After three years of digging, investigators in the United States had accumulated a mountain of evidence that they believed would seal the case against Kaloti Jewellery Group, one of the world’s largest gold traders and refiners.

The Dubai-based conglomerate was a key cog in the dirty gold trade, buying from sellers suspected of laundering money for drug traffickers and other criminal groups, a U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration-led task force determined. Kaloti often paid in cash — sometimes so much it had to be hauled in wheelbarrows — and wired money for suspect clients to other businesses, investigators believed.

In 2014, the task force recommended that the Treasury Department designate Kaloti a money laundering threat under the U.S. Patriot Act, a seldom-used measure known as the financial “death penalty” because it can freeze a firm out of the international banking system.

But Treasury never took action against Kaloti. Former Treasury officials said a decision on whether to move ahead was deferred for fear of angering the United Arab Emirates, a key U.S. ally in the Middle East. When attempts to convince the UAE to act on its own against Kaloti fizzled, the investigation was mothballed.

Investigators told the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) they were baffled and disappointed. Money laundering cases are extraordinarily difficult to crack and the U.S. has struggled to police the murky gold trade. With Kaloti, they thought they had a rare opportunity to send a message to the entire gold industry.

“I was incredibly frustrated,” one former official said. “What’s really sad is a lot of really, really good investigators, some really talented people, put a lot more time than they got paid for into trying to uncover a huge wrong.”

About This Investigation:

The FinCEN Files is a 16-month-long investigation by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, BuzzFeed News and more than 400 international journalists in 88 countries, including those from OCCRP and its network of member centers.

The U.S. investigation, which has never been reported before, came to light in a batch of secret bank filings that describe the flow of more than $2 trillion in suspicious transactions through the global banking system. JPMorgan Chase, Deutsche Bank, and other financial institutions flooded the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network with warnings about Kaloti, flagging thousands of transactions worth $9.3 billion that occurred between 2007 and 2015.

In some reports, the banks flagged transactions showing earmarks of money laundering. Several banks launched their own investigations and severed ties with the company — or said they planned to do so.

The documents, called suspicious activity reports, or SARs, were obtained by BuzzFeed News and shared with international journalists. Additional details about the government inquiry into Kaloti were confirmed in interviews with nine current or former law enforcement and other officials who spoke on condition of anonymity as they are not authorized to speak publicly about the case.

In a statement, a Kaloti spokesperson said the company “vehemently denies any allegations of misconduct” and has never “knowingly engaged with any criminal or criminal group.” Kaloti regularly conducts “all appropriate and required” due diligence and anti-money laundering checks, which have “never identified any such criminality, or its likelihood, amongst any active clients of Kaloti’s.”

The gold company has never been accused or questioned by any regulator or legal authority “about any material wrongdoing of the kind alleged or any other kind,” the statement added.

U.S. investigators said they never questioned Kaloti directly. Because the case did not result in charges or a Treasury designation, Kaloti never had a chance to see or challenge any of the evidence investigators had gathered.

A spokesman for the DEA said the Kaloti case is now closed and declined to answer questions about it.

A Family Business

Gold courses through the global economy, bought and sold by everyone from high-paid traders in London to street hawkers in Mumbai. For Munir Al Kaloti, who created the Kaloti Jewellery Group, it was the foundation of a business empire.

Al Kaloti fled Jerusalem to what is now the UAE in the 1960s, when it was still a dusty backwater with few paved roads. He got his start scavenging scrap metal and later imported goats for the then-ruler of Dubai, he once told a local news site.

In 1988, Al Kaloti opened a jewelry shop with his son-in-law, who had trained as a jeweler in Italy. It wasn’t long before they were buying gold. “People carrying scrap gold and gold from mines in Africa and Asia were coming in more and more and they are asking, ‘Who can handle this, who can buy this?’” Al Kaloti recalled in the interview. “So we said: ‘Why not?’”

Over the next quarter-century, Dubai grew into a major financial and business center. It also became an important hub in the gold trade, aided by low tax rates, proximity to Africa and Asia, and a reputation for secrecy.

