When senior Rome customs official Concetta Anna Di Pietro received a call from her colleague in Milan telling her that British American Tobacco had put out unauthorized signs advertising its cigarette prices as “locked in” at current rates — unlike their competitors’ –— she flew into a rage.

Di Pietro’s anger was captured in wiretaps made by police, who arrested her in December 2019 over allegations that she colluded with Philip Morris, the main rival of British American Tobacco (BAT) in Italy. She was accused of leaking confidential information and delaying announcements on changes in tax rates to give Philip Morris an edge in making pricing decisions.

The signage sent her into a spin not only because it was illegal, but because it advertised that BAT was keeping its prices the same — just days after it was announced that Philip Morris would increase the cost of its cigarettes. Customs officials, who police say were being bribed by a senior Philip Morris executive in Italy, went so far as to order raids on tobacconists who carried the advertisements in Milan, Rome, Naples, and Florence.

Soon after receiving the call from Milan, Di Pietro spoke to Fabio Carducci, another customs official in Rome, and told him the bosses were livid about the advertisement. “What the fuck have they started?” she asked. “The tobacconists mustn’t use those signs.”

Then she called Fabio Pacella, a customs director for the region of Lombardy, which covers Milan, and demanded he punish the shops displaying BAT’s unauthorized ads.

“You must break the tobacconists,” she ordered him, according to a police transcript.

The episode, from March 2018, is detailed in months of secret wiretaps by Italy’s state police that appear to reveal the corrupt quid pro quo between several customs officials, including Di Pietro, and a senior Philip Morris executive in Italy at the time, Leo Checcaglini.

They also appear to show how Philip Morris compromised a new system implemented in the EU last year to try to curb cigarette smuggling. Evidence collected by OCCRP shows that the tobacco company not only targeted the customs authorities tasked with implementing part of the system in Italy, but also has close ties to a company that is overseeing Philip Morris’ production lines.

Police in December 2019 arrested nine people, including Di Pietro and other customs officials, as well as Checcaglini. Police confirmed that Di Pietro, her boss Massimo Pietrangeli, and Checcaglini were all released between January and late February after serving less than three months each under house arrest.

Among other allegations, customs officials are accused of delaying a planned tax increase upon request from Philip Morris, which theoretically could have allowed the company to import thousands of packs of cigarettes before the new tax regime was imposed. While the wiretaps do not reveal exactly what Philip Morris did with the information, police say Checcaglini deemed it valuable enough to offer informants favors, promotions, and plum jobs at other companies in return.

Checcaglini allegedly helped Di Pietro, whom he affectionately called Annarella, by providing free accommodation to one of her friends for six months. Checcaglini also offered to get her boss, Pietrangeli, promoted to Central Director of Excises and Tobacco Monopoly — a role in which he would have been able to favor Philip Morris when setting cigarette prices.

The relationship between Checcaglini and Pietrangeli, who police say met once a week at the customs office in Rome’s lively Trastevere neighborhood, even seems to border on jovial. In one of their wiretapped conversations, Pietrangeli refers to BAT as “battoni,” playing on the company’s name to turn it into a vulgar Italian word for prostitutes.

The customs case erupted into the open in Italy last month, when BAT reportedly filed a complaint with Rome’s prosecutor alleging that Philip Morris’ “corrupt system” within Italian customs had distorted the country’s cigarette market and created unfair competition. The release drew an angry retort from Philip Morris within hours.

COMMENTS ON THE CASE

Here’s what Philip Morris and Italian customs had to say about the case, and tobacco track and trace:

‘Entirely Italian’

