Small power plants, defined as those that produce no more than 30 megawatts, have become an attractive investment in Armenia since 2001, when the government passed the Law on Energy Power requiring the national electric utility to buy up all the electricity they generate in their first 15 years of operation.

An extension of the lucrative guarantees is currently under consideration.

The investments are so attractive that environmentalists say at least one river—the Yeghegis -- is at risk because so many small plants have been built along it that fishermen say trout can’t breed and farmers worry they won’t be able to properly irrigate their crops.

A Hetq study of the shareholders behind these projects finds that many have ties to top government officials. And while top officials have the legal right to own the companies, they are barred from managing them. Critics say these plants are built without conforming to environmental standards, and at least one was built without environmental permits.

Parliament member Hakob Hakobyan and two brothers hold 54 percent of the shares in the largest hydropower project built so far on the Yeghegis River. Electricity is a charged issue in Armenia, which last summer erupted in major street demonstrations after proposed electricity price hikes of up to 40 percent. The government backed down and promised subsidies. Then, late in 2015, Russian businessman Samvel Karapetyan purchased the country's electric network through an offshore company.

Parliament member Hakob Hakobyan and two brothers hold 54 percent of the shares in the largest hydropower project built so far on the Yeghegis River. Electricity is a charged issue in Armenia, which last summer erupted in major street demonstrations after proposed electricity price hikes of up to 40 percent. The government backed down and promised subsidies. Then, late in 2015, Russian businessman Samvel Karapetyan purchased the country's electric network through an offshore company.

Hydropower is an important source of both clean power and income in poor, mountainous countries like Armenia, where it provides nearly one-third of the electricity. While most hydro still comes from Armenia’s 11 big plants—those producing more than 30 megawatts -- as of 2015 a total of 173 small plants were producing about 9 percent of the country’s power.

According to the Public Services Regulatory Commission (PSRC), 17 small plants that were built during the Soviet Union remain operational and were privatized by the new nation of Armenia between 1992-95.

Thirteen hydropower projects along a 47-kilometer stretch of the Yeghegis River have major shareholders from the politically elite.

Another 17 small private plants were built between 1998-2003. After the 2001 law passed requiring output to be purchased, construction skyrocketed, with 90 small plants built between 2004-2011. Since 2012, more than 50 additional small plants have been built or are in the planning stages.

The Yeghegis River system has proved to be a particularly popular place to build small plants. Eighteen have already been built on a 47-kilometer stretch of water in Vayots Dzor province in southern Armenia, and another six are under construction.

The small plants currently operating on the Yeghegis only produced about 41 megawatts in 2014, a tiny fraction of Armenia’s overall production of 685,000 megawatts. Yet that small amount of power comes at a high environmental price.

Two sons of Aghvan Hovsepyan, Armenia's former Prosecutor General, own shares in two hydropower projects on the Yeghegis River. Critics say the plants already in operation are sucking up most of the water in the river system, destroying traditional trout fisheries and depriving area residents of reliable access to water.

Two sons of Aghvan Hovsepyan, Armenia's former Prosecutor General, own shares in two hydropower projects on the Yeghegis River. Critics say the plants already in operation are sucking up most of the water in the river system, destroying traditional trout fisheries and depriving area residents of reliable access to water.

If three more applications for projects are approved by the PSRC, the entire 47 kilometers will be harnessed for hydropower projects. These plants are "run-of-the-river" projects that use small dams to capture and divert flowing water through turbines. But the large number of dams, and the way some are constructed, impede migratory fish.

According to government regulations, any river with dams must maintain a minimum "environment flow" of about 0.035 square meters/second, but the regulation is not enforced. Another legal requirement in natural streams is for “fish ladders” – a series of pools built like steps that allow migrating fish such as trout to bypass hydro installations and return upstream to spawn.

Some of the hydro projects have no fish ladders at all; others have ladders that are improperly built, so that they actually obstruct fish from their proper breeding grounds leading to lower populations.

Because they are private projects, statistics on profits are not public information. Due to their small size, those profits are in the thousands and not the millions. But the 15-year sales guarantee is attractive.

For example, one new project requires a US$ 1.5 million investment, of which 70 percent will be a seven-year bank loan. The investors estimate an annual gross profit of US$ 334,000.

