Naser Kelmendi likes to portray himself as a simple, self-made businessman who owned a few nice properties and an ice cream factory, with some friends in high places in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

But according to the 49-page indictment issued by the Special Prosecution Office of the Republic of Kosovo (SPRK), he is a major drug dealer who made millions between 2000 and 2012, moving heroin, Ecstasy, speed and other drugs through a network that linked Afghanistan, Turkey and the European Union.

Seven of the indictment’s nine counts deal with Kelmendi’s drug operation. Prosecutors say that it was effective, and that their investigation “reveals he and his sons possess millions of Euros in assets in Bosnia, Montenegro, Kosovo and elsewhere.”

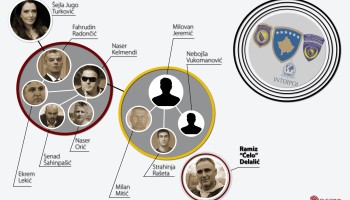

The other two counts accuse Kelmendi of plotting with other members of his organized crime group—including former BiH Minister of Security and current presidential candidate Fahrudin Radoncic — to murder rival mobster Ramiz “Celo” Delalic in 2007.

Kelmendi has been jailed in Kosovo for more than a year awaiting trial, which is expected to begin in October, the same month in which Radoncic hopes to be elected president of BiH. Prosecutors have asked that Kelmendi be held to prevent him from fleeing, tampering with witnesses or destroying evidence.

The indictment lays out a wide-ranging series of events involving dozens of people spanning multiple continents and more than a decade, with participants showing both innovation and creativity in solving the myriad problems that can crop up in moving large amounts of contraband between countries.

For example, Count 3 addresses events as far back as 2000, when witnesses said they knew already that Kelmendi “was a person with (an) enormous amount of money” who could provide them with pure heroin. Prosecutors describe Kelmendi in this count as “an extremely careful person … at the top of (the) drug smuggling pyramid and of other criminal activities in the Balkan region and even beyond.”

Kelmendi’s son, Besnik, 31, dismisses the allegations, telling OCCRP/CIN that his father has nothing to do with the drug trade and is instead being persecuted for political reasons by BiH President Bakir Izetbegovic, a rival of Kelmendi’s friend Radoncic.

That’s how Kelmendi ended up blacklisted by the United States as a drug trafficker, his son says. “Believe me, this is all a political game. What does Naser have to do with politics?”

The indictment, however, cites detailed testimony from a number of witnesses—some named, and some identified only as “K1” through “K5”, who say they worked directly with Kelmendi in dozens of significant drug deals over the years.

A witness identified as “K3,” a “high-level Belgrade drug dealer,” said Kelmendi’s rise began “after the Belgrade-based crime syndicate called the Zemun clan was dismantled following the killing of Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic in 2003.” K3 said Kelmendi’s career got another boost when Montenegro broke away from Serbia in 2006, “which gave Kelmendi a sudden monopoly over the drug and also the cigarette smuggling market there.”

By 2009, K3 said he was buying between 1-4 kilos of heroin and Ecstasy per month, as well as unspecified amounts of cocaine, speed and marijuana in a business relationship with the Kelmendi organization which lasted until October 2012.

Another witness identified as “K1” said he started selling drugs for Kelmendi in 1996, when Kelmendi was already importing Afghani heroin through Turkey into Kosovo, BiH, Montenegro, Austria, Switzerland “and other European countries.” K1 said “huge amounts” of mostly white heroin and Ecstasy moved from Turkey into western Europe.

The Kelmendi group was resourceful when it came to the actual smuggling, according to the indictment. They stuffed drugs into hollow plywood tables and doors, hid them in truckloads of lemons and shipments of textiles. Shipments might be hidden in as many as 10 trucks at a time.

And it was good stuff, top quality heroin that was “much stronger than usual”. “Users told K3 that the regular heroin would give them a kick, while the white heroin would knock them out,” the indictment states. Smugglers brought in up to 100 kilos at a time through mountainous border regions.

Ecstasy, in pill form, received different treatment. The indictment says the group would get shipments of up to 200,000 tablets from Holland packed in plastic bottles holding up to 4,000 tablets each. The bottles would then be wrapped in white Teflon tape before being packed into specially modified gas tanks; as many as five drivers per day would set off from Holland to destinations across Europe.

Smaller shipments might be transported in cars, either in gas tanks, inside the roof or in specially built compartments, while larger ones went into the gas tanks of big trucks or in secret pockets sewn into truck tarpaulins. The indictment also says the group used small amounts of money, transferred via Western Union from Kosovo to Turkey, to signal when a drug shipment had been successfully received.

The indictment also lists extensive cryptic SMS exchanges between group members, signaling when a particular shipment had crossed certain borders.

It further delves into the financial records of the Kelmendi family, including paperwork confiscated from the family home in Peja, Kosovo on Dec. 13, 2013, showing “transactions involving hundreds of thousands of US dollars and Euros.”

Witnesses told investigators Kelmendi “was making ‘billions, millions’ from his drug trafficking organization; one noted that Kelmendi had been able to give his son, Elvis, € 5 million (US$ 6.6 million) to start a business, in addition to apartments in Sarajevo.

But it is not clear where all the money went. After an exhaustive listing of bank accounts, transactions and property tax records, the indictment sums up the traceable money linked to the family between 2001 and 2013 as € 4,412,406 (US$ 5.8 million).

The indictment then goes on to examine individual deals, some dating back to Kelmendi’s early years in BiH.

Besnik Kelmendi says his father came to BiH in 1988 to open a leather goods store in Skenderija, at that time a cultural and sport center in Sarajevo. Driven out by the war, he returned from Kosovo after its end and “worked here as a trader, with leather, clothes and the like,” he says.

The indictment describes a somewhat different chain of events.

A witness identified only as “K2” alleges that Kelmendi first approached him in Montenegro, when K2 was a gun smuggler for the Kosovo Liberation Army, and offered him a job driving heroin to England. K2 declined the offer, but Kelmendi persisted in his offers of employment.

In 2000 in Kosovo and later in Turkey, Kelmendi asked K2 to organize a hit on a man who had cheated Kelmendi by not paying for 100 kilos of heroin. K2 declined, but later heard that a man named Muzafer Kalic got killed in Bosnia, and that he was the man who had failed to pay for the heroin.