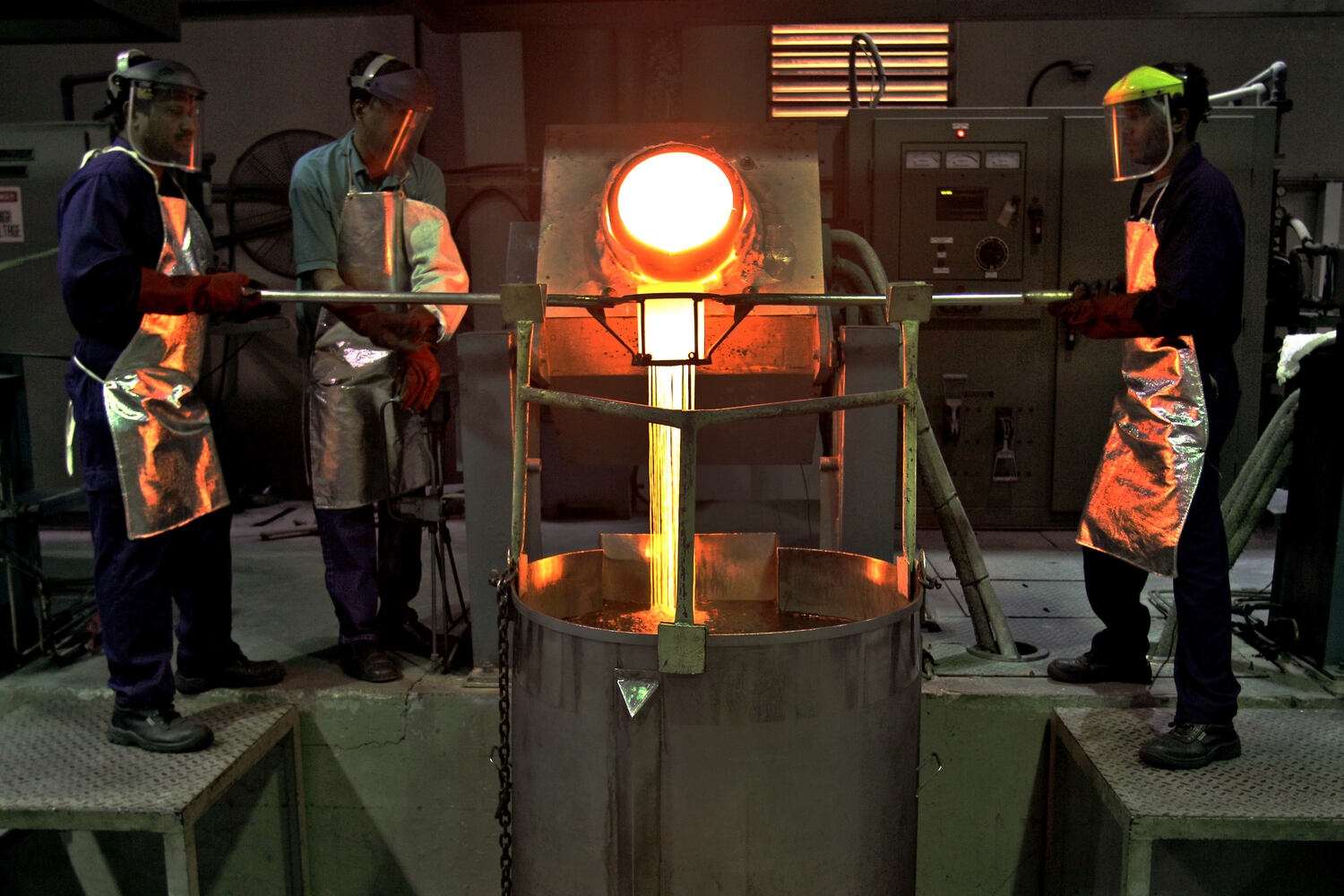

In 2000, the Kaloti Jewellery Group began trading gold bars. By 2008, it was refining its own. It soon became one of the largest gold trading and refining conglomerates in the Middle East, with branches also in Asia.

Kaloti also began to build business ties with major corporations, including the Swiss refiner Valcambi, according to anti-corruption advocacy group Global Witness. General Electric, Amazon, General Motors and dozens of other U.S. companies reported that Kaloti may have processed or provided gold as part of their supply chains in 2019, according to official filings.

