What do an 81-year-old grandmother, a millionaire lawyer, and a waste treatment tycoon have in common? They have each been investigated as part of corruption, money laundering, or fraud probes in Brazil, where they are closely connected to the political elite.

Reporters have now found another link between these well-to-do Brazilians: They all own companies in Luxembourg, a tiny western European nation with secretive financial regulations.

Inês Maria Neves Faria is the mother of Aécio Neves, a prominent Brazilian politician and father of three who is at the center of multiple corruption investigations. She has mostly stayed in the background while her son’s political career soared, but Luxembourg’s company registry suggests she might have played a part in building his financial empire.

"The public prosecutor should investigate the material you found, and add it to the [criminal] complaint that has been made," said Claudio Fonteles, a former federal prosecutor general.

Some of the firms could also play into two other investigations.

A close ally of President Jair Bolsonaro, Luís Felipe Belmonte is a wealthy lawyer who has funded political candidates from a variety of parties. He owes US$1.8 million in taxes, has been investigated for money laundering –– and admitted to journalists that he has not declared to authorities that he owns a company in Luxembourg.

Carlos Leal Villa, meanwhile, was accused of being personally responsible for a social and environmental catastrophe caused by subsidiaries of his Solví Group, which had failed to properly dispose of toxic chemicals and sewage from the city of Belém. Brazilian prosecutors, however, struggled to hold him accountable.

Four Solví Group firms implicated in the landfill scandal are ultimately owned by a complex network of holding companies Leal Villa set up in Luxembourg, OCCRP has found.

Luxembourg has long been an attractive destination for people around the world who want to hide their wealth. But in 2019, the country responded to European Union requirements for transparency by making public a registry of people behind companies hosted there.

The initiative was limited by the fact that the public registry can only be searched using the name of the company, and not the name of the owner.

To get around this, French newspaper Le Monde managed to scrape 3.3 million records from the register’s online platform, then collaborated with OCCRP’s data team to make them searchable. This allowed journalists to trace some of the firms connected to Brazilian elites.

Inês Maria and Aecio Neves, with Antonio Anastasia, at a political event in October 2011.

Selling Influence

Congressman Aécio Neves has been the subject of multiple corruption probes, but investigators have never before tied his wealth to Luxembourg.

Allegations of corruption have dampened the career of the high-flying politician, who came second in Brazil’s 2014 presidential race. Prosecutors allege he set up a sophisticated scheme for receiving dirty money, involving foreign bank accounts and companies.

Neves was caught on tape allegedly arranging to take bribes from Joesley Batista, a powerful businessman who collaborated with the Federal Prosecution Service. Batista told prosecutors that he had made about $47 million in payments to Neves, who allegedly used his political influence to secure tax breaks for Batista’s companies.

Batista told prosecutors that in 2017, both Neves and his sister, at different times, told him to buy their mother’s duplex apartment in São Conrado, an upscale beachfront neighborhood in Rio de Janeiro, for 40 million Brazilian reals (about $12 million). This was almost twice its listed value, according to a report by Brazilian TV station Rede Globo’s flagship news program, Fantástico.

Now, the OpenLux data reveals that Neves’ mother, Inês Maria Neves Faria, owned a company in Luxembourg. The firm, Domomedia Investment Holding, was created in 2017, just 17 days before Neves’s sister asked Batista to overpay for her mother’s apartment. However, Inês Maria Neves does not appear in company documents until the following year.

Domomedia has never been mentioned by prosecutors, who have previously named the companies they are investigating for links to Neves. Fonteles, who served as a prosecutor general between 2003 and 2005, said authorities should look into Domomedia now that its existence has been revealed.

"The facts that you discovered are totally connected with the other investigations,” he said.

Both the Office of the Prosecutor General and the Federal Revenue of Brazil declined to comment, citing the confidentiality of their investigations.

Neves did not respond to questions about whether he had declared the Luxembourg company to the Federal Revenue Service or the Central Bank.

Through a family lawyer, Fábio Tofic Simantob, he said his mother had been married for decades to a prominent Brazilian banker. “Her entire economic-financial and patrimonial life [is] linked to him and not to her children, as is widely documented,” he said.

Shortly after journalists reached out to Neves for comment on the existence of Domomedia, the company uploaded a new annual report to the Luxembourg Business Register with over 10 times more assets than its previous version. Asked about this sudden change, the Neves family lawyer said that a building Inês Maria Neves owned in Europe had recently been transferred to her Luxembourg company, after a delay due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inês Maria Neves has previously come under scrutiny by authorities. In fact, prosecutors are investigating another company she started in Liechtenstein, which they suspect may have been used to hide bribes solicited by her son.

Though Neves himself has been implicated in other corruption schemes, the scandals have not ruined his career. In 2018, after serving in several other political offices, he was elected to congress.

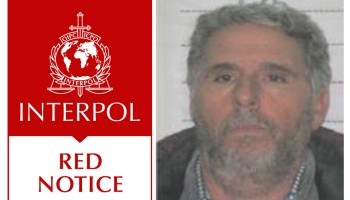

Luis Felipe Belmonte (left) and another supporter of Alliance for Brazil.

Firm Denial

Another powerful political player facing a financial probe is Luis Felipe Belmonte.

Belmonte is a vice-president of Alliance for Brazil, an organization backed by President Bolsonaro that aims to become the country’s dominant conservative party. He and other top members of the Alliance were under investigation for money laundering, but the details of the case were sealed, so its current status is unclear.

