For years, Argentinian prosecutors and observers have been puzzled by the behavior of Meinl Bank, an Austrian financial institution that swooped in to buy up millions of dollars of debt accrued by Argentina’s postal service after it was privatized and sold to a powerful political family, the Macris.

Meinl has repeatedly made decisions that seemed to favor the Macris, while hurting the interests of the Macris’ creditors — including Meinl itself.

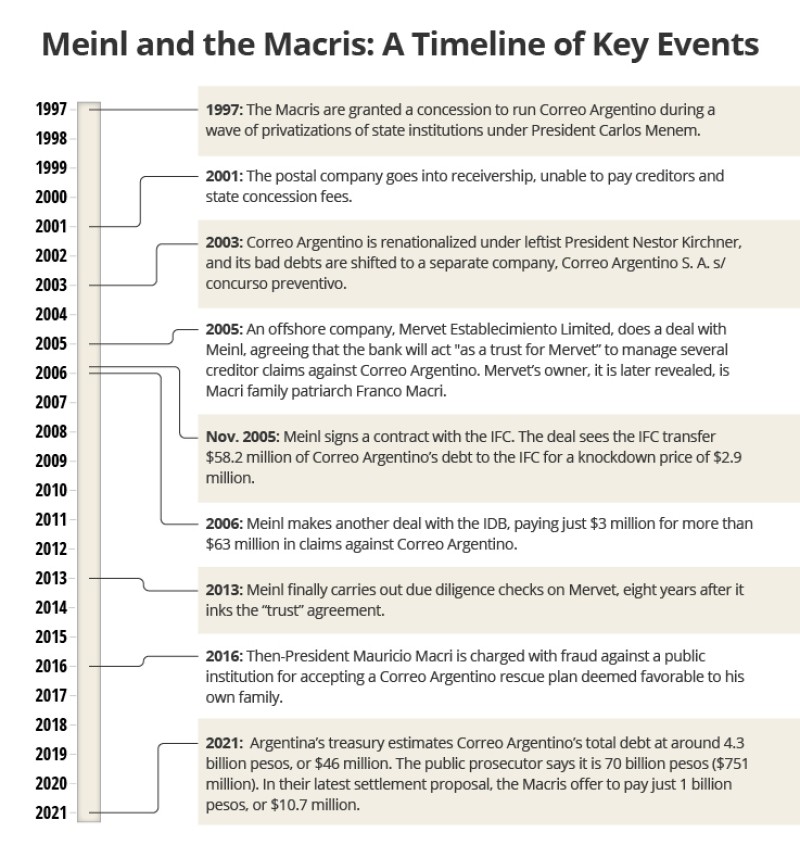

Now, an investigation by OCCRP and La Nación can reveal that in 2005, just months before Meinl bought up nearly 40 percent of Correo Argentino’s debts, the bank signed a secret agreement with an offshore company linked to the Macri family patriarch, Franco Macri.

In the agreement, Meinl Bank said it would manage the claims of several Correo Argentino creditors on behalf of this company, based in the secretive European principality of Liechtenstein, according to a leaked audit report obtained by Austrian media outlet Profil and shared with OCCRP.

Although this is a major new piece of information in a nearly 20-year-old legal battle over Correo Argentino’s debts, showing that Meinl had a prior commercial relationship with Franco Macri, it also raises many questions.

For one thing, it’s unclear what exactly this trust did, or how Macri could have been in a position to give Meinl these debts.

According to an anti-money-laundering investigator who reviewed the audit for OCCRP, the agreement would only make sense if either Franco Macri or the Liechtenstein company, Mervet Establecimiento Limited, already owned at least some part of Correo Argentino’s debt. But there has never been any public indication that they did.

The investigator, who works for a tax agency in a European country and asked to remain anonymous because he is not allowed to speak to the media, said the agreement was unusual and hard to understand.

It's also unclear what, if anything, in the agreement led Meinl to quickly begin acquiring the claims of Correo Argentino’s main private creditors through the trust. By the time its buying spree was over, it owned 38 percent of the company’s total debt, giving it significant leverage over other creditors — which it used to the Macri family’s advantage.

