemes worked.

Just some of the Libyan official’s dealings involved Cyprus. But Dabaiba’s use of the country’s financial services is particularly sensitive given its recent efforts to clean up its image as a haven for money launderers and other criminals.

Reporters for the Investigative Reporting Project Italy (IRPI) and an independent reporter working for OCCRP in Cyprus have spent the last six months tracing where some of that missing money may have ended up — and to what purpose.

Public Procurement, Personal Profit

Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba’s rise was as rapid as it was lucrative. Most likely born in 1945, the former geography teacher became mayor of the key coastal city of Misrata not long after Gaddafi seized power in 1969. In 1983, Dabaiba started working at ODAC, going on to serve as its director from 1989 to 2011.

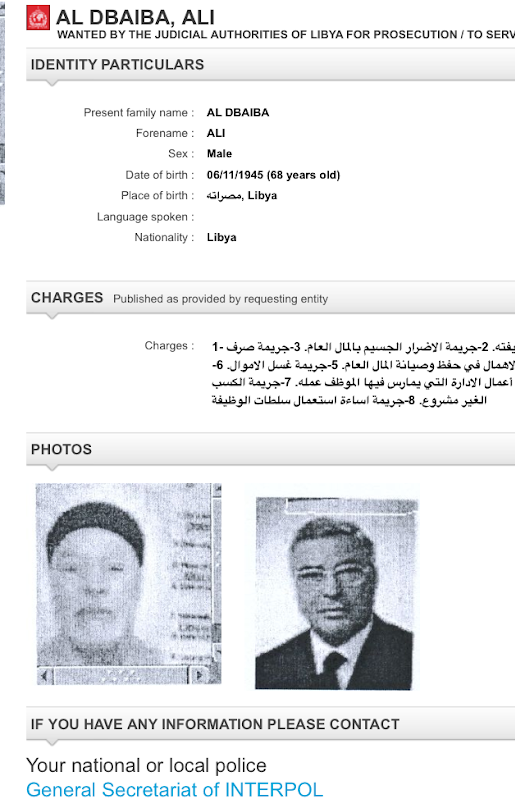

Interpol Red Notice issued for Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba (since retracted). Credit: WayBack Machine Internet Archive ODAC’s purpose was to use some of Libya’s considerable oil wealth to develop the country’s public infrastructure. As its head, Dabaiba played a decisive role, negotiating contracts and overseeing payments to suppliers. But he also had other loyalties; documents show that while on ODAC’s payroll, he ran several companies abroad that benefited from his leading role at the agency.

Interpol Red Notice issued for Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba (since retracted). Credit: WayBack Machine Internet Archive ODAC’s purpose was to use some of Libya’s considerable oil wealth to develop the country’s public infrastructure. As its head, Dabaiba played a decisive role, negotiating contracts and overseeing payments to suppliers. But he also had other loyalties; documents show that while on ODAC’s payroll, he ran several companies abroad that benefited from his leading role at the agency.

Dabaiba's embezzlement of ODAC funds did not go unnoticed even during Gaddafi's rule, according to a 2016 book on the Panama Papers leak by two of the journalists who worked on it. The book notes that an advisor to the dictator told Libyan investigators that discrepancies in ODAC’s bookkeeping had been noticed very early on, but were never explored as Gaddafi and his sons were also involved in the agency’s management.

The country’s new rulers proved less willing to turn a blind eye, and Dabaiba’s fortunes changed. In 2012, along with other Libyans holding allegedly stolen assets, he was blacklisted by the Tripoli-based National Transitional Council, the country’s new governing body.

By this point, Dabaiba had fled Libya.

The authorities requested an Interpol red notice in an attempt to apprehend him on charges of embezzlement of public funds, money laundering, abuse of power and corruption, but the document is no longer in force. According to a Libyan news site which cited social media, the Interpol warrant led to his arrest in September 2014. (Interpol would not comment on the reason for its withdrawal, referring reporters back to Libyan authorities, who have also not replied to requests for comment.)

