Last September, two dozen people filed into a new glass and steel tower office building in Palladium City, not far from downtown Kyiv. They looked like accountants or executives entering the eighth-floor office of what seemed to be one of the few occupied suites in the building. An employee greeted them, collected $140 cash from each and ushered them into a large room that filled quickly.

A smartly dressed women in her 30s strode to the front.

“How many people here already own an offshore company?” asked, Ivanna Pylypiuk, managing partner of International Consulting Group (ICG). There was silence. “You don’t want to admit it,” Pylypiuk said smiling. Participants did not introduce themselves; forms were distributed so that questions could be asked confidentially. The entire seminar was geared to anonymity.

Pylypiuk was the first of a number of speakers over the next few hours who explained how to set up offshore companies – a tool increasingly being used by organized crime, corrupt politicians and businessmen to avoid taxes, launder money and to hide their assets.

The training, titled “The Offshore Schemes in Business: Everything Important You Need to Know Working with Offshores - Practical Advice,” was also attended by a reporter for the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). It was advertised as a seminar where participants could learn how to minimize corporate and personal taxes and hide money or assets offshore. Such seminars occur in Kyiv and other big cities of Ukraine as often as once a week.

According to the seminar package, it was jointly organized by ICG, Tax Consulting UK, and Aurora Consulting. In Ukraine, taxes are not only expensive, but complicated. A World Bank report in 2010 called Ukraine’s tax system the third most difficult in the world behind only Venezuela and Belarus.

Pylypiuk told participants that the offshore schemes she and her colleagues were presenting could be purchased after the seminar. “Each one of you has the right to a free personal consulting session,” she told them.

Learning To Hide

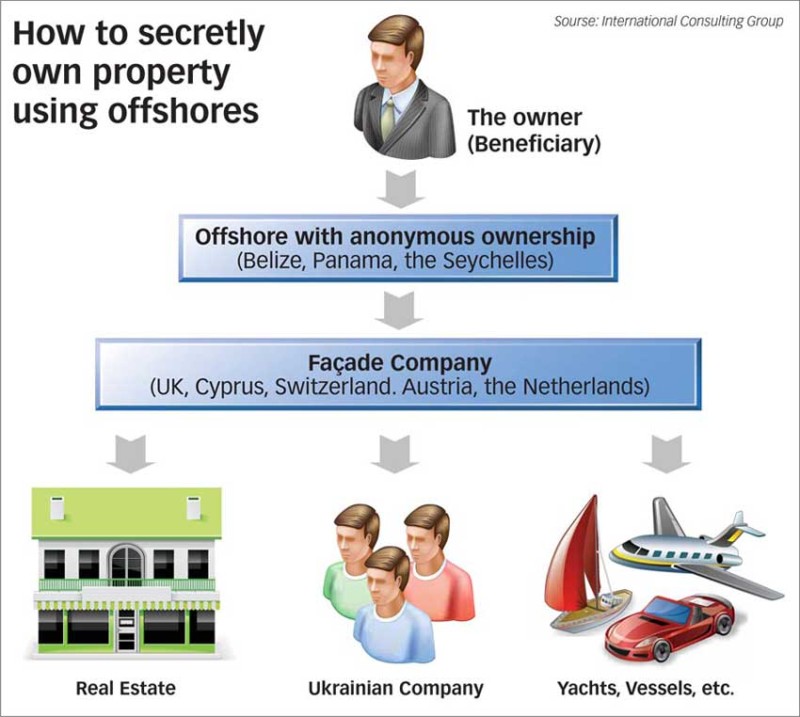

The seminar delivered as advertised, revealing tricks of the offshore trade while scrupulously avoiding much discussion of what may be breaking the law. Pylypiuk and others offered helpful advice such as: those involved in export and import operations have the most to gain in avoiding taxes. And that offshores were good for the wealthy especially those with yachts and other high-end assets. “Beware of the political instability and the new tax code, with its luxury tax,” she told participants. Speakers recommended that Ukrainians open companies in locales such as Belize, Panama, and the Seychelles and combine them with fake fronts in the UK, Cyprus or Holland.

A middle-aged woman in the front row interrupted Pylypiuk to ask how she could money from Ukraine to the account of her offshore company.

Pylypiuk seemed amused. “The offshore can accept any amount of money - transferred from a Ukrainian company’s account, another offshore company’s account, or even from a suitcase of cash that you have, because the offshore company doesn’t have to report. There are lots of schemes, but I can only tell you the details in private, as cash transactions would be a criminal offense,” she replied.

Speakers were vague on details, promising students help later in private. But they assured it could be as simple as “an easy wave of your hand and the money is transferred to your [offshore] account”. “As long as you have the money in the first place, the rest would be easy,” Pyplypiuk said.

The audience had questions about tax evasion too.

“If I have a supermarket chain, what’s the best way to import vegetables?” asked a participant. The answer drawn on a whiteboard was a classic offshore scheme. A company in the European Union (EU) acts as façade for a series of offshore companies connected to a licensed warehouse in Poland used for the importation.

“Offshore is the place where all the traces and connections disappear. The only authority that can get through to an offshore company with requests is Interpol, but you will be the one who will be responding to their request,” said Viktoria Boyko of Tax Consulting UK/Aurora Consulting.