Still, it remained a family business: Munir Al Kaloti’s son-in-law served as the general manager. One of his sons operated a gold buying office in a crowded Dubai souk.

Behind the scenes, however, Kaloti’s dealings had started to attract the attention of U.S. law enforcement.

Law enforcement has long seen the gold trade as a key vulnerability in the global fight against money laundering. Drug gangs and militant groups use gold to clean their cash and fund conflicts. In Peru, Latin America’s biggest gold producer and the world’s second-largest cocaine supplier, the illegal gold trade is now twice as big as drug trafficking.

“There is no better mechanism in the world for laundering money than gold,” said David Soud, head of research and analysis at I.R. Consilium, a consulting firm that specializes in resource-related crime. “It is concentrated, portable wealth, has essentially the same value anywhere in the world, and can be moved outside the global financial system.”

For these reasons, it is not unusual for a precious metal transaction to attract bank scrutiny. Gold companies are involved in roughly a quarter of all suspect transactions in the FinCEN Files.

But the leaked data show inquiries into Kaloti went beyond routine monitoring. As the U.S. investigation was gaining momentum, concerns about the company’s business practices also made headlines in the United Kingdom.

In 2014, a former partner at EY’s Dubai office reported Kaloti had accepted gold exported from Morocco disguised as silver, with falsified paperwork. Auditors at the global accountancy firm also discovered that Kaloti had purchased gold from Sudan — where the precious metal has financed a militia group under investigation for genocide — without properly vetting its suppliers, according to the former EY partner.

The following year, Kaloti’s refinery lost an important industry accreditation.

A Kaloti representative said the company has not been found by any regulators, international bodies, or auditors to have conflict minerals, “or even the likelihood of such,” in its supply chains.

Contacted by reporters, GE and General Motors said they do not source gold directly from Kaloti. GE said it had asked its supplier to stop dealing with the gold company. Amazon, GE, and General Motors said they are committed to having an ethical supply chain.

Operation Honey Badger

In late 2010, a DEA-led task force in central Florida started getting calls from agents investigating a money laundering scheme that spanned five continents as part of a law enforcement campaign called Project Cassandra.

An international criminal network was piping illicit cash from sales of Colombian cocaine in Europe to Africa, where it was combined with profits from used-car sales in Benin, prosecutors later alleged. Couriers connected to Hezbollah, a Shiite militant group and Lebanese political party backed by Iran, allegedly moved the cash to Beirut in exchange for a cut.

Beirut-based Lebanese Canadian Bank and money exchange businesses allegedly wired hundreds of millions of dollars to the U.S. for the criminal network to purchase still more used cars, completing the money laundering cycle. The network also sent funds through the bank to consumer goods companies in Asia to buy products that were shipped to South America and sold to pay cocaine suppliers.

In early 2011, the Treasury Department designated the Lebanese Canadian Bank a “primary money laundering concern” — the same financial “death penalty” that the government would later consider for Kaloti.

In Florida, the task force found that money sent to some of the used-car companies implicated in the Lebanese Canadian Bank case now appeared to be passing through Kaloti.

“Overnight the wire transfers you saw with Lebanese Canadian Bank and these other companies switched over to Kaloti, like a light switch,” recalled one former official. “We were like: ‘Who’s Kaloti?’”

Kaloti soon became one of the targets of a new probe, code-named Operation Honey Badger after the fierce mammal known for hunting pythons and cobras.

Investigators were especially interested in two Kaloti clients that they suspected were involved in laundering drug money using gold: Salor DMCC, based in Dubai, and a business in Benin called Trading Track Company.

Investigators noticed large wire transfers, sometimes more than once a day, from Kaloti to Salor. In payment details, Kaloti referenced gold trading and Trading Track. Salor often wired money to used-car dealers the same day, according to law enforcement records viewed by ICIJ.

“Kaloti was used to mask the source of a lot of those funds,” a former investigator said. “You had to follow the bouncing ball.”