Among the documents obtained by reporters are dozens of invoices issued to ODAC by various companies under Dabaiba’s oversight, showing how he either awarded contracts to those he was affiliated with or might have charged commissions of up to 20 percent on government contracts he negotiated.

The leaked files also contain digital records of at least 16 personal bank accounts Dabaiba held in Cyprus with both Cypriot and foreign banks. They show a portfolio of investments worth millions of US dollars, an amount that is hard to square with what Libyan investigators have said was his official ODAC salary — just £12,000 ($15,600) per year.

In total, the Libyan investigators are looking into more than 100 companies around the world related to Dabaiba, including 65 in the UK, 16 in the British Virgin Islands, 22 in Malta, six in India, and three in Liechtenstein. Libyan authorities have asked law enforcement agencies in all of these jurisdictions for assistance in the investigation.

But it all started in the eastern Mediterranean, in the island nation of Cyprus, where Dabaiba once lived.

Women celebrate the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime in Misrata, Libya. Credit: Youssef Boudlal / Reuters

Women celebrate the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime in Misrata, Libya. Credit: Youssef Boudlal / Reuters

Employer and Employee

Cyprus would have been an attractive location for a Libyan official to set up offshore companies while his own country was under UN sanctions for its role in the 1988 Pan Am bombing. After all, the island offered confidentiality in banking services, had no anti-money laundering framework, and enjoyed a low corporate tax rate.

Dabaiba appears to have used at least seven companies on Cyprus, as well as two in Canada and three in Liechtenstein, to invoice ODAC and to move and invest the stolen funds.

Dabaiba either worked for or owned some of these companies, all of which were linked to an old friend of his who proved a useful partner in crime.

A Libyan businessman named Ahmed Lamlum, an old acquaintance who died in 2014, had helped Dabaiba set up and maintain his offshore empire (as well as sharing in the spoils).

The closeness of their relationship is evinced by the trust Dabaiba appears to have placed in his friend. As Lamlum’s chief accountant once wrote in a 2000 letter to his Credit Suisse bank manager, the Libyan held power of attorney to represent Dabaiba “in his bank accounts” at the Swiss bank.