The bank also committed serious breaches of compliance, which may have been done in an effort to “disguise assets,” according to the audit, which was carried out in 2015 by accountancy giant PwC on behalf of the Austrian government.

Most strikingly, Meinl didn’t perform the required due diligence checks on Mervet until 2013, eight years after the agreement was signed. A so-called “Know Your Client” document was only created that year too, and no risk assessment of Mervet was ever conducted.

Taken together, these facts should have been grounds to report the agreement to authorities, the auditors wrote. The compliance expert who reviewed the audit said these lapses were so significant they suggested that Meinl Bank had colluded with Macri to conceal his identity.

The expert suggested the unusual setup — in which Meinl became both a creditor and a partner of Franco Macri — may have been intended to give “a privileged VIP client ... preferential treatment.”

It’s unclear what will happen to Meinl’s portion of Correo Argentina’s debt since the bank collapsed in disgrace last year, after facilitating an asset-stripping operation that siphoned fortunes from Eastern European banks. Peter Weinzierl, deputy chairman of the bank's parent company, said he had no information about the trust agreement mentioned in the audit.

Franco Macri died in 2019, and a spokesperson for the Macris said the family had no knowledge of his Liechtenstein company.

“Correo Argentino never assigned anything to any Trust, nor is it part of or aware of the existence of any agreement between Mervet Establecimiento and Meinl Bank,” the family said in a statement to OCCRP.

Correo Argentino: The Scandal Haunting the Macris

Both Sides of the Table

Eight weeks after Mervet signed the secret trust agreement with Meinl, the bank started buying up Correo Argentino's debts for cents on the dollar, according to Argentine court documents obtained by La Nación and OCCRP.

When Correo Argentino declared itself insolvent in 2001, it was in debt to multiple private creditors, chief among them the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), to which it owed hundreds of millions of dollars.

On November 7, 2005, Meinl Bank signed a "contract of assignment and assumption of responsibilities" with the IFC. According to court documents examined by La Nación, the IFC transferred the $58.2 million in loans it had with Correo Argentino to Meinl for just $2.9 million.

Less than eight months later, Meinl made a similar deal with the IDB, paying $3 million for its more than $63 million in claims against Correo Argentino. (The IDB did not respond to several requests for comment, while the IFC said the deal took place so long ago that it was impossible to direct questions from OCCRP to the relevant people.)

Thus, in under a year, Meinl Bank became Correo Argentino’s main private creditor, controlling debts of $121.3 million — for which it had paid less than $6 million. Court documents show that this accounted for 38 percent of Correo’s debt to private creditors, but 71 percent of the votes that determine how the debt is dealt with.

Once these deals had been secured, Franco Macri’s secret banking partner was in a position to play a lead negotiating role on the issue of Correo Argentino’s debt, and even force an agreement with all the company’s private creditors on how much the family would have to pay.

A ‘Fictitious Majority’

According to Argentine law, if creditors controlling two-thirds of a company’s debt agree on a payment plan, they can impose it on other creditors. If approved by a judge, this decision becomes binding.

It started to make decisions that appeared to favor the Macris.

In September 2007, Meinl agreed to extend the terms of the insolvency process, even though the move would theoretically affect its own claims to outstanding debts. A later court opinion pointed out that the extension only helped Correo Argentino, since "the passage of time has the main consequence of dissolving the credit to the detriment of the creditors."

In July 2007, Meinl accepted a Macri proposal that 50 percent of Correo Argentino’s debt be written off. Under the terms of the plan, the next 30 percent would be paid in 15 annual installments, with an interest rate of a below-inflation 5 percent, and an initial grace period of five years. The remaining 20 percent would be paid via funds the Macris expected to receive from the Argentine state if they won lawsuits related to the Correo Argentino dispute.

Thanks largely to the weight of Meinl’s votes, Correo Argentino's private creditors accepted the deal.

Gabriela Boquín, the lead prosecutor on the case, publicly questioned the decision, saying it did not make sense.

"If the ridiculous nature of the proposal is taken into account, it can only be affirmed that the third party that replaced the creditor [Meinl Bank] has voted contrary to its interest as a creditor,” she wrote in 2016 in an opinion submitted as part of the bankruptcy proceedings.

