Reported by

From his apartment overlooking the picturesque Narta lagoon in Albania’s south, 72-year-old Jorgaq Subashi can glimpse the land he was awarded in 1993 as part of the government’s attempt to return property seized under communist rule.

But he is not allowed to live on it.

Almost three decades after winning the land back, Subashi and 34 fellow villagers have yet to receive their property deeds. They remain embroiled in seemingly interminable bureaucracy, despite a court confirming in 2012 that their properties had been unlawfully transferred to a powerful local clan linked to the theft of swathes of the country’s southern coastline around the city of Vlora.

“We know that the lands were taken from us by the collectivization of agriculture during the communist regime,” said Subashi. “After the ’90s, the state gave them back to us, but we still cannot register them.”

The villagers’ plight is common in the Balkan nation, one of the poorest countries in Europe, where attempts at land reform have been hampered by mismanagement and corruption. In some cases, the process has been hijacked by alleged gangsters like Artur Shehu, who, along with some of his family members, is accused of stealing nearly 500 hectares of prime real estate near Vlora.

An underworld figure accused of having ties to organized crime in Albania, and a powerful branch of the Italian mafia, Shehu fled his homeland in 1999 after a deadly gunfight in his bar in Vlora.

He sought asylum in the U.S., and received it in 2001. In 2019 he got a green card, paving the way for him to become a citizen. Despite his hasty exit from Albania, he has continued to direct operations there from the safety of a mansion on the Florida coast.

Shehu has not officially been accused of a crime, but his associate Pellumb Petritaj, who oversees many of his properties, has been found guilty of using forgery to obtain land on behalf of the Shehu family.

Shehu’s activities are, however, well known locally. A judicial commission described him in 2018 as “a key player” in land theft around Vlora. When asked why no action had been taken against Shehu despite evidence from multiple cases and jurisdictions, the prosecutors’ office in Vlora declined to comment.

Shehu refused to reply to questions about the matter. He instead approached OCCRP through an intermediary, who offered a reporter “whatever you want” in exchange for dropping the story.

But after years of maintaining a low profile in his home country and working through intermediaries, Shehu’s name has recently appeared on documents showing new business interests in the Albanian Riviera, a long stretch of turquoise-edged coastline along the Adriatic Sea.

In 2019 he co-founded a hotel development firm called Portonova, which shares a name with a beach on the outskirts of Vlora. In April last year, he opened another firm to develop tourism sites, Adhenis. It appears that Shehu is presenting a new public image — one that is a far cry from his alleged criminal background in a city once teeming with gangsters.

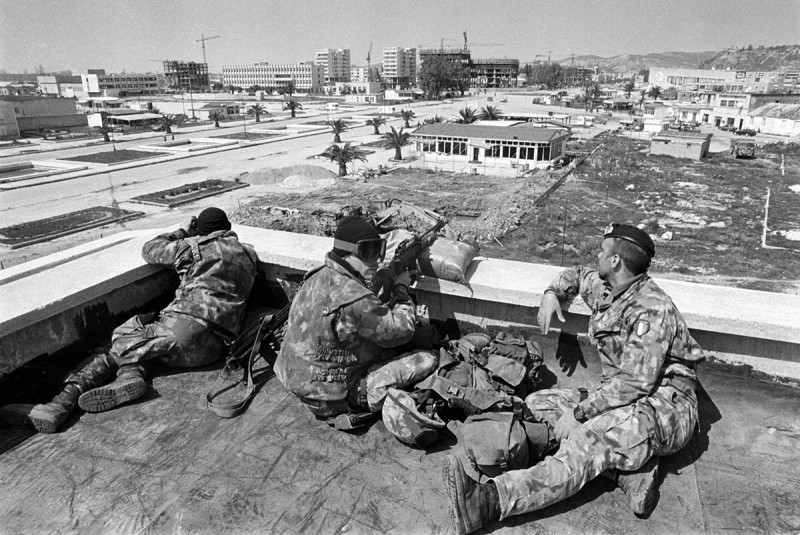

City of Gangs

Life in Vlora in the late 1990s was pure mayhem. Hadër Cako, who headed an investigative unit in the local police force during that period, recalls that for several years, the city was entirely in the grip of local gangs.

