Philip Morris’s representative in Burkina Faso is a man with a reputation.

Known as one of the richest people in the landlocked West African country and its most “dynamic investor,” he’s said to sip whiskey with current President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré and to have been close to the previous one, Blaise Compaoré.

Dubbed the “boss of bosses,” he oversees a business empire that spans five countries and encompasses insurance, telecoms, trade, motorbikes, and lottery tickets — and also heads Burkina Faso’s influential National Employers’ Council. In 2020 he was on Jeune Afrique’s list of the 100 most influential personalities in Africa.

But that’s not all that Apollinaire Compaoré — long rumored to be related to Burkina Faso’s former president with the same last name — is famous for.

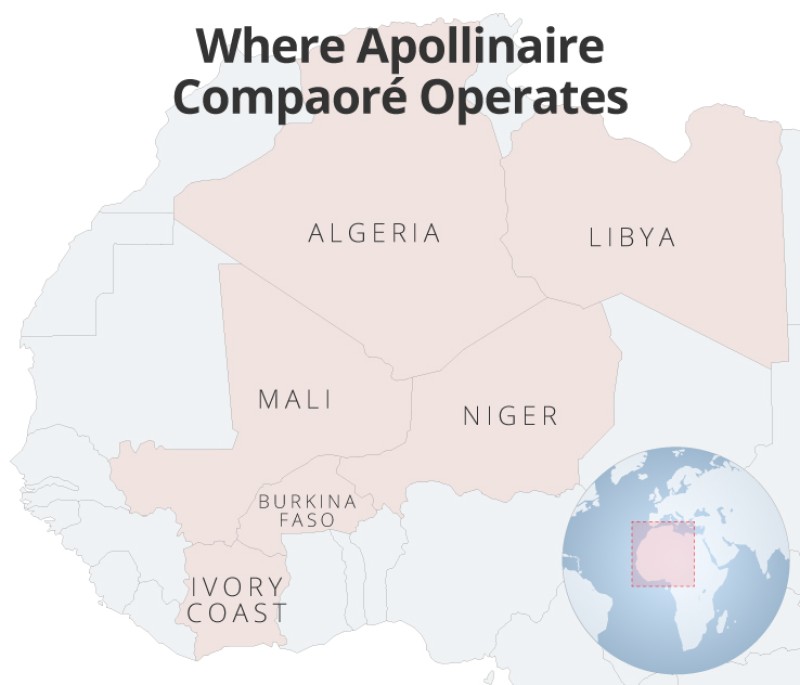

An investigation by OCCRP found he is widely known as a major West African tobacco smuggler, with an operation that stretches across six countries, from Ivory Coast to Libya.

The billions of cigarettes Compaoré moves through Burkina Faso finance armed groups and fuel a simmering conflict that kills hundreds of civilians each year. The Marlboros he runs through Niger and Mali into Libya helped to establish routes later used by the most notorious cocaine dealers and human traffickers in the Sahel.

This is no secret: one of Compaoré’s companies has been implicated in trafficking Philip Morris’s brands in three countries and he has been named as a smuggler by the U.N. Yet he is still Philip Morris’ man in Burkina Faso today.

Compaoré is a “crook. Very mean, without pity,” said his former business partner Ali Babati Saied, who estimates that the tycoon makes millions of euros each month from his tobacco smuggling operation.

“When you do business with him, be sure it will end in a lawsuit.”

Philip Morris International (PMI) confirmed that one of Compaoré’s companies is its sole distributor in Burkina Faso, but did not give more details on its relationship with him. A spokesperson said the company was unaware that its products destined for Burkina Faso are being illegally diverted to neighboring countries.

“We are not prepared to comment on decades-old, vague allegations by unnamed ‘former distributors’ and ‘another major tobacco company’ — groups with a clear competitive interest, or other incentive, to attack our company,” PMI said in a statement.

Allen Gallagher, a tobacco control researcher at the University of Bath, said Philip Morris is accountable for its people on the ground. The company settled allegations it was involved in the widespread smuggling of its own cigarettes with the European Commission in 2004 by paying $1.25 billion and promising to clean up its supply chain.

"Transnational tobacco companies like PMI are ultimately responsible for their products and where they end up, as is evidenced by the multiple lawsuits such companies have faced in the past when their cigarettes have been diverted from legal supply chains onto illicit markets,” Gallagher told OCCRP.

A lawyer for Compaoré, Kevin Grossmann, rejected the idea that Compaoré has any political influence and said his client respected the law.

“Mr. Compaoré has always reiterated his attachment to the law, as well as to transparency in all of his activities and those of his partners,” Grossmann said in a statement.

“Mr. Compaoré is an entrepreneur, and one of the main, if not the main, employers in the country. He is not a politician, and certainly not the holder of any power.”

Political Ties

Not So Clean and Careful

An official representative of a tobacco company is supposed to be a clean and careful operator.

On the face of it, Compaoré appears to be just that. He has described starting work at age five, planting millet and sorghum with his parents in the village near the capital where he grew up. Never having gone to school, he left home at 12 and walked 40 kilometers to the capital city to earn money selling lottery tickets.

Compaoré’s meteoric rise began in 1978, when he set up a company selling motor scooters. In the 1980s, he became the representative of Japanese tire manufacturer Bridgestone. In the early 1990s, he and several partners started an insurance company, Union des Assurances Burkinabè (Burkina Insurance Union). Then in 2004, he bought 44 percent of Telecel Faso, which became Burkina Faso’s third-largest mobile operator.