Also a red flag for investigators was that Kaloti made cash payments worth millions of dollars to suppliers. Cash is difficult to trace, making it a preferred payment method for criminal groups. Documents viewed by ICIJ show that Kaloti paid Salor $414 million and Trading Track $28 million in cash for gold in 2012.

Kaloti declined to comment on its relationship with Trading Track and Salor. The company said it only accepts customers after conducting “robust due diligence” and any cash transactions “were not in any way improper.” A spokesperson added that Kaloti decided to stop dealing in cash for commercial reasons by August 2013.

A lawyer who acts for the owner of both Salor and Trading Track declined to identify his client. He did, however, tell reporters that neither company has ever taken part in money laundering, illegal, or unethical conduct, and that neither have never been charged with any wrongdoing. In a July interview, Trading Track manager Nemer Talj told ICIJ media partner Banouto in Benin that Trading Track transports gold for Salor that is entrusted to Kaloti for refining.

The task force began subpoenaing bank records, apparently putting the institutions on high alert. The FinCEN Files show a flurry of activity in 2012 and 2013 as banks rushed to tell authorities what they’d seen.

In 2012, Kaloti began transferring large sums from its Deutsche Bank accounts to Emirates NBD bank in Dubai. Agents for the company then began withdrawing so much cash from Emirates NBD that the money had to be moved in wheelbarrows, a former Deutsche Bank employee later claimed.

Deutsche Bank reported the withdrawals to U.S. authorities the next year, FinCEN Files show. The bank wrote that some traders on the London commodities exchange “seemed to be backing away” from Kaloti and that Deutsche Bank planned to do the same.

Deutsche Bank also reported its concerns to authorities in the UAE, including that U.S. authorities were investigating Kaloti. One of the UAE authorities, the Dubai Financial Services Authority, told ICIJ it did not have jurisdiction to investigate the allegations against Kaloti. The other, the UAE Central Bank, did not respond to requests for comment.

Around the same time, JPMorgan Chase said it had suspended commodities trading with Kaloti because the company had “attracted interest” from law enforcement and appeared to be engaging in “high-risk” transactions.

Emirates NBD kept Kaloti’s account open until at least August 2014, the filings show.

Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, and Emirates NBD declined to comment on ICIJ’s findings, citing confidentiality laws. Kaloti said it had engaged in roughly 75,000 transactions between 2012 and 2016 and said the number of SARs naming the company in the FinCEN Files was “statistically insignificant.”

The Whistleblower

On a visit to a Kaloti office in Dubai’s gold market in 2013, inspectors from the auditing firm EY noticed a stack of what appeared to be silver bars.

Munir Al Kaloti’s son scraped off the shiny coating to reveal gold. A Moroccan supplier had disguised the bars to evade export restrictions, according to an internal EY report later leaked by a whistleblower.

The EY inspectors were shocked. Buying gold from suppliers Kaloti knew had falsified paperwork could cost the company an industry accreditation known as “Dubai Good Delivery,” scaring away major international customers.

The auditors determined Kaloti had knowingly accepted as much as four metric tons of gold exported from Morocco with falsified paperwork. The shipments included gold from a criminal group that laundered $146 million in drug money through Kaloti, a later investigation by BBC Panorama and documentary production company Premières Lignes found.

Kaloti said in response to the auditors’ findings that it had properly vetted its suppliers before buying gold from them and “swiftly rectified” any “shortcomings.” The company told BBC Panorama it had conducted anti-money-laundering checks, it had not bought gold coated in silver, and it would “never knowingly” do business with an entity engaged in criminal activity.

The auditors shared their concerns with the Dubai Multi Commodities Centre, which runs the accreditation program and was set up in 2002 as part of a grand plan to make the emirate a world-leading hub for gold trading.

International standards call for gold buyers to scrutinize suppliers to ensure that they aren’t fueling conflicts or contributing to human rights abuses. But in many countries, including the UAE, enforcement is largely voluntary and left to industry accreditation programs.

Yet instead of taking away Kaloti’s accreditation, the DMCC in 2013 changed its rules to allow the company to keep specific audit findings secret, Amjad Rihan, a partner at EY’s Dubai office, later alleged. The DMCC disputes these allegations.