The Albanian economy collapsed after several nationwide pyramid schemes fell apart in 1996 and 1997, and the country descended into civil conflict, prompting a United Nations military intervention led by Italy.

“The police station was without windows or doors, without cells,” Cako told OCCRP. “The city was totally in the control of the local criminal gangs. The city was a ring of brutal killings, rape, theft.”

Shehu, fresh from a stint in Albania’s special forces, was well known among police in Vlora at the time for criminal activity, according to a former Vlora police chief who asked not to be named for safety reasons.

“He had a hotel, and later on he built a casino,” said the former official.

Dritan Zagani, who headed the anti-narcotics unit in the city in the late 1990s, said he had cooperated with an Italian anti-drug unit probing a crime ring that Shehu was allegedly involved with.

“There was an open investigation into an Italian-Albanian organized crime group for the offenses of trafficking in human beings and narcotics,” said Zagani.

Cataldo Motta, a former prosecutor in the southern Italian city of Lecce, which lies just 112 km west across the Adriatic Sea from Vlora, also remembered the case involving Shehu: "It is a well-known name. He was in our files suspected of drug trafficking."

Shehu provided OCCRP with a letter dated June 2016 from the prosecutor’s office in Lecce saying he had not been convicted in that jurisdiction, but refused to answer questions on the matter, or to comment for this story.

Shehu’s time in Vlora ended after the 1999 gunfight in his bar, according to Zagani. He said gang members killed two people in the attack, including Shehu’s uncle, Luan Bedini.

“Luan died in Artur's arms and he vowed to avenge the murder of his uncle,” said Zagani.

He said police wanted to question Shehu about the shooting and his alleged involvement with a local crime syndicate, but he fled the country.

According to U.S. court documents, Shehu has been a resident of that country since at least 2001, when he was granted asylum. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, which processes asylum claims, said it was unable to disclose any information on the case.

In 2005, he moved to Miami, where he built a colonial-style villa overlooking a golf course, complete with columns and an ornate crest. The property has been valued at up to $3 million. Florida property records show that, in addition to the four-bedroom villa, Shehu previously owned a series of condos in and around Miami.

Shehu’s house sits in an upscale neighborhood just minutes away from the Miami Beach oceanfront, with a manicured lawn flanked by trees. Two Mercedes-Benz cars were parked in the driveway when a reporter from the Miami Herald visited the property.

In addition to placing a letter with questions in Shehu’s mailbox, the Herald also sent questions via Fedex, which someone at the address signed for. Shortly afterwards, Shehu contacted a reporter in Albania through an intermediary, who offered “whatever you want” in exchange for dropping the story.

Mafia Connections

Although Shehu has spent nearly two decades living in Miami as a refugee, Italian anti-mafia investigators believe that he has continued to conduct business in Albania –– sometimes allegedly on behalf of Italian gangsters.

Guglielmo Cataldi, another prosecutor in Lecce, said Shehu was investigated in 2012 for his role in allegedly investing money in Albania for Albino Prudentino, a senior member of the Italian mafia organization Sacra Corona Unita.

An Italian court document obtained by OCCRP shows that, from 2009, Prudentino rented part of a luxury building owned by Shehu in Vlora’s Uji Ftohtë neighborhood. The Italian mob boss ran a restaurant and gelateria on the ground floor and a casino upstairs.

Prudentino was found guilty in 2013 of laundering mafia money through these businesses, and sentenced to three years in prison. Italian prosecutors alleged that Shehu made 1 million euros helping him do it, although they noted that they did not have enough proof to charge him.

Shehu was not charged in Italy, but Cataldi said the case against him was passed on to Albanian investigators. “We sent the data we had to Albania, showing them what the investments were, but I don't know how this investigation went.”

Albania’s state prosecution, police, and the Vlora prosecution office all declined to comment on the case.

Beginning in 2006, from his opulent perch in Miami, Shehu started amassing a vast portfolio of properties around Vlora — through means that local residents say were illegal.

Although he and his family benefited from the alleged fraud, Shehu has never been directly charged over the land cases. However, a close associate of his, Pëllumb Petritaj, was convicted in 2018 of forging land documents to usurp 187 hectares of land.