In 2018, Belmonte was elected as an alternate senator, meaning he would replace Senator Izalci Lucas if the latter was to leave office for any reason. Upon submitting his candidacy in the Federal District, which surrounds the capital of Brasilia, Belmonte was required to declare his assets to the Superior Electoral Court. Records show he declared 65.7 million Brazilian reals (about $17 million), including cash held in bank accounts abroad.

But Belmonte did not tell electoral authorities about Copalli Investments Sarl, a Luxembourg-registered financial holding company. Nor did he disclose its existence to Federal Revenue of Brazil, which is examining his assets because he owes about $1.8 million in taxes, according to information obtained through a Freedom of Information request.

In fact, Belmonte at first denied any connection to the firm, telling a reporter: "I do not declare to the Brazilian Federal Revenue anything in relation to Copalli, for the simple fact that I am not part of the membership, as a quotaholder or shareholder of that company, I have no ownership in relation to it.”

Belmonte backtracked when presented with evidence discovered by OCCRP in the Luxembourg registry, but added that he received no financial benefit from the company.

"There were plans to use this for future succession planning (with relation to heirs), but this was not done (I have 7 children),” he said in an email.

Copalli’s balance sheet for 2019 shows 17,044.92 euros in assets. Financial records for the company are unavailable, so it was impossible for reporters to determine what money had passed through the company’s accounts since it was founded in 2013.

Toxic Debts

In March 2017, residents of the impoverished municipality of Marituba were hit by a wave of illnesses that clogged hospitals, including skin and respiratory diseases. An insidious odor filled the air, forcing businesses to close, while the town water system and a nearby protected reserve became contaminated.

A toxic cocktail of chemicals was leaking from a landfill that held waste from nearby Belém, a northern city of more than 2.3 million people near the mouth of the Amazon River. The untreated waste could have filled 70 Olympic swimming pools, a judge later noted.

Landfill in Marituba.

At the center of this catastrophe was the Solví Group, one of South America’s largest waste treatment conglomerates. Solví executives were charged with a range of crimes, from negligence to fraud.

The state’s public ministry cited Solvi Group President Carlos Leal Villa as being personally responsible, arguing that his “malicious conduct” had harmed human health and the environment.

“Such accusations are unfounded, especially since Pará’s Public Ministry does not describe any act or conduct carried out by Mr. Carlos Villa that has impacted the environment or people's health,” Solví’s press office told OCCRP. “This leads to the necessary recognition of the complaint’s ineptitude, which is being discussed in the Brazilian courts.”

A judge ordered Brazilian banks to freeze around $26 million from the accounts of the four Solví companies, so it could be used for the clean-up. But making Solví pay further penalties for its crimes could be challenging, as much of its money is held in offshore accounts and companies.

OCCRP has discovered that Leal Villa created a network of firms in Luxembourg and multiple other jurisdictions used to shift Solví money and assets around. Each firm implicated in environmental crimes in Marituba is ultimately owned by a shell company in Luxembourg.

That could create a headache for Brazilian law enforcement.

One subsidiary was convicted of environmental crime last year and ordered to pay a further fine; the case is now under appeal. Marituba’s residents are still waiting for a final judgement on the other defendants, including Solví and Leal Villa himself.

"A judge would be able to block the assets in Brazil, but the rest depend on international cooperation,” said Davi Tangerino, a lawyer and professor of criminal law at Fundação Getulio Vargas university in Rio de Janeiro. “You have no guarantee that the country will comply with the judge.”

Solví’s published material makes no mention of any of its Luxembourg holding companies. Rather than each firm being tied to a particular aspect of the Solvi Group’s businesses, the companies are set up like Russian dolls, with one company owning another. While perfectly legal, this allows capital to flow through them and across borders.

Solví’s press office told OCCRP that the transnational structure was not a decision but rather the result of buying out the South American assets of the French utility firm Suez. It explained that in order to be able to purchase the Paris-based holdings, Leal Villa needed to set up a Luxembourg firm to do so, as he is not an EU citizen.

In fact, Leal Villa should have been able to take ownership in the French firm by simply making a declaration to France’s Ministry of Economy. Owning it via Luxembourg, however, offered tax benefits.

Solví told OCCRP that further companies were created to manage assets, admit partners and shareholders agreements, and it added that Solví has always declared its corporate chain of shareholders to the relevant authorities in accordance with applicable laws.

A view of Luxembourg.

Luxembourg Holdings

Information obtained through a Freedom of Information request to Brazil’s Central Bank shows that authorities know of only a fraction of the wealth held in Luxembourg.

Reporters with the Open Lux investigation found 448 companies owned by 228 Brazilian residents, and an additional 129 Brazilian citizens. Together, the assets of these companies amount to at least 113 billion euros, as of the end of 2020.

The Central Bank, however, was aware of only 176 Brazilian residents owning companies in Luxembourg as of 2019.

There are many legitimate reasons to start a company in Luxembourg, but Brazilian law requires it to be declared to authorities, according to Flávio Rubinstein, a tax law professor at Fundação Getulio Vargas university.

“When duly reported and compliant with Brazilian law, offshore entities can be legally used for estate structuring, international tax planning and asset protection,” he said.

Another reason people choose Luxembourg is the easy access it offers to international finance and corporate transactions. But the country’s financial secrecy also makes it an attractive option for Brazilians looking to hide or protect assets from government authorities or law enforcement.

“Brazilian courts can order the seizure of overseas assets and funds,” said Rubinstein, but he added that getting help from other countries can be a long and difficult process.

“The enforcement of such orders usually involves lengthy and costly procedures, such as activating international cooperation agreements, and requesting the assistance of foreign officials and courts,” he said.