The DMCC removed Kaloti’s refinery from its “Good Delivery” list in April 2015, saying only that it had failed to meet standards. The move was largely symbolic as Kaloti continued to find buyers for its gold.

A Kaloti representative said there were no “valid grounds” to justify the removal of its refinery from the “Good Delivery” list and the decision “had nothing to do with Kaloti’s sourcing policy.” Kaloti said it has “evolved to comply with [regulatory] changes and has consistently met or exceeded all applicable regulatory requirements, consistent with industry best practices.”

In interviews with The Guardian and Global Witness, Rihan accused EY of participating in a cover-up of Kaloti’s failings and pushing him out of the firm. Earlier this year, a London High Court judge sided with Rihan and ordered EY to pay the whistleblower almost $11 million. The firm has denied any wrongdoing and is appealing the decision.

‘Tremendous Amounts of Illicit Value’

In August 2014, the DEA-led task force submitted a report to theTreasury Department detailing why investigators believed Kaloti and others, including Salor and Trading Track, were money laundering threats. The report listed Kaloti Jewellery International DMCC — which manages Kaloti’s physical gold business in the UAE — as the main target within Kaloti Jewellery Group.

The Operation Honey Badger team had reviewed more than 230,000 wire transfers and obtained warrants to search email accounts that contained over 450,000 conversations. They had traveled to Europe to interview sources. The U.S. military’s Special Operations Command and investigators from other agencies had also pitched in.

Kaloti and the other companies, investigators wrote, were “providing financial services for a variety of criminal organizations based throughout the world” and facilitating the conversion of dirty cash into gold.

“Together, they have established a significant capability to transport or otherwise transfer tremendous amounts of illicit value through the use of gold as a commodity, as well as bulk cash transfers and third party wire payments,” the report said, according to an excerpt seen by ICIJ.

The report alleged that Salor and Trading Track were among several “core entities” involved in laundering drug money.

A lawyer for Salor and Trading Track said the companies deny any allegations of wrongdoing and that “investigations that result in no finding of wrongdoing happen all the time, and the mere fact of an investigation is not probative of anything.”

A spokesperson for Kaloti said the company “categorically denies that it could have ever properly or reasonably been deemed a money laundering ‘threat’ or ‘concern’” and is “wholly unaware of alleged criminal connections” to Salor and Trading Track. Kaloti said that if it had been provided with evidence that any of its customers were knowingly facilitating criminal activity, it would have “immediately disengaged from those relationships.”

The Treasury Department conducted its own investigation of Kaloti, though it’s unclear if that included Salor and Trading Track. Before freezing the company out of the financial system, however, former Treasury officials said U.S. authorities wanted to check whether the UAE would handle the matter internally.

In 2015 and 2016, Treasury officials met with UAE authorities to discuss Kaloti. But the DEA-led task force lacked trust in the Emiratis and wouldn’t let Treasury share evidence, former investigators said.

Former U.S. officials say it isn’t totally clear why the “money laundering concern” designation wasn’t deployed. The Treasury Department has seldomly used the designation, which was created after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. In two decades, 26 foreign jurisdictions and financial institutions have been targeted — none were precious metals dealers.

“Should we have taken action? Yes, we should have,” said one former Treasury official, who nonetheless admitted the case was “never a slam-dunk.”

Although the Treasury Department didn’t take action, by 2013 three major banks had told authorities they had closed or planned to close accounts associated with Kaloti, the FinCEN Files and other records show.

A fourth bank, HSBC Hong Kong, waited until early 2016 to close Kaloti’s account, the filings show — two years after Rihan went public with his findings. HSBC declined to comment.

The Treasury Department, the Department of Justice and the UAE did not respond to questions about the Kaloti investigation. A spokesperson for the Special Operations Command said it could not comment on specific investigations. The DEA would only say the case is closed.

In a Sept. 1, 2020, public statement that alluded to ICIJ’s questions, the Treasury Department said that the “unauthorized disclosure” of suspicious activity reports was a crime and that it had “referred this matter” to its Office of Inspector General and the Department of Justice.

