As a wave of coronavirus infections hit Italy in late March, Rocco Molè, a member of the country’s ’Ndrangheta organized crime group, was faced with a dilemma.

He was holding on to 537 kilograms of cocaine, freshly smuggled into the southern Italian port of Gioia Tauro, which his clan controls. But due to lockdowns brought in to control the virus, he could only move small amounts of the drug at a time northwards to Europe’s cocaine users.

So he decided to bury the stash in a lemon grove.

The incident recounted in a statement by Italian police shows the predicament facing cocaine smugglers, as the global pandemic has increased scrutiny on them and disrupted their smuggling and distribution networks. But it also highlights their flexible approach to their trade, which has kept business booming even as many of the world’s legal sectors have ground to a halt.

In Molè’s case, the gambit turned out to be a costly mistake, according to the March 28 statement. Italian police, conducting lockdown checks, noticed him out and about and followed him to the grove where he had buried the plastic-wrapped bricks. He is now in jail facing drug trafficking charges.

But OCCRP reporters have found that the world’s cocaine industry — which produces close to 2,000 metric tons a year and makes tens of billions of dollars — has adapted better than many other legitimate businesses. The industry has benefited from huge stores of drugs warehoused before the pandemic and its wide variety of smuggling methods. Street prices around Europe have risen by up to 30 percent, but it is not clear how much of this is due to distribution problems, and how much to drug gangs taking advantage of homebound customers.

What is clear is that cocaine continues to flow from South America to Europe and North America. Closed trafficking routes have been replaced with new ones, and street deals have been substituted with door-to-door deliveries.

In Colombia, the world’s largest producer of cocaine, lockdowns and government eradication efforts have curbed some production, while travel restrictions have shut down some significant export routes, such as speedboats. In destination markets in Europe and the United States, authorities are still seizing large hauls with remarkable frequency — a sign that drug smugglers are still doing a brisk trade.

For over a month, OCCRP reporters in Europe and Latin America tracked announcements of seizures and spoke to law enforcement officials, analysts and sources within the cocaine trade.

They found an industry that has proved nimble at finding ways around the unprecedented global lockdown and quarantine measures. The cocaine trade is thriving in a world where even mainstays like oil are facing major disruptions.

As many countries begin partially reopening their economies, traffickers may now be in a position to become more powerful than ever. With economies in distress and many businesses facing ruin, cash-rich narcos may be able to cheaply buy their way into an even bigger share of the legitimate economy.

‘Stashes are Everywhere’

The pandemic initially affected production in the South American countries where coca leaves are grown and processed into cocaine. But that downturn in output never curtailed the trade, because most drug gangs have large amounts of stored drugs on hand.

In Peru, where roughly 20 percent of the world’s cocaine is produced, public health lockdowns imposed by local communities brought coca growing and paste production to a standstill, according to Pedro Yaranga, a Peruvian security analyst.

“What in nearly four years the drug control agency could not do, the coronavirus did in a few weeks,” he said.

In Bolivia, which produces about one tenth of the world’s coca, the picture is reversed, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). In that country, “COVID-19 is limiting the ability of state authorities to control coca bush cultivation, which could lead to an increase in coca production,” the UNODC said in a May 7 report.

In Colombia, where 70 percent of the world’s cocaine is produced, the picture is more mixed. Anti-narcotics police eradicated over 1,969 hectares of coca plantations in the three weeks after lockdowns came into nationwide effect on March 25, the country’s anti-narcotics police told OCCRP.

“The perception of the population is that [the government] is taking advantage of the quarantine and people being stuck in their homes to eradicate” coca, said Jorge Elías Ricardo Rada, the head of a union that represents small farmers’ interests in the region of Cordoba. “They take away what little the people have.”

In Catatumbo, a region near the Venezuelan border, “the business is practically paralyzed,” said Giovanny Mejía Cantor, an independent journalist based in Ocaña, the region’s main city. Normally, the area produces enough coca in a year to make 84 tons of pure cocaine, but this has slowed to a trickle.

“Communities have gone onto the road and set up blockades to prevent people from entering their village out of fear of coronavirus,” said Mejía, adding that this has hindered the movement of raw materials needed in production, including coca leaves and chemicals.