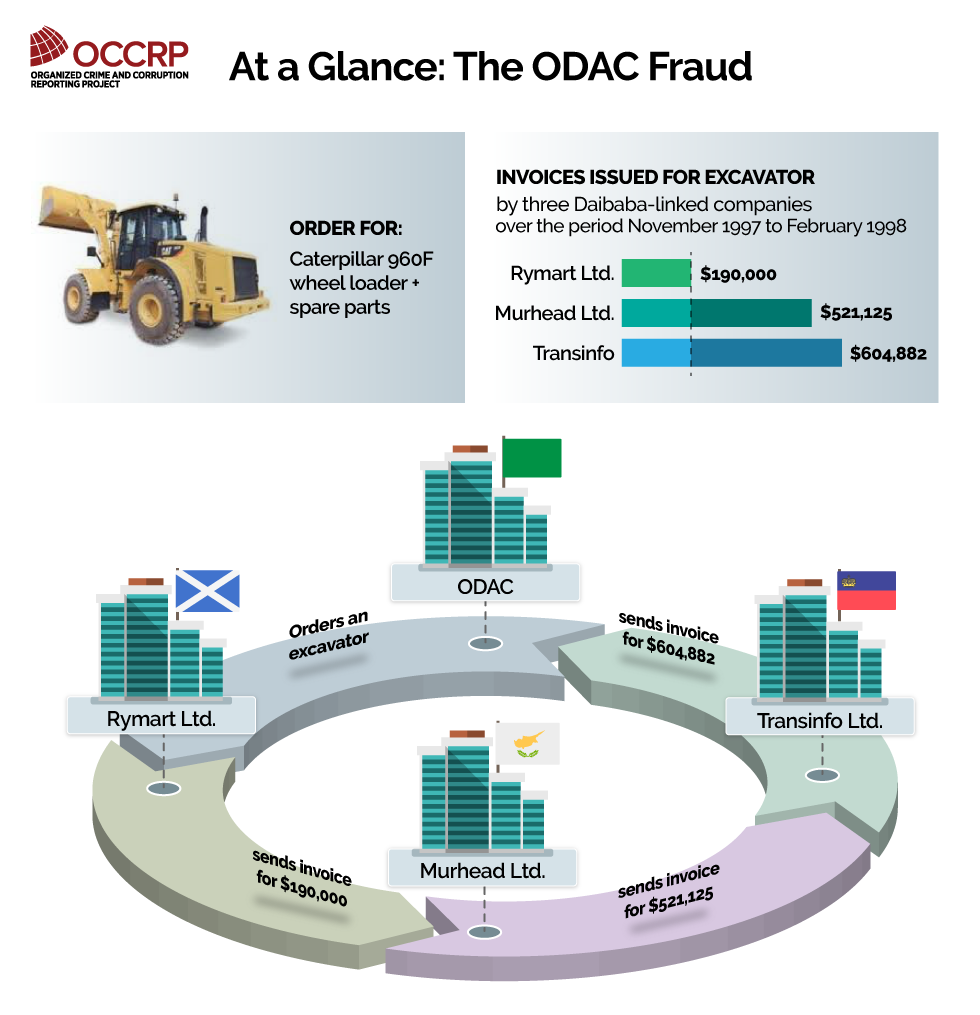

An example of how ODAC helped embezzle Libyan public funds for private profit: in a series of transactions in 1997-1998, Dabaiba-linked contractors invoiced the procurement agency for ever larger amounts of money — all for the purchase of one vehicle. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP Dabaiba and Lamlum shopped for properties in Switzerland together, working with the same real estate agent to purchase two neighboring flats in Montreux on Lake Geneva and even used the same decorator in 1995. In addition to their business partnership, the two even developed family ties. In 1998, Dabaiba’s daughter Amna married Lamlum’s nephew Hani Lamlum.

An example of how ODAC helped embezzle Libyan public funds for private profit: in a series of transactions in 1997-1998, Dabaiba-linked contractors invoiced the procurement agency for ever larger amounts of money — all for the purchase of one vehicle. Click to enlarge. Credit: Edin Pasovic / OCCRP Dabaiba and Lamlum shopped for properties in Switzerland together, working with the same real estate agent to purchase two neighboring flats in Montreux on Lake Geneva and even used the same decorator in 1995. In addition to their business partnership, the two even developed family ties. In 1998, Dabaiba’s daughter Amna married Lamlum’s nephew Hani Lamlum.

One of the companies the two men made use of together — perhaps the most important in their schemes — is the Cyprus-based Fabulon Investments, later renamed to Global Business Network International.

According to its website, this company today specializes in office equipment, office automation, and stationery. But Fabulon was much more than that, playing a key role in the theft of Libyan state funds from ODAC. In addition to receiving a large portion of the money itself, the company acted as the physical headquarters for some of Dabaiba’s other companies.

Lamlum was registered as Fabulon’s beneficial owner, meaning that the company’s profits ultimately accrued to him, at least on paper. As for Dabaiba’s role, the leaked documents variously refer to him as Fabulon’s employee, its head, and also “the sole signatory for most of the company’s bank accounts in Cyprus, Switzerland and England.” A document relating to Fabulon’s bank account at the Cyprus branch of Hellenic Bank gives Dabaiba’s position as the company’s managing director.

Between August 1997 and September 1998, the company submitted at least nine invoices to the Libyan agency for substantial orders of construction materials and furnishings. The total invoiced amount was in excess of $5.4 million.

In 1994, he claimed to be a business consultant of Nuvest Consultancy, another Cyprus-based company.

It’s not known what proportion of these funds may have found their way into Dabaiba’s personal accounts, or whether he received any kickbacks for the ODAC contracts he steered towards Fabulon. (It is known that, even as he earned £12,000 per year from the Libyan agency, he was also pulling at $90,000 from the company as an annual salary.)

