Jonny Ambarita takes a deep drag on his clove cigarette as he recalls the events of Sept. 16, 2019, when he says guards from a local paper company beat up several of his relatives then had him thrown in prison for trying to stop them.

That day had started like any other, as he and several members of his Sihaporas indigenous community, from Indonesia’s North Sumatra, set off to plant corn in a nearby village, on land their families have farmed for generations.

But soon, Ambarita said, security guards from PT Toba Pulp Lestari Tbk (TPL), a paper pulp maker owned by controversial billionaire Sukanto Tanoto, arrived on the scene and told the farmers to leave what they said was legally the company’s property.

When the group refused, Ambarita said the guards started pushing people and grabbing their tools, then hitting them. Several surrounded one of his relatives and began beating him. Ambarita said he tried to stop them — a court, however, later convicted him of assaulting a TPL employee after the company pressed charges.

“From the start we didn’t want any violence,” Ambarita told Tempo in a recent interview at the Sihaporas’ meeting hall, a type of boat-shaped wooden building called a Bolon house that forms the centerpiece of most villages in North Sumatra.

“We are indigenous people. Our way of life is peaceful.”

Many of the paper and palm oil companies that form Tanoto’s sprawling business empire — including those under Singapore-based Royal Golden Eagle (RGE) Group, which has assets in excess of $20 billion — have been accused of human rights abuses, from widespread land grabbing to deadly violence. Environmental groups say they have destroyed vast swathes of Indonesia’s rainforests and peat swamps, contributing to a noxious 2015 haze thought to have killed at least 100,000 people across Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore.

Tanoto holds the “dubious distinction of being the single largest driver of deforestation in the world,” according to Greenpeace.

Now an investigation by OCCRP and partners Süddeutsche Zeitung in Germany and Tempo in Indonesia shows how the billionaire secretly bought one of Munich’s most prestigious buildings in a deal worth close to 350 million euros.

Despite one of Tanoto’s companies being fined more than $200 million for tax evasion in Indonesia, and numerous reports accusing others of suspect profit-shifting practices, none of the professional services firms that worked on the deal say they notified German regulators about the sale.

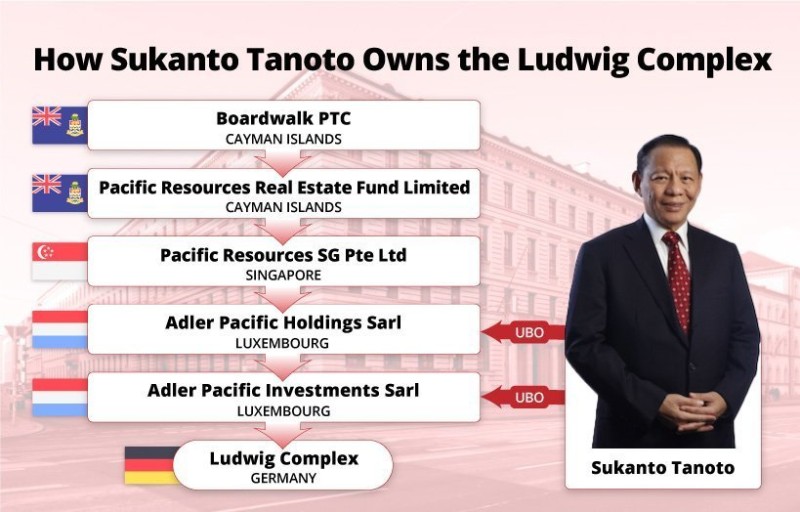

Documents show the tycoon’s ownership was carefully hidden through a chain of offshore companies in the opaque jurisdictions of Singapore, the Cayman Islands, and Luxembourg.

Tanoto’s purchase of the historic Ludwig complex in central Munich in July 2019 came just months after the European Commission agreed to phase out the use of palm oil in biofuels in the EU, arguing that it causes excessive deforestation in places where it is mass-produced, such as Indonesia.