The country’s biggest exporting cartel, however, does not appear to have suffered. Members of Colombia’s Gulf Clan said they had been able to fall back on stockpiles built up before the pandemic, as well as coca leaves from smaller farms that are still functioning and don’t require a big workforce.

The Gulf Clan stronghold lies in Urabá, in Colombia’s northwest, a strategic region with coca plantations, laboratories, and export ports. The group typically has roughly 40 to 45 tons of processed cocaine stored in that area, roughly two months’ worth of exports, according to a Gulf Clan member, who asked to be identified as “Raúl.” He declined to be named because doing so would put him in legal and physical danger.

“There has always been a stock, it’s a very organized chain. It’s the way to control everything, especially the price. The stocks are on beaches such as Tarena [near the border with Panama], banana plantations, in the jungle. The stashes are everywhere,” said Raúl.

A Colombian navy intelligence report from April obtained by OCCRP also concluded that cartels were likely exporting cocaine that had been warehoused before the COVID-19 crisis.

The Colombian navy also found that cocaine producers have easily adapted to challenges in moving their product. The United States, up north, is their largest single customer.

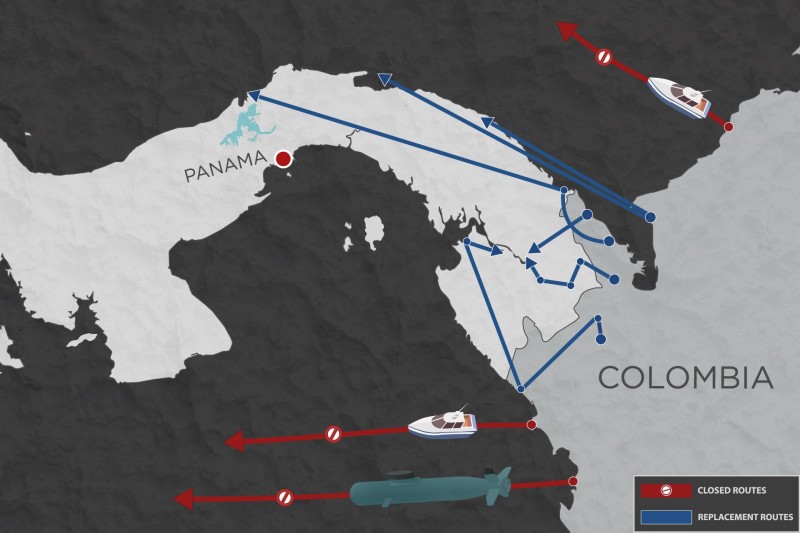

Traditionally, smugglers have used small, very fast speedboats, as well as fishing vessels and submarines, to ply their northern route. Lockdowns have made these methods harder to use, mainly for logistical reasons. So instead, smugglers are turning back to older, slower routes that are often broken up in parts.

Based on several sources in northern Colombia, including Raúl and a coca grower, OCCRP was able to roughly trace six new or revived routes believed to be currently used by traffickers. These include routes into Panama through indigenous areas.

Members of the Kuna indigenous people are bringing drugs overland, making small boat runs up coastal waters. In the Darien Gap, a thick, mountainous jungle on the frontier of Colombia and Panama, cocaine is being hauled by caravans of up to two dozen backpack-toting porters.