Several members of the political elite have gotten in on the deals. They include:

Narek Sargsyan, nephew of President Serzh Sargsyan and son of Levon Sargsyan, former ambassador to Syria, Jordan, Tunisia and Algeria. Narek Sargsyan has a 50 percent share in a company building two hydropower plants.

Hayk Souvaryan, son of Hrant Souvaryan, chief of the Department of Financial Oversight for Armenia's National Bank, and son-in-law of former Prime Minister Tigran Sargsyan, is 100 percent owner of a company operating one plant. Hrant Souvaryan holds 15 percent of shares in another company operating a second plant.

Parliament member Hakob Hakobyan holds 34 percent of the shares in the largest of the plants built so far on the Yeghegis River. Two of his brothers own another 20 percent of the shares between them.

Mayis Mkrtchyan, brother and business partner of Bishop Abraham Mkrtchyan, Armenian Apostolic Church primate for the Vayots Dzor region, is the registered owner of a company that operates two plants and the director of a second company that operates a third.

Davit Ohanyan, son of General Hovik Ohanyan, who is in charge of implementing special assignments for the Ministry of Defense, is listed as 100 percent owner of a company that built a plant in 2013 and upgraded it in 2015.

Narek Hovsepyan, son of Aghvan Hovsepyan, Armenia's former Prosecutor General and currently head of the country's Investigative Committee, owns 50 percent of the shares in two plants. Another son, Misak Hovsepyan, owns 42.5 percent of the shares in a third plant.

Former Vayots Dzor province governor Sergey Bagratyan is 50 percent owner of a company that began building a plant in 2012 while he was still in office. Construction was temporarily halted after a Hetq Online article pointed out that the project lacked final environmental impact tests. The plant eventually received those results and is now operating.

Khajak Karayan is the deputy chairman of the State Committee of the Real Estate Cadastre. His brother Souren Karayan is a former Minister of Finance now serving as a deputy minister for International Economic Integration and Reforms. Their mother (Sofik Vardanyan) and uncle (Hrachik Vardanyan) own 60 percent of a company that operates one plant.

Zohrab Shahbazyan, father of former Central Electoral Committee deputy chairman Haroutyan Shahbazyan, is 50 percent owner of a company operating one plant.

When the Law on Energy Power passed in 2001, it guaranteed a market to small plants for their first 15 years of operation. In 2016, politicians are debating whether the guarantee should be extended.

“There is no decision now. The policy is implemented by the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, where discussions are now underway. The issue will be resolved in the coming months,” replied Sergey Aghinyan, chief of the development and monitoring department of the PSRC. The decision is expected by July 1.

For people who live along the Yeghegis River, the impact of environmental damage has far outweighed the advantages of more power generation.

Ghazar Ghazaryan is a 51-year-old resident of Shatin village who works at a hydroelectric plant. (Most plants supply about 10 jobs for local residents). "Fish are disappearing from the river," Ghazaryan said. "There were wild trout and other types of fish. They have disappeared because of those hydro plants. Tons of fish are gone.