The Elias Neocleous & Co. tower in Limassol, Cyprus. Credit: Stelios Orphanides / Sara Farolfi

The Elias Neocleous & Co. tower in Limassol, Cyprus. Credit: Stelios Orphanides / Sara Farolfi

Our Man in Cyprus

In addition to Fabulon — which remains active to this day under the name Global Business Network International — Dabaiba and Lamlum used several other Cypriot companies to obtain and handle their money.

These include Midcon Ltd., Berk Holding Ltd., Olexo Ltd., and Murhead Ltd, all of which either had transactions with ODAC, hid the alleged stolen assets, or both.

One of these companies, Olexo, was used to manage Dabaiba’s assets in real estate, renting out one property in the British county of Surrey for £3,000 per month in 2006. Another property in Surrey generated Berk Holding £3,500 a month. (The properties, which were worth £2 million in 2014, were owned by another Dabaiba-linked offshore).

Documents relating to Olexo provide firm evidence of the close business relationship between Lamlum and Dabaiba — and of the work of the Cypriot agent who helped them make the scheme possible.

On May 27, 2004, Lamlum and his wife, who at that point were Olexo’s ultimate beneficiaries, instructed a local law firm to transfer the 25,000 shares they each held in the company to “Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba or any nominee designated by him.”

Andreas Neocleous & Co, the firm that carried out this service, is one of the largest legal and corporate services providers in Cyprus. Its wealthy, prominent clients have included Dmitry Rybolovlev, a Russian oligarch who had invested heavily in the country’s banking sector.

Andreas Neocleous & Co has a checkered reputation. Its founder, Andreas Neocleous, withdrew from active service after the firm and one of his sons were convicted last year of bribing the country’s Deputy Attorney General, Rikkos Erotokritou, in an unrelated high-profile corruption case. The incident rocked the island’s political establishment, and the firm was replaced by a firm called Elias Neocleous & Co, named after Andreas’s other son.

But the firm had no problem obliging the Lamlums’ request in 2004, transferring their 50,000 Olexa shares to Dabaiba just as requested, which made him the company’s ultimate beneficiary.

Documents in the leak confirm Lamlum’s communications with Neocleous & Co, showing that he had paid the firm for its services and acknowledged receipt of documents relating to the transfer.

The firm also seems to have dealt with Dabaiba himself.

Olexo’s two nominee shareholders remained the same for six years after the share transfer, showing that Neocleous & Co most likely continued to provide corporate services to the company under Dabaiba’s ownership.

Neocleous & Co and affiliated companies also appear to have provided nominee directors and shareholders to the other Dabaiba-linked companies in Cyprus. The companies shared the law firm’s headquarters in Limassol — the Neocleous House — as their postal address. And until he stepped down last November, Andreas Neocleous himself served as the nominee director of Fabulon (now GBNI).

Despite all of the above, when approached by reporters for comment, Kyriaki Stinga, the compliance officer of Elias Neocleous & Co, who also spoke on behalf of the law firm’s predecessor, strongly denied any relationship with Dabaiba.

She flatly denied that it had ever had Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba as a client, but acknowledged that it had offered services to GBNI. She also said that the firm had no record of GBNI being linked to Dabaiba — this despite the fact that he was not only on the company’s payroll, but had access to its corporate account at Hellenic Bank.

In an emailed statement, lawyer Andreas Neocleous said that the law firm he founded had no involvement in the day-to-day running of its clients’ companies nor in their commercial activities. “We should not have expected to be aware of the details of its commercial operations or its trading partners unless there was a legal issue relating to them, such as a bad debt,” he concluded.

Andreas Neocleous added that he could not comment on specific matters related to his clientele, citing the Cypriot advocates’ law, which bans lawyers from sharing confidential information.

However, he did stress that his firm had “acted professionally” and that “nothing came to [its] attention that would have raised any suspicion in the mind of a reasonable person regarding the companies and their stakeholders.” Neocleous added that at the time of most of these companies’ incorporation, today’s know-your-customer and due diligence standards “did not apply.”

“Had our client acceptance procedures disclosed any issues that would have precluded us from acting, we should have declined to act,” he said.