During the lunch break, the lecturers get to know the students better, chatting with them over coffee. Soon, however, the conversations got into specifics. A lecturer asked how much cash a participant needed to transfer and promised services to help.

The OCCRP reporter talked with speaker Iryna Nesterenko, a lawyer with ICG. He asked how he could avoid paying taxes on a consulting services contract with a US company. “It’s possible,” - Nesterenko replied, but difficult and expensive.

Offshore Transparency

According to Ukraine’s State Tax Administration, offshore-related activities are on the rise. The first half of 2010 has seen a 54 percent growth in exports to offshore companies, totaling $1.6 billion. The most popular offshore destination, according to the tax authorities, is the British Virgin Islands, which accounts for 73 percent of offshore trade and almost 5 percent of all trade.

Yaroslav Lomakin is the founder of the Honest & Bright, a Moscow consulting firm and former head of the Kiev branch of Tax Consulting UK, a UK registered firm that co-sponsored the conference. He has watched the offshore services segment grow in Ukraine as well as in Russia.

“I don’t know a single big business in Ukraine which is owned transparently and doesn’t use non-resident companies,” he said.

Lomakin’s description of Ukraine’s business climate is well illustrated by the statistics. According to the State Statistics Committee, Cyprus is the top foreign investor in Ukraine, having invested more than $9 billion, or 22.5 percent of all the foreign investment. Cyprus also is the biggest recipient of foreign investment from Ukraine. Local companies invested $6.3 billion in the island country, or more than 93 percent of outgoing investment.

Martin Raiser, the World Bank director for Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova, says there is no precise calculations how much tax revenue is lost in Ukraine due to the widespread use of tax minimization and evasion schemes.

However, Raiser points out that in Russia, the elimination of the double-taxation agreement with Cyprus alone increased tax revenues by about 0.6 percent of gross domestic product, or nearly $7.5 billion.

According to expert estimates, in Ukraine the revenue lost because of the double taxation agreement with Cyprus could reach up to $ 3 billion a year – nearly 10 percent of the government’s approximate $30 billion in spending annually.

Closing tax loopholes is one of the crucial suggestions made by the World Bank in its recent Country Economic Memorandum.

“The point of closing these loopholes is not only to decrease the budget deficit, but also to make the big businesses benefitting from the offshore loopholes contribute to fiscal adjustment,” Raiser said, adding that most of the big businesses in Ukraine are using offshore minimization schemes, because they are currently legal.

Lomakin adds that with Ukraine’s high taxes and corrupt business environment, only the political elite can get a break for their companies. Everyone else must use offshore companies.

Beneficiaries of the boom is the offshore services industry, which, he said, has become so sophisticated that it can easily adapt to attempts legislators might make to stop the tax minimization and evasion schemes. Lomakin estimates that a company that specializes in selling and servicing offshore companies can earn from $2-$10 million annually. At the same time, Lomakin doubts tax authorities can or will do anything.

“The worst thing could happen, when they go to the office of such a consulting company and ’torture’ you to find out who bought a specific offshore, all they would get would be the name of a lawyer or some other intermediary,” said Lomakin. Besides, he adds, corrupt officials very often use the same schemes to siphon their own illegal incomes out of the country.

“They would not be cutting the tree branch they are sitting on,” he laughs.

OCCRP talked to Pylypiuk a few months after the seminar. She said her company is doing nothing illegal. It’s up to clients how they use the information it dispenses. She said that the tax authorities are aware of most of what they present -- so there is no guarantee that they will always work. She denied her company would assist in moving a client’s cash offshore.

Lomakin, a former top manager of co-organizer Tax Consulting UK, claimed the same thing. “Moving cash is purely criminal. I stay away from these clients; they stink. There are a million beautiful and legal ways of moving 1 million out of the country,” he said.

Both Aurora Consulting and Tax Consulting UK are linked to Dmytro Cherniavsky, a 39-year-old Ukrainian-Russian businessman and a former state official referred to as the board chairman of Aurora. According to the news report on the official website of Ukrainian government, Russian Aurora Capital that he heads was registered as a daughter company of the Danish Holding Aurora Investment. Starting in 2003, Chernyavsky’s was the vice-president for Eastern Europe for Tax Consulting UK.

A database of Ukrainian companies from 2008 shows that the Ukrainian representative office of Tax Consulting UK is registered at Kyiv’s downtown Shota Rustaveli Street, 24 office 19, while the office of Aurora Consulting is located in office 17 of the same building. Both companies use the same phone number.

In October of 2008, Chernyavsky was appointed interim director of Kyiv’s Olympic soccer stadium, which is undergoing reconstruction that will cost the government an estimated $500 million. The stadium will be the venue for the Euro-2012 final match. The announcement of the appointment of Chernyavsky on a government website praised his corporate governance skills and experience, mentioning his involvement with Tax Consulting UK.

But in May 2010, Chernyavsky was in charge when the Prosecutor General suspected said the organization gave out a contract worth $70,000 for consulting that had been done and paid for already. Earlier, the parliamentary commission investigating reconstruction of the stadium established that during the currency exchange operations under Chernyavsky’s management, losses incurred by the state totaled 543,000.

Yet, no charges were ever filed. In July, he married Ekaterina Bogoliubova, a daughter of Gennady Bohoiliubov, Ukraine’s third richest man, whose wealth is estimated by Korrespondent magazine at $6.3 billion.