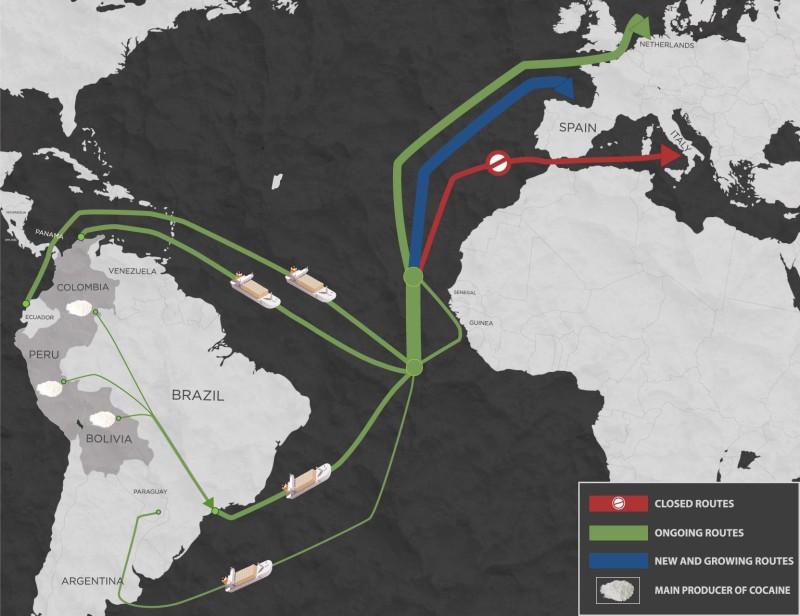

Exports to the world’s other biggest cocaine market, Europe, have suffered even less disruption. Unlike exports to the United States, cocaine bound for Europe is typically moved in legal air and sea cargoes, especially fast-moving fresh goods such as flowers and fruit. The latter, as food, has continued to move unimpeded during the pandemic, helping feed Europe’s 9.1 billion euro-a-year cocaine habit.

Colombia’s banana industry, for example, has been exempt from local lockdown measures, allowing cocaine to keep moving through the crop’s supply chain.

“[Anyone] in the authorities or security that meddles with this route goes down,” said Rául, the Gulf Clan member, adding that people who are paid off to facilitate the smuggling of cocaine have an incentive to keep the drugs flowing.

“Everybody eats,” he said.

South America’s third main export route — in which Colombia, Peruvian, and Bolivian cocaine is brought overland and then sent across the Atlantic from the Brazilian port of Santos — is still running, said Lincoln Gakyia, a São Paulo state prosecutor in charge of fighting organized crime.

The main Santos trafficking group, Primer Comando da Capital, has managed to maintain some of its supplies, but it is unclear how long its stockpile will hold out, Gakyia said.

In Mexico, the cartels that control trafficking northwards into the United States have flourished under lockdown conditions. Seizures across the US border rose over 12 percent in the two weeks after the travel restrictions were imposed, indicating ongoing heavy traffic, according to figures from U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

Drug smugglers “have moved away from the traditional method of sending frequent but small shipments across the southwest border to less frequent but larger shipments,” the DEA said in response to reporters’ questions, adding that it was unclear if this was the result of COVID-19 or other factors.

Mexican cartels have used the crisis as a public relations opportunity. People associated with the cartels, including the daughter of imprisoned Sinaloa cartel chief Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, have publicly distributed food and other essential items to the poor.

Meanwhile, the country’s drug violence continues unabated, claiming an average of 80 lives per day.

“They may be giving groceries to Chapo’s mother’s friends, but that doesn’t mean they care about the good of the country,” said Guillermo Valdés, the former head of Mexico’s national intelligence agency.

Record-Breaking Seizures

In Europe, the pandemic has led to a surge in large seizures at ports, and has accelerated a trend that is making Spain an increasingly important entry point for the continent’s cocaine supply. Despite the large number of seizures, drug dealers throughout Europe are not seeing major disruptions to their cocaine supply.

In March and April, Spain seized over 14 tons of cocaine in inbound shipments — a figure six times higher than the same period the previous year, said Manuel Montesinos, the deputy director of Customs surveillance at the Spanish Taxation Agency.

“We are very struck by the frenetic pace,” Montesinos said. “Almost every day we receive alerts of detections of suspicious operations.”

In one instance, Spanish authorities seized four tons of cocaine from a ship about 555 km off the coast. The Togo-flagged ship was an offshore supply vessel, not designed for a voyage on the open seas. Yet, the ship had last been anchored in Panama and sailed across the Atlantic, towards Spain’s Galician coast, with 15 people on board.

At least seven other major shipments of over 100 kilograms have been seized in Spain, mostly in incoming freight. Four of them weighed over a ton.

Ramón Santolaria, the head of anti-narcotics at Spain’s national police in Catalonia, said cocaine traffickers may have mistakenly assumed that the pandemic would have reduced monitoring at ports.

The cartels “have to continue exporting,” Santolaria said. “They are like a company. They can’t store everything in their countries, since it would be very risky.”

While Spain’s ports have seen a cocaine boom, Italy has fallen silent as a point of arrival, despite being home to mafia groups that dominate Europe’s cocaine trade.

Seizures dropped by 80 percent over the months of March and April compared to the same period last year, according to Riccardo Sciuto, director of the Direzione Centrale dei Servizi Antidroga (DCSA), Italy’s anti-drug agency.