The GBNI offices in Limassol, Cyprus. Credit: Stelios Orphanides / Sara Farolfi

The GBNI offices in Limassol, Cyprus. Credit: Stelios Orphanides / Sara Farolfi

A Friend in Need

But let’s not forget Dabaiba’s close friend Ahmed Lamlum — after all, Dabaiba certainly didn’t.

After Gaddafi was killed and his regime overthrown in 2011, the two men’s previous schemes were no longer possible — Dabaiba was on the run and no longer in a position to secure lucrative contracts. But there is evidence that, in at least one case, Lamlum managed to continue making lucrative deals at the expense of the Libyan state. In 2013, a company under his control sold shelving to a state telecom provider for about €182,000 with the help of a “middleman” who pocketed a 10 percent commission without actually participating in the transaction. Internal correspondence seen by reporters attests to the fact that the price had been artificially inflated to account for the commission.

The late Ahmed Lamlum, a friend and close business partner of Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba. Credit: OCCRP Lamlum’s assets did eventually attract attention in Cyprus.

The late Ahmed Lamlum, a friend and close business partner of Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba. Credit: OCCRP Lamlum’s assets did eventually attract attention in Cyprus.

After Lamlum died in September 2014, Cypriot tax authorities asked the administrators of his property, the Andreas Neocleous & Co’s lawyer Christos Vezouvios and Lamlum’s son Samy, to explain origins of the $2.6 million wired through his bank accounts at two banks on the island between 2008 and 2013.

“As a Cyprus tax resident, [he] is taxed for his global income,” tax officer Tasos Constantinou wrote to Vezouvios and Samy Lamlum in a 2015 letter. “The income of €40,000 to €45,000 per year is insufficient in my view to cover the significant living expenses of the family and the maintenance of the house.”

The house in question may refer to a house Ahmed Lamlum’s widow, Munira Gadour, rents from Dabaiba-linked companies near Limassol. This is confirmed by the source of the leaked documents. It boasts six bedrooms, seven bathrooms, a maid’s quarters, fireplaces, a home cinema, a sauna, a Jacuzzi, heated floors, a gym, a sea view, and a swimming pool. At the time of Constantinou’s letter, it was worth an estimated €3.5 million.

Where The Money Went

A Golden Visa in the Far North

In 1994, Ali Dabaiba applied for a Canadian immigrant visa under the Canadian government’s Golden Visa program, which provides a path to legal residency via investments. His wife and children were included in the application.

Documents show that he invested CA$ 250,000 (US$ 190,000) in government bonds with the Bank of Canada, but his application, which cited Nuvest as his employer, was initially unsuccessful.

As a letter from the Canadian embassy explained, Dabaiba’s earnings were not derived “from investor activity.”

According to one source connected to the investigation, Dabaiba ultimately did obtain a Canadian passport but this could not be verified.

Dabaiba and Lamlum may have exploited the financial system of Cyprus to get the funds out of Libya. But that’s not where they spent most of it.

As it turns out, through their network of shell companies around the world, the duo invested in properties from Canada to Scotland to mainland Europe.

In Canada, Dabaiba and Lamlum set up at least two companies, including the currently inactive Weylands International Trading Inc., established in December 1995.

This company appears to have been a way for the duo to funnel their Libyan money into Canada. Weylands, which was chaired by Lamlum and vice-chaired by Dabaiba, received a CA$ 1 million loan from Transinfo, another Dabaiba company in Liechtenstein that transacted with ODAC. Essentially, he was lending money to himself — and then using it the following year to acquire a CA$ 4.5 million property in Montreal.

Along with his wife, Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba also owns a Montreal flat worth CA$ 628,000 in 2017.

(Weyland paid off in another way, too: In 1997 and 1998, the company invoiced ODAC on several occasions for the sale of tires, medical equipment, and office furniture for over US$ 2.3 million.)

The Dabaiba funds even made their way to the Scottish Highlands. Taymouth Castle is one of Scotland’s most impressive buildings: a neo-Gothic edifice Queen Victoria once visited.

With its own 18-hole golf course, the castle lies on an estate of over 450 acres. Built in 1552, the building, which is regarded as the most important Scottish castle in private hands, stands vacant.