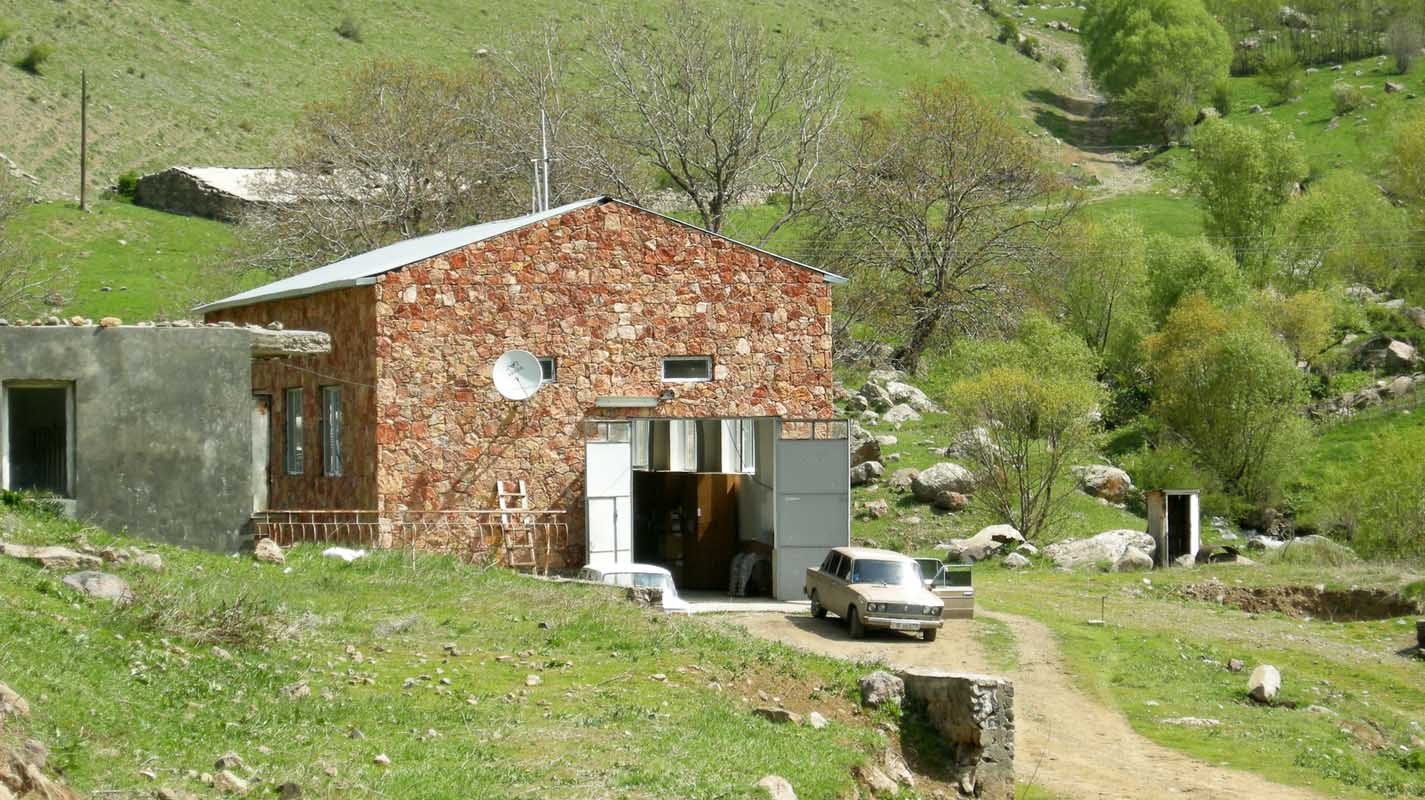

A pipe being installed as construction begins on another hydropower project on the Yeghegis River. In one 47-kilometer stretch, 18 small dams have been built and another six are planned. "Nature is drying up. If the river isn't flowing, the environment dies. Trees die. People are deprived of irrigation water."

A pipe being installed as construction begins on another hydropower project on the Yeghegis River. In one 47-kilometer stretch, 18 small dams have been built and another six are planned. "Nature is drying up. If the river isn't flowing, the environment dies. Trees die. People are deprived of irrigation water."

Local farmer Varazdat Nikoghosyan showed a reporter one of the hydro plants that is half-owned by the nephew of President Sargsyan.

"Because of these hydro plants, water is now scarce," Nikoghosyan said. "We can't water apricot orchards and grapevines. Out of about eight hectares, 80 percent is not cultivated."

During the peak irrigation months of July and August, the power plants are supposed to operate only during specified hours. But villagers near the plants say most of them operate 24/7.

Armenian Minister of Nature Protection Aramayis Grigoryan says the hydro plants help keep electricity rates low.

“Today, no matter how much we say that rates have gone up, if those hydro plants weren’t around, the rates would go higher," he said. "That’s why these operating plants must work efficiently and not harm the environment. If they do, then we wholeheartedly back them."

Grigoryan said the state has agreements with the plants about how much water they can use and much must bypass dams. Plants should also take into consideration irrigation needs. “We have to approach the issue correctly because water levels are decreasing. That’s evident. And if climate change occurs in the future, naturally water will decrease,” Grigoryan said.

The Ministry of Nature Protection, in conjunction with the EcoLur NGO, is implementing a program called “Green Passports” to jointly inspect hydro plants to see if operations need to be reviewed and changed.

According to data supplied by the ministry's Nature Protection Environmental Impact Monitoring Center, the temperature of the Yeghegis River rose 1 degree Celsius between 2009 and 2011. The center says this temperature hike is caused by the power plants and not by global warming. Oxygen levels have decreased. And in the lower stretches of the river, the native brook trout have all but disappeared.