Cocaine destined for the local market is now arriving via road from the rest of Europe. .“Italy did not receive much via ports or airports and that is because during lockdown we have been controlling them a lot,” said Marco Sorrentino, the head of anti-mafia department of Italy’s financial police, the Guardia di Finanza.

Italian crime groups have shifted their operations to Spain, where they have large “colonies” according to Sorrentino.

“Italian mafias and their partners thus sent cocaine mainly to Algeciras or Barcelona, and then from there they moved it on wheels to the rest of Europe and to Italy,” he said. “As cover-up they used trucks filled with fresh fruits or also soy flour,” which resembles cocaine.

In the large northern European ports of Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, and Antwerp, in Belgium, cocaine continues to arrive as before, hidden in shipments of legal consumer goods, according to local authorities.

"Let's not be under any illusions, criminals will go on ruthlessly," said Fred Westerbeke, Rotterdam’s chief of police.

“We see even more activity in the port. In recent weeks we have picked up a lot of collectors [of drug shipments]. These are people who empty containers of drugs before we find them,” he said, adding that there have been over 40 such arrests since lockdowns came into effect.

Perhaps as a response to increased seizures, the street price of cocaine has risen by 20 to 30 percent during the lockdown period from mid-February until the end of April compared to the same period last year, according to Sciuto of the DCSA. Six months, criminal groups in Europe paid 25,000 to 27,000 euros for a kilogram of cocaine; they now fork out 35,000 to 37,000 euros, he said, adding that Spanish police have noticed the same trend.

Deliveries and the Dark Web

At the street level, lockdowns have played havoc with cocaine sales — but have also failed to stop the trade. But in some cases at least, dealers’ adaptations may have actually put them in a more profitable position than before, as cocaine users are desperate and confined at home.

“Even though they don’t lack product, they have raised prices a bit and are cutting it more,” said Sorrentino of Italy’s Guardia di Finanza, referring to the process of diluting cocaine with cheaper substances.

Cocaine dealers and regular users in Rome said it took several weeks for new distribution methods to come into effect after strict lockdown measures made regular dealing too risky.

The solution? Delivering it to customers in the guise of food orders, or couriered by essential workers carrying documents that give them permission to move around freely. Dealers have also staked out positions in socially distanced queues outside supermarkets — one of the only permitted places to gather in public under Italy’s strict lockdown rules, which began easing up in early May.

Lockdown restrictions have also led to a rise in trade over the dark web, part of the internet that isn’t visible to search engines and must be accessed using special software that conceals the identities of users.

“We have seen an increase of dark web being used also in Italy, and there is the rule of the ‘coronasale’ - discounts for the COVID-19 pandemic,” explained Sorrentino, adding that the large quantities on offer indicated that the discounts were aimed at dealers rather than individual users.

Advertisements for “Colombian cocaine” have increased along with the number of sellers in both markets, where dealers offer a gram of 80 percent pure cocaine for $80. The street price for a gram is about the same, but the purity tends to be much lower.

Many customers seemed satisfied: “Excellent service in hard times,” one wrote.

The main dark web marketplaces have seen an increase in sales of roughly 30 percent since lockdown measures started coming into effect worldwide, but it's not possible to identify the origin of the sellers, according to Giovanni Reccia, head of the Special Unity for Online Crimes Prevention of Italy’s Guardia di Finanza. Most of them declare that they are based in the Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom.

Just as before the crisis, cocaine made up roughly 15 percent of all dark web drug sales, trailing behind marijuana, which has a quarter of the online illegal drug market.

The result of the ongoing cocaine trade, according to Guardia Finanza’s Sorrentino, is that organized crime groups are likely to emerge from the crisis with plenty of money in an economy where many others are struggling.

“Private citizens who are in need and won’t have access to a bank loan will be victims of loan sharks,” he said. “But what worries us the most is that licit companies might be in need, and be approached by mafia organizations that will propose to become minority shareholders.”

“And once this happens, they actually take over the whole company,” warned Sorrentino.

Additional reporting by Koen Voskuil, Raffaele Angius, Bibiana Ramirez, Juan Diego Restrepo E., and Luis Adorno.

This story was done in collaboration with Algemeen Dagblad newspaper in the Netherlands and VerdadAbierta.com in Colombia.