"I think it is alarming that an Indonesian natural resources tycoon can apparently invest hundreds of millions of euros in European real estate through secrecy jurisdictions, without anyone really knowing,” said Mouna Wasef, researcher at Auriga Nusantara Foundation, an Indonesian conservation group.

“With so many of Tanoto’s businesses also relying on opaque tax havens for their trade, financing, and investment, this leaves the Indonesian authorities reliant on leaks from such jurisdictions to understand how the country’s natural resource wealth is actually spent.”

Ambarita and one of his relatives were arrested not long after the run-in with the TPL guards and eventually sentenced to nine months each in jail for assault. Four others from their village were placed on a police wanted list and have not been seen in the area since.

Ambarita said his community is still being harassed by representatives of TPL, which he accuses of poisoning the Sihaporas’ ancestral land.

“Our forests, our holy water, and drinking water sources are polluted. How can we drink people's feces, waste, and poison?” he said, his eyes reddening. “We just want to live peacefully in our traditional lands."

Royal Golden Eagle Group, through its offices in Singapore and Jakarta, did not respond to requests for comment.

In a written statement, TPL said the Sept. 16 incident had been instigated by villagers who planted crops illegally and then attacked company representatives. It denied that anyone working for the pulp company had intimidated or abused villagers.

The company also said it had received a land concession in a state forest area, and that the Sihaporas community had no recognized land ownership there. TPL said it was committed to “open dialogue” on such land claims, and to sustainable forest management across North Sumatra.

Tanoto’s Road to Riches

Sukanto Tanoto was born in Medan, Sumatra’s largest city, in 1949, the son of an immigrant from China’s Fujian province who ran a company that supplied spare parts to oil and construction companies.

The Eagle Has Landed

The Ludwig complex, in one of Munich’s most prestigious neighborhoods, is a world away from the humid jungles of Sumatra.

It sits on the corner of Ludwigstrasse, one of the four royal avenues built by Germany’s King Ludwig I in the 19th century, not far from the Bavarian State Library. Today the complex’s neoclassical facade hides approximately 27,000 square meters of office space, with Allianz and the Boston Consulting Group among its tenants.

In July 2019, land records obtained by Süddeutsche Zeitung show the complex was sold by Allianz Real Estate for a total of 348 million euros. Based on available transaction data, this would have ranked among the top office real estate deals in Germany in 2019. A few months later, KanAm Grund Real Estate Asset Management, which managed the investment, published a press release that described the buyer as a Singapore-based “family office” named Pacific Eagle. Tanoto’s name does not appear on either company’s standard business registration documents.

But in order to comply with European regulations on fighting money laundering, Luxembourg in 2019 introduced a new registry to reveal the names of people who truly control companies — known as ultimate beneficial owners, or UBOs.

Data from that registry, indexed by OCCRP as part of the OpenLux project to make it searchable, tells a more complicated story.

It shows that in June 2019 KanAm Grund incorporated two companies in Luxembourg: KanAm Grund REAM Lux 4 Sarl and KanAm Grund REAM Lux 5 Sarl. On July 23, they were renamed Adler Pacific Holdings Sarl and Adler Pacific Investments Sarl, respectively. (“Adler” means “eagle” in German.) Control of them was transferred to a company recently incorporated in Singapore named Pacific Resources SG Pte Ltd. Three days later, Adler Pacific Investments bought the Ludwig complex.

On paper, these two Adler companies are controlled by the Singapore company, which is controlled by two entities registered in the Cayman Islands — where beneficial ownership information is not public. However, Luxembourg’s registry lists Tanoto as the UBO of both Adler companies.

There is also evidence suggesting Tanoto’s Luxembourg companies, and their controlling shareholders, are directly affiliated with RGE, which controls many of the palm oil and pulp companies that have been accused of tax evasion and environmental destruction in Indonesia.