In other court cases involving a total of nearly 300 additional hectares near Vlora, Shehu and his family members are accused of grabbing property through similar forgeries. This includes the land on the shores of the Narta Lagoon that Subashi and his fellow villagers say were stolen from them.

In these ongoing cases, Petritaj would allegedly forge documents with the help of local officials to get land into the hands of Artur and his father, Ramis. Sometimes a third party would receive the land, then transfer it to the Shehus.

Despite the lack of legal action against Shehu, at least some in the judiciary are aware of his reputation for expropriating land around Vlora.

A disciplinary case in 2018 saw Artur Malaj, a judge in Tirana who had previously served as the head of the Court of Vlora, sacked for a host of ethical failures, including an allegation related to Shehu. Among the findings of the investigation into the judge was that at least one of his family members had bought land from Shehu, which Malaj failed to report.

“A. Sh is suspected of being a key player in the process of property alienation in Vlora,” the report reads, referring to Shehu.

The judge told OCCRP that just one family member had bought land from Shehu. He said he had no knowledge of this until the investigation uncovered it, and insisted that he has had no contact with Shehu.

“I have been a judge in the city of Vlora for around 10 years. In not a single case have I had any property issues or other issues which were related … to Artur Shehu or his family," Malaj said.

Even those with substantial resources at their disposal have been forced to cut deals with Shehu. They include a charitable foundation formed in 2014 with the mission of reclaiming the ancestral estate of the Eftimiadis, a well-to-do family that emigrated from Vlora to Italy in the early 20th century.

The Eftimiadi family estate was caught up in the political and ideological shifts that shook Albania throughout the 20th century. By the early 2000s, a century after the family emigrated to Italy, attempts to reclaim the property were ensnared in corruption and judicial inefficiency.

After discovering that part of the estate had been taken over by Shehu, the foundation’s board — which included a former Italian diplomat and a retired general in Italy’s financial police — opted to cut a deal with him.

The Luca and Marco Eftimiadi Foundation signed a contract with Shehu in 2015, agreeing to accept eight apartments and three hectares of coastline. None of those properties were originally part of the estate, and the foundation agreed to give up any claim to the ancestral land. Petritaj signed the contract on behalf of Shehu.

The deal quickly fell apart.

The foundation had intended to build a small marina that would generate funds for its charitable mission, which included building bridges between Albania and Italy. That plan ground to a halt when the foundation realized the land transfer was based on forged documents, according to Namik Alimuçi, an Albanian businessman who has run a beach bar on the property for 15 years.

“They are all fake and the whole village knows this,” said Alimuçi, who was supposed to work with the foundation on the seafront development.

Competing Claims

The saga of the Eftimiadi family estate is one of thousands of similar stories throughout Albania, which is caught in a web of competing land claims — a legacy of the communists who nationalized property, and a subsequent spree of theft during attempts to return it to private ownership.

Land issues around Vlora are particularly complicated, according to Elona Hodaj, a former director of the Real Estate Registration Office in the city.

"It is a situation created over 25 years,” she said. “There are court decisions that have given the same property once to one party, and once to another party.”

Hodaj lasted less than a month on the job. She is one of eight directors to have resigned since September 2019, each citing “personal reasons” for leaving.

When he swept to power in 2013, Prime Minister Rama pledged to resolve Albania’s land crisis and make sure stolen properties were returned to their rightful owners.

“Albania cannot be the country that the next generation will inherit as a place where robbers and counterfeiters enjoy once and for all the product of their criminal acts,” Rama said in 2015.

His government’s efforts have so far seen little success. Alleged land thieves like Shehu have prospered, while others like the Eftimiadi Foundation and the villagers in Zvërnec, near the Narta lagoon, have been unable to regain their properties.

After failing to negotiate a bureaucratic and legal maze of land claims, Subashi and his fellow villagers are left with an unlikely last resort. “We have been writing to every prime minister for years,” said Subashi. “We have also written to Edi Rama.”

Shirsho Dasgupta (Miami Herald), Megan Bobrowsky (Miami Herald), and Valerio Cataldi (TG3) contributed reporting.