A spokesperson for Kaloti said that “had the U.S. Treasury Department really harbored concerns that Kaloti was in any way involved in money laundering, upon proper investigation... we are confident their concerns could have been easily allayed.”

‘Lip Service’ to the Rules

Kaloti had been a target of a U.S. investigation into alleged money laundering. EY was embroiled in a public relations crisis over accusations it helped cover up Kaloti’s alleged misdeeds. Major banks had closed company accounts. And an influential Dubai industry group revoked its seal of approval.

Yet Kaloti moved ahead with a plan to open a refinery in Suriname, a tiny South American country and former Dutch colony that the U.S. State Department warns is a transit hub for the continent’s cocaine.

The refinery was a joint venture with the government of Dési Bouterse, who was convicted of drug trafficking by a Dutch court in 1999. A national security consultant who visited Suriname in 2016 said he “found no evidence that the refinery exists.”

“Under these circumstances, the government can certify the exports of any amount of gold, real and fictitious, from a refinery that exists only on paper,” the consultant, Douglas Farah, wrote in a report for the Center for a Secure Free Society, a national security think tank.

Kaloti and Suriname’s government have disputed his findings and Kaloti published a letter from an auditor certifying that the Kaloti Suriname Mint House was operating between 2015 and 2017.

Kaloti appears to be thriving. Global Witness reported the DMCC allowed it to open a new refinery — MTM&O Gold Refinery DMCC — in 2017, despite removing Kaloti’s old refinery from its “Good Delivery” list two years earlier. (The DMCC told ICIJ that all applications for company registration are subjected to a “robust compliance process.”)

Global Witness, citing confidential sources, said that in 2018 and 2019, Kaloti bought Sudanese gold that may have funded armed groups. Those same years, the company sold roughly 20 metric tons of gold to Valcambi, the Swiss refining company, which is on both the Dubai and London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) “Good Delivery” lists, the advocacy group said.

Valcambi told ICIJ it would not confirm or deny buying gold from Kaloti. The company said it only makes purchases “where the company can fully ensure the identification of the origin of the gold” and does not accept gold from countries on sanctions lists, such as Sudan.

Kaloti told ICIJ that Global Witness’ findings were “not accurate,” saying it sourced gold in Sudan directly from artisanal and small-scale mines producing “non-conflict gold.” A spokesman for the LBMA said Valcambi had undergone two audits, including a “special audit” required because the company had obtained recycled gold from the UAE in 2018.

As of January 2015, Kaloti was a member of the U.S.-based commodities exchange COMEX, though the exchange would not confirm if it still is. The company is also a member of the Shanghai Gold Exchange’s international board and its branch in Turkey is listed as a member of the Turkish stock exchange Borsa Istanbul. Neither exchange responded to questions.

Meanwhile, experts say the UAE appears to have little interest in confronting the illicit gold trade. Billions of dollars’ worth of gold is smuggled out of Africa through the UAE each year, according to a recent Reuters investigation, depriving poor countries of much-needed tax revenue and allowing gold from conflict regions to enter the global economic system.

The Financial Action Task Force, an international anti-money-laundering watchdog, recently criticized the UAE for not doing enough to prevent money laundering.

“The ruling family pays lip service to following the rules, but it’s basically laissez-faire, anything goes,” said John Cassara, a former U.S. Treasury special agent who has written books on trade-based money laundering. “Money goes in, money goes out, and nobody enforces anything.”

In a statement, the UAE Embassy in Washington, D.C., said the country “is continually improving its own security—and those of its allies—by limiting and preventing illegal transshipments and money flows” and recently updated its anti-money laundering laws.

Current and former officials familiar with the U.S. investigation into Kaloti said the failure to take action against the company set a bad precedent.

“In my opinion, what is the risk factor? Being exposed?” one official said. “If you’re not being prosecuted or shut down, then what would stop you?”

Simon Bowers, Agustin Armendariz, Emilia Díaz-Struck, Will Fitzgibbon, Yao Hervé Kingbêwé, Emmanuel K. Dogbevi, Alloycious David, Sylvain Besson, Lisseth Boon, Delphine Reuter, Andrew Lehren, Emily Siegel, and Miguel Gutiérrez contributed reporting.