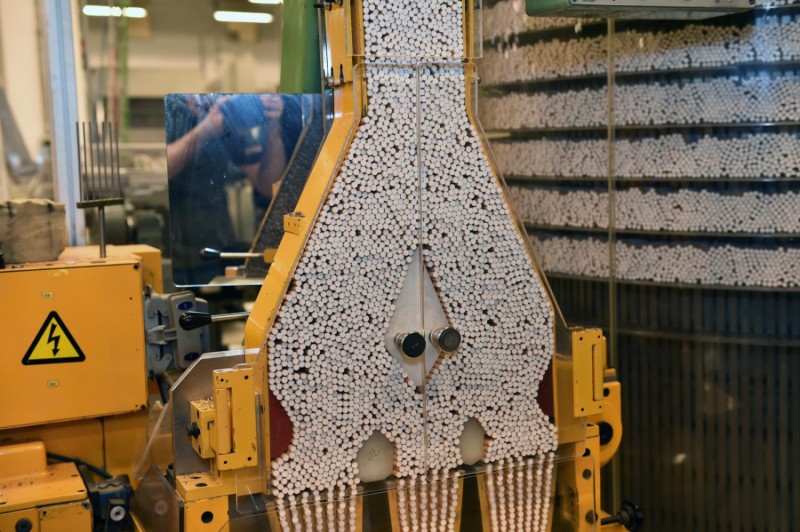

For years the EU wrestled with the best way to combat rampant tobacco smuggling, which costs the bloc an estimated 10 billion euros ($11 billion) a year in lost taxes. In 2014, it passed the Tobacco Products Directive, a range of restrictions on how tobacco can be sold and traded in the bloc that includes forcing member states to install track-and-trace systems to monitor cigarette production.

The rules require that governments retain control of key parts of the system to ensure they are not compromised: the ID codes printed on every packet and the central repository that stores data on them. Some parts can be subcontracted out, but only to companies that are independent from the tobacco industry.

OCCRP’s findings call that independence into question in Italy.

Officials in customs authorities who are meant to ensure the ID system remains independent from the tobacco industry are accused of colluding with Philip Morris. And a company with a close relationship with Philip Morris, called Fata Logistic Systems, helped develop track-and-trace software and reportedly continues to provide logistics support to the tobacco giant.

In one wiretapped conversation from February 2018, Checcaglini and Pietrangeli even discuss “traceability,” implying that track and trace would be less difficult to manipulate to Philip Morris’ advantage than other aspects of Italy’s complex tobacco regulation system.

Fata Logistic Systems has an office inside the Philip Morris Manufacturing and Technology building, in the city of Crespellano, near Bologna in northern Italy. The company is licensed by customs in Crespellano to deal with tobacco products, and police say it distributes cigarettes from Philip Morris’ warehouses to retailers.

Checcaglini showed just how close their relationship was when he allegedly set up a job interview for Di Pietro’s nephew at Fata Logistic Systems in return for her help postponing a price increase, according to a police report. (He ultimately could not move forward in the recruitment process due to issues with his previous job.)

Fata Logistic Systems also worked directly with Philip Morris to build a controversial piece of track-and-trace software called Codentify. Philip Morris developed the software in 2004 as part of an approximately $1.25 billion anti-smuggling settlement with the EU, and worked alongside rival companies to peddle it to governments, despite concerns that it is ineffective and too close to the tobacco industry.

Fabrizio Viviani, a former IT security, network, and domain administrator with Fata Logistic Systems, said he worked with Philip Morris and Italy’s financial police to further develop Codentify software around 2014. He told OCCRP that as far as he knew, the project, which he worked on in a previous role, was entirely Italian.

Italy’s financial police, the Guardia di Finanza, confirmed they had signed a memorandum of understanding with Philip Morris in 2014 to help fight tobacco smuggling and counterfeiting, but said they were not involved in developing Codentify.

Customs said Fata Logistic Systems, “acting on behalf of the Association of the main cigarette suppliers in Italy,” had provided Codentify technology for a trial track-and-trace system in 2012. That project was abandoned, however, after the EU brought in new rules in 2014 mandating that the state oversee key aspects of track and trace.

Fata Logistic Systems has also advocated for an even larger role for the tobacco industry in the EU’s track-and-trace system. In a submission during the bloc’s consultation on track and trace, it backed an “industry-operated solution” in which tobacco manufacturers would be responsible for adding ID markings to tobacco products.

A person close to the process, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media, said Fata Logistic Systems’ submission reproduced a text from the tobacco industry, almost word-for-word. (A representative of Fata said the company was unable to comment, citing the coronavirus crisis in Italy.)

As it stands, experts say it is unclear how effective the EU’s track-and-trace system will be. But Italy — with its high profit margins on cigarettes and potentially corrupt officials — will remain a haven for the world’s largest tobacco companies, according to Silvano Gallus, head of the Lifestyle Epidemiology laboratory at the Mario Negri Institute for Pharmaceutical Research in Milan.

“Italy is a paradise” for tobacco companies, he said.