For one thing, Pacific Resources SG Pte Ltd shares the same address as RGE’s corporate headquarters in Singapore. Most of the directors of the companies involved in the Ludwig deal also have multiple connections to the Tanoto empire. Kian Lee Soon, a director of both of the Luxembourg companies, is the managing director of RGE subsidiary Pacific Eagle Asset Management, based on his LinkedIn profile and media reports.

Two of Pacific Resources SG Pte Ltd’s directors are also affiliated with RGE. Yong Ho Hsiang, who assumed directorship of the company in February 2020, is also a director of at least six RGE and Tanoto-affiliated companies. Eugene Ang Hui Tiong, a former director of Pacific Resources when it was established in July 2019, was the CFO at one of RGE’s principal businesses, and has been director of 13 companies linked to Tanoto. And the director of one of the Caymans entities, Pacific Resources Real Estate Fund Limited, Ng Yat Lung, is also a director of Hong Kong-based companies linked to RGE.

In a statement to Süddeutsche Zeitung, KanAm Grund said that Pacific Eagle had contacted the company in 2018. KanAm had offered a different building for purchase, but it was deemed to be “too small.”

The company said it provided two “shelf companies” in Luxembourg to facilitate the transaction, and conducted basic background checks but no additional due diligence, which was not required since the company did not play any part in the movement of funds.

Like Father, Like Son

Sukanto Tanoto’s eldest son, Andre, seems to share his father’s taste for expensive German real estate.

Due Diligence

It’s unclear where exactly the 348 million euros used to buy the Ludwig complex came from, or how much due diligence the lawyers, bankers, and other professionals involved in the deal carried out to establish the source of the funds.

“Many international services firms appear to have turned a blind eye to their responsibilities in this regard,” said Alex Cobham, chief executive of the Tax Justice Network.

“It is especially shocking that the firms involved seem happy to have taken their fees and raised no alarms in this particular case, where secretive investments into historic European buildings were made by someone whose companies have previously been fined hundreds of millions of dollars for tax evasion that relied on the use of anonymous offshore ownership vehicles.”

The Luxembourg office of Baker Tilly International, an international accounting and business advisory firm, which helped facilitate the Luxembourg company set-up, did not respond to requests for comment.

The Germany-based offices of law firms Clifford Chance, Eversheds Sutherland, and Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner, which assisted in the transaction, declined to comment, citing attorney-client privilege, although some stressed that they fulfilled all relevant due diligence requirements. BayernLB, a German bank that underwrote a loan for part of the purchase, refused to comment, citing bank secrecy laws, but said it had clarified the origin of the money.

Allianz Real Estate, which sold the property, and the German office of CBRE, which helped Allianz broker the deal, also refused to comment, but said standard background and anti-money laundering checks are conducted on all potential sales.

What is clear is the wide range of information on Tanoto’s dubious business practices that is freely available through a simple Google search.

In 2012, for example, RGE’s flagship palm oil company, Asian Agri, was found guilty of tax evasion by an Indonesian court and fined 2.5 trillion Indonesian rupiah (roughly $205 million). Five years later an investigation by the International Consortium of International Journalists showed APRIL Group, RGE’s paper and pulp company, had shuffled billions of dollars through companies in offshore jurisdictions from the British Virgin Islands to the Cook Islands.

A report published by a group of Indonesian and international NGOs in November 2020 also found that APRIL Group and TPL had misclassified pulp exports to understate their value, then resold the exports at a premium through companies based in offshore tax havens such as Macao. That allowed them to hide roughly $668 million in revenues between 2007 and 2018, avoiding an estimated $168 million in Indonesian taxes.

In a statement provided to Tempo, TPL said it rejected all allegations that it had engaged in tax avoidance, and that all exports were sold in accordance with their fair market value and applicable laws.

A German lawyer at a major global law firm, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid potential conflicts with industry counterparts, said Tanoto’s history and background meant that the proposed deal would not have passed his own company's audit.

"He would have had no chance with us", the lawyer said.

Germany’s Ministry of Finance has also warned of the ease with which potentially illicit investments can flow in the country’s real estate market, highlighting the ease of disguising ownership and the source of funds when making investments.

