The twisting Avaz tower that looms over Sarajevo is the headquarters of Fahrudin Radoncic, an intense and dapper former media mogul who is running for president of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

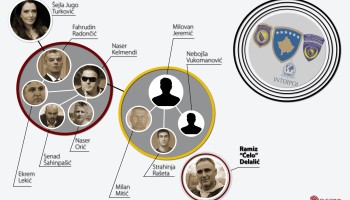

Across the city rises another Radoncic tower, the Radon Plaza Hotel, where according to an indictment from prosecutors in Kosovo, Radoncic met in the spring of 2006 with assorted mobsters to plan the assassination of gangster Ramiz “Celo” Delalic. Prosecutors say the plotters were upset that Delalic was cutting into their criminal profits—and for other reasons.

By the summer of 2007, Delalic was dead, pumped full of bullets one midnight outside a Sarajevo apartment building.

These allegations and others are spelled out in a 49-page indictment assembled by the Special Prosecution Office of the Republic of Kosovo (SPRK) in the curious case of Naser Kelmendi, an ethnic Albanian who has lived for years in Sarajevo yet has spent the past year in jail in Kosovo, a jurisdiction where he is not charged with committing any crimes.

Rumor and business deals have linked Radoncic and Kelmendi for years, but the indictment spells out for the first time the reasons behind those links and states flatly that Radoncic was Kelmendi’s “business partner and political protector” in Sarajevo.

Nonsense, Radoncic insisted in the second of two interviews with OCCRP/CIN. “I met Kelmendi maybe four or five times in my life,” he said; as businesspeople in a small city like Sarajevo, they were bound to run into each other from time to time. He trumpets the fact that he himself was not indicted but only named in the indictment as a member of a criminal organization--which, he says, is not true.

Prosecutors have asked that Kelmendi be kept in custody for fear he will try to flee, intimidate witnesses or destroy evidence. The indictment focuses on two main areas: Delalic’s murder, and what prosecutors say was Kelmendi’s major business from 2000 to 2012 — trafficking large amounts of drugs from Afghanistan and Turkey into Europe.

Kelmendi is expected to stand trial in Kosovo in October—by coincidence, the very month in which Radoncic hopes to win the BiH presidency. Prosecutors say the two are linked by convoluted business interests and criminal activities, including the murder of Delalic, and that it will all be proved at trial.

A major witness in the indictment is Sejla Jugo Turkovic, wife of convicted mobster Zijad Turkovic and a former television journalist who was once Radoncic’s trusted assistant. In an interview with the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and CIN, she gives a detailed account of the meetings and events that led up to Delalic’s death.

“I was involved, I was present at all the events related to Radoncic and Kelmendi,” Turkovic said. She says she knows the details of their various business relationships. And, she says, she knows the roots of the enmity between them and Delalic. “The conflict between Naser Kalmendi and Fahro (Radoncic) with Ramiz Delalic did not happen overnight. It (had) lasted for a long time.”

Radoncic, meanwhile, says Turkovic is simply lying because she is married to a criminal and wants to deflect attention from her husband’s illegal activities.

The indictment names a number of other individuals as members of Kelmendi’s criminal group, and describes their participation in multiple criminal acts. It is unclear why only Kelmendi is facing charges.

Prosecutors have said little about their plans. “The indictment is a full disclosure of the evidence that we have and that needs to be disclosed. The indictment has been filed by SPRK, and with that we will move forward with commencement of the case as soon as the court advises us of those dates,” said Jonathan Ratel, deputy chief prosecutor with SPRK.

Radoncic, on the other hand, had several things to say. “Sejla Turkovic put forward a number of lies” about the Radon Plaza meetings and alleged murder plot, Radoncic told OCCRP/CIN in the first interview in his Avaz tower office. Radoncic seemed agitated as he spoke, moving around restlessly and stabbing the air with a presentation pointer when he wanted to emphasize a point.

“Sejla Jugo Turkovic is the wife and close associate of Zijad Turkovic, the leader of the biggest criminal organization in the history of BiH,” he said. Why, he asks, was she “not prosecuted for her participation or assistance in the criminal activities of this criminal organization?”