Despite the creditors’ acquiescence, the Argentinian state — which as the owner of Correo Argentino had veto power over the agreement — rejected it.

Correo Argentino accused the state of being a "hostile creditor,” pointing out that private creditors had agreed to the deal, and asked for it to be excluded from negotiations. (Judges rejected this request.)

Six years later, as the case made its way through the courts, Meinl approved a proposal from the Macri family to convert its debt into Argentine pesos. Once more, the deal appears to have favored the Macris, since Argentina’s currency has been plunging in value.

When Correo Argentino went bust in 2001, the Argentine peso was pegged to the U.S. dollar. After a series of devaluations in the subsequent years, the deal to convert the debt to pesos was agreed upon in December 2013, when the exchange rate was 6.525 pesos per dollar. Today, there are around 93 pesos to the dollar.

What’s in a Debt?

Prosecutors said Meinl’s votes also had "a determining weight” in a controversial plan put forward in 2016 that would have spread repayments over 15 years at a below-interest inflation rate. According to prosecutors, this would have effectively forgiven 99 percent of the postal company’s $296 million debt to the state. The deal was quietly approved by Correo Argentino’s creditors and by the government of then-President Mauricio Macri, but was stopped by the courts.

In February 2017, Macri was charged with public administration fraud over what prosecutors said was a blatant conflict of interest in accepting the deal. He has never been formally summoned over the charges, and the current status of the case against him is unclear.

While the Macris were negotiating with their creditors, the audit shows, the ties between them and Meinl Bank were multiplying.

The audit revealed that Mervet Establecimiento Limited, Franco Macri’s Liechtenstein offshore company, signed yet another agreement with the bank in 2006, this time regarding the bank’s claims against Socma, one of the Macri family’s main companies. Then in 2008, Socma and Meinl signed two more deals, including a debt restructuring agreement, although it’s not made clear in the audit what this entailed.

Again, the auditors pointed out, Meinl’s poor due diligence checks may have violated Austrian banking law. They said that the transactions raised “a suspicion of money laundering” and therefore should have been reported to authorities.

The Macri family said through a spokesperson that Socma “does not have any relationship” with Meinl.

“Socma never assigned any claims or claims management or anything else to Meinl Bank,” the family spokesperson said. “Socma restructured all of its debts directly and on its own, and did so with all of its creditors.”

It remains unclear why Meinl entered into these deals with the Macris’ companies, and why some of them appeared to go against the bank’s own interests. But the sheer length of the dispute has played into the Macri family’s hands, according to prosecutors.

"Correo Argentino benefited from a state of 'eternal' insolvency and managed to suspend payment to its creditors for more than fifteen years," Boquín, the commercial prosecutor, wrote in her 2016 legal opinion.

Countdown to a Decision

Almost two decades have now passed since Correo Argentino collapsed and its bad debts were hived off into a separate company. Ever since, this debt-laden vehicle, Correo Argentino S. A. s/ concurso preventivo, has been in limbo, with the Macris, the creditors led by Meinl, and the government unable to agree on a payment plan.

But now, the seemingly endless battle over who should foot the bill may finally be over.

In the coming days, Judge Marta Cirulli of Buenos Aires will rule on whether to accept a proposed settlement put forward by the Macris, who have offered to pay 1 billion pesos (around $10.7 million) to discharge all Correo Argentino’s debt.

Argentina’s treasury says this is far too little for a company that owes the equivalent of at least $46 million. Prosecutors want a declaration of bankruptcy, which would allow the court to seize all of Correo’s assets and distribute them among its creditors.

If that happens, in a worst-case scenario for the Macris, family members who own shares in Socma — including Mauricio, his brother Gianfranco, and several of their children — say they might have to pay off Correo Argentino’s debts with their own money.

So it’s no wonder that the family are pushing for their settlement proposal to be accepted. They argue that the majority of their creditors approved it — including Meinl, before it went bankrupt.

“It is an unbeatable proposal,” they said.

Kornelija Ukolovaite (OCCRP) contributed reporting.