Transparency International estimated that in 2017 alone, at least 30 billion euros of illicit money was funnelled into German real estate via legal loopholes. Two years later, Germany’s Financial Intelligence Unit warned that suspected illicit transactions in the country had increased by 50 percent from the year before, saying the real estate market was “particularly vulnerable.”

Just a few months after Tanoto’s Luxembourg company bought the Ludwig complex, in November 2019, Germany passed laws mandating that real estate agents and notaries must declare suspicious transactions.

But Christoph Trautvetter, a German real estate expert and director at Netzwerk Steuergerechtigkeit, a network of NGOs focused on tax justice, said parties involved in property deals rarely file suspicious transaction reports.

“In theory, parties involved in real estate deals should conduct due diligence and report any suspicious transactions. In practice, this doesn’t happen unless there is concrete evidence of money laundering.”

Trautvetter said most service providers still interpret rules on reporting suspicious real estate transactions very narrowly, even after the recent change to the law.

“The transaction for the ‘Ludwig’ is a very good example of this problem,” he said. “It’s clearly suspicious by its size, its structure and the easily accessible allegations relating to the company’s questionable business practices. But the agents and notaries are in no position to judge — the question of legality ultimately needs to be determined in Indonesia,” he added.

Rainforests Destroyed

Despite pledging to improve their environmental track record, Tanoto’s companies are still destroying Indonesia’s rainforests and disrupting the lives of its indigenous communities.

Satellite imagery obtained by a consortium of researchers showed that one of the top suppliers of APRIL’s pulp mill in Sumatra has felled thousands of hectares of rainforest in Borneo since 2015, the year the company pledged to “eliminate” deforestation from its supply chain. Their report, published in October 2020, also revealed that this supposedly independent supplier has “significant links with the APRIL Group and its parent conglomerate, the RGE Group.”

Another study from 2019 found that more than 100 Indonesian villages and communities — mostly in Sumatra and Borneo — are locked in active conflicts with APRIL and its affiliates or suppliers. In total, the report estimated that more than 500 villages have been impacted by its operations.

“When it comes to APRIL Group, recent cases in the last few years clearly indicate that it has not been serious in implementing its sustainability commitments,” said Aidil Fitri, executive director of the Hutan Kita Institute, a Sumatra-based NGO that advocates for environmental preservation.

Woro Supartinah, the former coordinator of Jikalahari, another NGO from the island, agreed, adding: “They have only changed on the surface in an attempt to clear their names of past misdeeds. They still have a lot to work to do to convince us of their commitments.”

Indonesian authorities are also scrutinizing Tanoto’s business practices. In December, Tempo reported that tax and customs authorities were looking into allegations of profit shifting by TPL and APRIL Group that were raised in an investigation by a consortium of NGOs published in November.

Dian Ediana Rae, head of Indonesia’s Financial Transactions Reports and Analysis Centre, confirmed that his agency was investigating the information raised in the reports and had created a special task force for potential tax-related cases.

He also told Tempo that the agency, which has the power to scrutinize overseas investments by Indonesian nationals, was previously unaware of Tanoto’s purchase of the Ludwig complex.

Yet RGE has continued to expand internationally. One of its companies, Pacific Oil & Gas, is spearheading the development of a $1.2 billion liquified natural gas project in British Columbia, Canada, that was greenlit in 2016, despite campaigns against it by local environmental organizations.

RGE has also pledged hundreds of millions of dollars of new investment in its existing pulp mill and viscose fiber businesses in Brazil and China.

But the Sihaporas community in North Sumatra cannot escape the impact they say Tanoto’s TPL is having on their lives.

Ambarita said the traditional rituals they once used to protect their crops and respect nature have been disrupted. Workers keep tramping through the forest when the community is fasting in seclusion, fish used for one ritual are now scarce, and the village’s holy springs are polluted with pesticides.

“There is no longer a source of livelihood in the forest,” Ambarita said. “Before TPL arrived, we were much more prosperous.”