Turkovic’s husband was convicted last year and sentenced to 40 years on organized crime charges, including murder, narcotics smuggling, extortion, and money laundering; the appeals court overturned that verdict last month and ordered a new trial, although Zijad Turkovic remains in detention.

Radoncic said Turkovic must have witnessed many criminal activities, living with her husband, and yet she faces no charges. Most probably, he said, she was promised “that she would not be prosecuted if she gives false testimony against me.”

So what exactly is she saying?

According to the indictment, Radoncic and Kelmendi were not alone as they discussed Delalic’s fate in the Radon Plaza’s iconic revolving restaurant. The indictment says the meetings were also attended by “Ekrem Lekic, Sarajevo businessman Senad Sahinpasic and Naser Oric.”

According to Turkovic, the restaurant was their regular meeting place. “All the meetings took place there,” she said. “Kelmendi regularly came, as if he was in his own house, as a host. That is how they behaved with him, waiters, staff and Avaz journalists and everyone.”

The others involved confirm part of her story but say she was wrong on all of the important points.

Lekic told OCCRP/CIN that he was indeed part of a group that met nearly every day at the restaurant. He and Radoncic were lifelong friends, he says, stemming from before the war, when both were journalists covering dangerous stories.

Turkovic says the group met to discuss what to do about Delalic, an organized crime figure who was publicly denouncing Kelmendi as a drug dealer and accusing other rival crime figures of unsavory activities during the war years.

Nonsense, said Lekic. “I used to work out every day” in the gym at the Radon Plaza, and then would have coffee with a group of regulars, he said. He said Turkovic was lying about the group and what they discussed, and noted that although Delalic was killed in 2007, Turkovic never talked to the police about it until 2011.

If she was telling the truth, he said, “why did she wait four years?”

Turkovic says the members of the group had different reasons to be annoyed with Delalic and that those reasons evolved over time. For Radoncic and Kelmendi, it was primarily economic: they were worried that Delalic’s denunciations would cut into Kelmendi’s drug business and cost him money.

Prosecutors believe that for Lekic, it became personal in the spring of 2007, when his relative Selver was murdered, and that he believed Delalic was responsible. Not true, Lekic says; Selver Lekic’s death was just one of those things.

“It was a drunken story, it happened late at night, if he were not in that café he would not have been killed,” he told OCCRP/CIN. “There was a quarrel and this one approached him and shot him in the head. That young man did not even know Selver.” He was equally dismissive of the idea that Radoncic would want to avenge his close friend’s death. “So what, is that supposed to be some motive?”

The motives of Sahinpasic and Oric are less clear. According to Turkovic, Sahinpasic was a close political ally of Radoncic. In a brief interview with OCCRP/CIN, Sahinpasic said he was a lifelong friend of Radoncic but that nothing Turkovic said was true.

“I don’t know what she is talking about,” he said. “You’ll have to ask her.”

Oric is considered a local war hero in Srebrenica for his defense of Muslims during the war. He was an officer in the Bosnian Army and was charged with killing Serb civilians; after his 2006 conviction for war crimes at The Hague, he was sentenced to two years in prison but later cleared of all charges on appeal.

Turkovic said Oric was an enforcer for Kelmendi. “He had to do everything that Kelmendi wanted because he worked for him, and that is how he made a lot of money,” Turkovic says.

Contacted by phone by OCCRP/CIN, Oric declined to comment, saying this case had caused a great deal of trouble in his life and he did not want to say anything.

According to the indictment, Radoncic had other reasons to dislike Delalic.

“Radoncic hated Ramiz Delalic for a number of personal reasons. Radoncic’s wife had been in a relationship with Delalic during the war, before she got married to Radoncic—a circumstance which Delalic used to brag about.”

That claim is “false and stupid,” said Radoncic, noting that the relationship was more than 20 years in the past “and before her marriage to me!? It is stupid for someone to be jealous of such things, and anyway, it isn’t true that my ex-wife was in a relationship with Ramiz Delalic!”

