But in the East, things went the other way, with officials calling the investigation “fake news” and announcing stricter online censorship.

In cooperation with the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, OCCRP and media partners from 39 other countries investigated how Credit Suisse exploited Swiss banking laws in order to provide criminals and the corrupt a safe haven for their ill-gotten gains - something the bank has denied.

“Bank privacy laws must not become a pretext to facilitate money laundering and tax evasion,” said Markus Ferber, Member of the European Parliament and Spokesman for the European People’s Party, EPP, in the Economic and Monetary Affairs Committee.

“The “Swiss Secrets” findings point to massive shortcomings of Swiss Banks when it comes to the prevention of money laundering. Apparently, Credit Suisse has a policy of looking the other way instead of asking difficult questions,” he said.

This turns Switzerland into a high-risk jurisdiction, he said and suggested that “when the list of high-risk third countries in the area of money laundering is up for revision the next time, the European Commission needs to consider adding Switzerland to that list.”

Joseph Stiglitz, an American economist and former World Bank senior vice president, said that the leaked accounts represent only “a small portion of the banks’ client data.”

“If in this tiny portion are already so many problematic customers, dictators and their families, war criminals, intelligence officials and chiefs, corrupt managers, human traffickers, heads of state, sanctioned businessmen and human rights abusers—a true rogue’s gallery—what would we see if the window into the bank were larger?”

“Banks cannot be trusted to police themselves,” said Maíra Martini, an anti-money laundering expert at Transparency International. “The public is tired of hearing about how banks help corrupt officials from around the world launder their money – and how they will do better next time,” she added.

A “slap on the wrist” is insufficient to deter such repeated behaviour from the banks. And “as a global community, we need to clamp down on banks that serve corrupt interests, keeping their outsized influence on political decision-making in check,” Martini concluded.

Switzerland’s Green Party said that parliament is not doing enough to prevent financial and tax crime. “Switzerland must no longer be the place where autocrats, dictators and criminals from poorer countries hide their money,” the party said in an official statement.

Switzerland is renowned for its protection of banking secrecy. Article 47 of the country’s 1934 Banking Act states that anyone who “discloses information about bank customers to other people” can be punished with up to three years in prison. This applies even to journalists who expose criminal behaviour or other wrongdoing of urgent public interest.

This is why no Swiss reporters could participate in the Suisse Secrets investigation.

“Switzerland simply does not respect European legal standards on freedom of expression and freedom of the press,” said the General Secretary of the European Federation of Journalists, Ricardo Gutiérrez.

“It favours the particular interest of bankers over the general interest. The necessary public debate is confiscated,” he said, adding that the case law of the European Court of Human Rights is not applied in Switzerland. “This practice is worthy of the worst authoritarian states. It must be stopped.”

The Green Party called for revisions to the country’s Banking Act that will protect “media professionals and whistleblowers from criminal prosecution” as a result of their investigations into the country’s banking practices.

The response from countries of the Middle East and Central Asia, however, has been completely opposite.

Jordan’s Royal Hashemite Court said that the recently published media reports on bank accounts for His Majesty King Abdullah II, “included inaccuracies, and outdated and misleading information that were employed with the aim of defaming Jordan and His Majesty, as well as distorting the truth.”

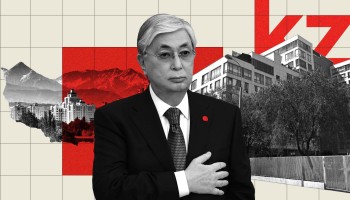

Kazakhstan decried reports of President Tokayev’s offshore secrets as fake news. Berik Uali, the President’s press secretary, wrote on Facebook that neither the President nor his former wife had any accounts in Swiss banks.

He added that “this is a fake information attack on the President that has a goal to discredit him,” because he is trying to block a monopoly in the economy.

Reportedly, hundreds of bot accounts have sprung up on Telegram to denounce the investigation as fake news. In response, journalist and activist Assem Zhapisheva commented on Twitter that “Tokayev has a better bot farm than Nazarbayev had,” referring to the previous president.

The Kyrgyzstan government proposed on Monday a new procedure that would allow the regime to block websites accused by anyone of spreading fake news, even in cases where no evidence is provided. Outlets could get their website back only after they prove in court that the information was accurate.