A billboard just outside the front entrance alerts visitors that improvements are on the way, but locals are skeptical.

The castle is a destination for tourists who stroll around the tidy main street and pleasant holiday village of nearby Kenmore. But rather than being admired for its magnificence, it is instead discussed as the “mysterious property at the center of a Libyan money-laundering intrigue,” as one tourist recently told reporters.

Taymouth Castle, Scotland, is just one UK property which is appears linked to Dabaiba’s offshore empire. Credit: Sara Farolfi

Taymouth Castle, Scotland, is just one UK property which is appears linked to Dabaiba’s offshore empire. Credit: Sara Farolfi

Sadly, this is no fairy tale. Along with several other high-end properties in the United Kingdom, Taymouth Castle is suspected to have been among an intricate web of Scottish companies that Dabaiba allegedly used to launder his illicit proceeds.

The allegation, made by the Libyan attorney general, is included in a confidential request for legal assistance sent to the UK authorities in 2014.

The castle may not be the full extent of Dabaiba’s property empire in the United Kingdom.

As reported by the Guardian, companies that appear to be controlled by Dabaiba, his two sons, and his brother have invested in at least six prestigious English properties that have a current value of over £25 million. Furthermore, the Sunday Times recently reported that Ali Dabaiba has amassed a £3 million property empire in Edinburgh.

The asset recovery team working alongside Libyan investigators have also found two high-end German properties in Brandenburg and Berlin that belong to the Dabaibas. Their value is unknown.

These extensive list of properties around the world suggests not only that Ali Ibrahim Dabaiba’s real estate portfolio has continued to thrive since he fled Libya, but that the Lamlum family continues to benefit financially from their long-standing relationship.

Comments And No Comments

The New Indian Connection

The newest developments in the Dabaiba story seem to indicate a continued pursuit of new opportunities for the family's worldwide business empire long after the fall of Gaddafi.

Working since 2013, asset-tracing investigators hired by the Libyan authorities have spotted ten companies linked to Dabaiba in India which are suspected of holding illicitly obtained Libyan state assets.

The revelations about the Dabaibas’ and Lamlums’ operations in Cyprus come at a time when the island is trying to improve an international reputation tarnished by reports of money laundering by Eastern European oligarchs. They appear more than five years after Cyprus agreed, as part of its 2013 bailout agreement with the European Commission, the ECB, and IMF, to introduce stricter anti-money laundering legislation.

MOKAS, the anti-money laundering unit of the Law Office of the Cyprus Attorney General, said via email that Cypriot authorities cannot disclose information about possible suspicious activities reported to them or requests received from third countries, but did add that “further actions are taken,” including liaising with the police, when deemed necessary.

A spokesperson for Hellenic Bank, the local lender with which Dabaiba and Lamlum held both personal and corporate accounts, said that while the bank’s policy bans it from commenting on specific customer transactions, this does not prevent it from taking “the appropriate and necessary action” when there “is even the slightest suspicion regarding money laundering issues.”

The spokesperson added that the lender was cooperating with both regulators and supervisors to minimise the risk of money laundering.

Credit Suisse, where Lamlum had power of attorney to represent Dabaiba, said that it is “committed to operating its business in strict compliance with all the applicable laws, rules and regulations in the markets in which it operates.”

In addition, Andreas Neocleous said that the Central Bank of Cyprus, which was charged with approving foreign investment on the island before it became an EU member, had employed “extensive vetting and enquiries” in all of the investments it had approved, which would have included Dabaiba’s.

“In addition,” he continued, “the approval of the council of ministers was required to undertake certain categories of business and buy premises at the time, and the companies succeeded in obtaining this. Their relations with the relevant government departments were excellent.”

The Lamlums, contacted via GBNI’s general email account and the Neocleous law firm, did not respond to requests for comment. Dabaiba could not be reached for comment.

Family members of the late Ahmed Lamlum still live in Cyprus to this day.

Reporters tried to reach Dabaiba for comment on this story, but were unable to do so.