Turkovic’s story about what transpired in the revolving restaurant dovetails with events described in the indictment, although she provides more details. For example, she says the group had trouble finding someone to hire to kill Delalic, with their first few choices—including the man who would become her husband--turning them down.

But eventually they decided on a plan. The indictment states that Kelmendi volunteered to travel to Serbia to hire some killers for either 200,000 KM (US$ 144,000) or € 200,000 (US$ 272,000) . Turkovic said these were people who had worked for Kelmendi before.

At a meeting near the end of May 2007, Kelmendi arrived with a small black suitcase, saying he and Oric had brought their share of the money to hire the hit men. Lekic handed a small Samsonite shoulder bag to Kelmendi, who “took a large amount of money from the bag, putting it into his suitcase.”

Radoncic “took money out of a green PVC bag and gave it to Kelmendi, who added also this money to his suitcase,” the indictment states.

Kelmendi later reported that he had given the money in Serbia to a man nicknamed “Krce”, later identified as Milovan Jeremic, “in order for two well-known Serbian hit men, Milan Mitic and Strahinja Raseta, to be hired to murder Ramiz Delalic.” A third man, Nebojsa “Cetnik” Vukomanovic was also hired, the indictment alleges.

On June 27, Delalic was shot to death in Sarajevo.

The indictment goes into some detail on how it all happened:

Prior to the killing, Kelmendi left Bosnia to visit the seaside in Montenegro, to establish an alibi.

Oric was responsible for tracking Delalic’s movements, including his visits to an apartment on Odobasina Street in the center of Sarajevo.

Delalic died at the foot of an outside staircase leading to his girlfriend’s apartment at 1a Odobasina St. He had been shot 10 times with handguns, a .357 Magnum and a 9 mm Heckler & Koch. A silencer was found under a nearby car. Evidence at the scene told police someone—later identified as Raseta—had crouched under the staircase and waited for Delalic to arrive.

Witnesses later testified that as Delalic was approaching, Vukomanovic whistled to Raseta to warn him to get ready.

“Since Delalic was a big man, (Raseta) emptied the entire 27 rounds of the Heckler & Koch at his victim, and because Delalic still was not dead, (he) then shot him several more times with the (.357 Magnum).”

Turkovic told prosecutors she got an SMS from Radoncic that night, telling her Delalic had been killed, which she took as a warning to say nothing to police.

Witnesses said the alleged assassins went back to Serbia and a few days later, Raseta received € 100,000 (US$ 136,000); Vukomanovic got € 20,000 (US$ 27,000) and an Alfa Romeo.

According to the indictment, in the aftermath of the murder, Kelmendi met with his co-conspirators to “discuss how to divert the murder investigation towards other persons.” The indictment says the group felt “empowered” by having successfully pulled it off.

In her interview, Turkovic described a meeting after the murder, but it isn’t clear whether it is the same one discussed in the indictment. What is clear is that the conversation quickly became frightening.

“After the murder they met, I don’t know how long after, whether it was two or three days after, but it was being decided to do something else, one more murder, to kill Fikret Kajevic,” she told OCCRP/CINS. “Because he was designated as the successor to Ramiz Delalic.”

Turkovic said she argued against it, telling the group that the two men were not close and that Kajevic wouldn’t want to take over anyway.

“Kelmendi threw a newspaper at me, with a picture of Kajevic in a shirt with Ramiz’s face, and I think that he was lowering Ramiz’s coffin in the ground, and he threw that in front of me and said, ‘Really? They don’t speak with one another? He won’t be his successor, but he is in the front row!’ And he told me that really harshly. He angrily threw the paper at me.”

Turkovic said that as she argued against the idea of more murders, she began feeling isolated. She says she knows Radoncic so well that “when I look into his eyes, I know what he is thinking.” She said he looked at her piercingly, as if he doubted he could trust her any longer. .

“As if he was scared that I would now do something, that I would turn them in, that I would do something stupid, break down.”