Within a decade, following a slew of legal battles, Compaoré sat at the top of a telecommunications empire with millions of subscribers across three West African countries. After expanding into banking and e-money, Burkinabè media report his group’s turnover is now around $300 million a year.

But Compaoré’s rise has been marred by allegations of corruption. And interviews and court documents suggest Compaoré has been involved in even dirtier dealings for decades. Businessmen as far away as Guinea know him as a tobacco smuggler.

Compaoré’s network moves “many, many billions” of cigarettes,” said his former business partner Said, whose distribution company briefly worked with the Burkinabè tycoon until their relationship soured and he successfully sued for unpaid debt in 2007.

“In Niger, they sell a number of cigarette brands, above all, Marlboros,” he explained. “They buy Marlboros and they sell them to Libya, to Mali, to Algeria, and Nigeria.”

Philip Morris says nothing about Compaoré in its public-facing material. He, by contrast, has said in media interviews that he started working for the tobacco maker in 1996, the same year he set up two distribution companies, SOBUREX and SODICOM.

SODICOM has been the sole distributor of Philip Morris products in Burkina Faso ever since. Former and current employees at SODICOM described a close working relationship between the two companies.

Compaoré has said his other company, SOBUREX, was created to re-export consumer goods from Burkina Faso. He told OCCRP those goods include Philip Morris cigarettes, though the Switzerland-headquartered tobacco company would not confirm if this was true.

That may be because SOBUREX has been implicated in contraband trafficking involving Philip Morris’s brands in three countries. A string of court cases and a report for the U.N. Security Council, which was covered in major French newspaper Le Monde, show the company has worked with notorious smugglers in the Sahel, connecting it to armed groups, terrorists, Nigerien politicians, and Burkinabè officials.

Raoul Setrouk, who used to work as a distributor for Philip Morris in Chad, said the tobacco major knew what was going on. He said both he and Compaoré were asked to invoice through a company linked to Phillip Morris’ partner, Rashideen, which he said was used to handle “sensitive operators.”

“PMI, before the 2000s, had chosen to centralize all sensitive markets in this region through its partner Rashideen, so as not to appear in the foreground,” said Setrouk, whose company is investigating bringing a class-action suit against PMI in New York about tobacco smuggling.

PMI documents obtained by OCCRP support his point, listing shipments of Marlboros sent to Burkina Faso and invoiced to Transafrica, a subsidiary of Rashideen, in 1996.

Files from Japan Tobacco International’s (JTI) intelligence operations show Compaoré’s illicit business was also well-known among PMI’s competitors. One describes shipments of cigarettes to Compaoré in 2009, connecting him to a wider web of smugglers in the Middle East.

“Alain arranged the sale of two containers of BC [Business Class cigarettes] to SOBUREX in Burkina Faso, a company owned by well-known cigarette smuggler Apollinaire CAMPAORE who has been dealing with [major tobacco trafficker] Nizar Hanna for years in smuggling of cigarettes in West Africa,” reads the report. (It’s unclear who Alain is, though he is mentioned in several JTI documents.)

Both SOBUREX and SODICOM are still registered as “active taxpayers” at the Burkina Faso Chamber of Commerce, though an official in the country’s tax authority said the revenue department has no record of either company paying taxes.

Ouedraogo said it’s possible Compaoré simply doesn’t bother to pay them, calling this a “form of oligarchy.”

Burkina Faso’s government declined to comment.

PMI said in a statement that it invests significantly in supply chain controls to combat the illicit tobacco trade, including track-and-trace technology, and conducts thorough due diligence on all of its customers and suppliers.

“Illicit trade is a scourge on society and the economy. It harms consumers by exposing them to unregulated products, deprives governments of tax revenue; moves through channels utilized by criminals for many types of criminal activity; and damages legitimate businesses — including our own,” said a company statement.

A ”Difficult” Man

‘Chérif Cocaine’

Among SOBUREX’s questionable business partners was an infamous Nigerien drug lord based in the northern town of Agadez.

Chérif Ould Abidine, popularly known as “Chérif Cocaine,” died in 2016. While alive, he was known for trafficking cocaine and other drugs through the Sahel, where his bus company 3STV, still operates.

He was connected to terrorist figures, among them Goumour Bidika, reported to be a key facilitator of terrorism and the drug trade in Agadez, and Chérif Kaffa, a member of MUJAO, an al-Qaida offshoot. Yet Ould Abidine enjoyed considerable political power in Niger, financing political allies and at times even holding a seat in the country’s national assembly.

Ould Abidine also allegedly moved Marlboros with Philip Morris’ representative, Compaoré, according to court documents obtained by OCCRP.

The case, filed in Abidjan in 2010, was Compaoré’s appeal against a series of financial disputes between the two men in Niger. Court documents say they moved “many” cigarette cargoes together, but their relationship soured because of a pay dispute over one shipment in 2002.

It’s unclear exactly how the lawsuit was possible, given that the dispute is over the profits of an illegal trade. Hassane Amadou Diallo, director of Transparency International (TI) Niger, said the tribunal was asked to arbitrate the dispute and so likely saw it as out of the scope of its role to question where the profits came from.

“Mr. Apollinaire Compaoré, trader residing in Ouagadougou, was selling in Libya through Mr. Chérif OULD ABIDINE, carrier trader domiciled in Agadez, cartons of cigarettes of various brands,” reads the introduction to an arbitration case between the two.

“Relations between the two partners deteriorated in August 2002, following a specific delivery involving, according to Mr. Appolinaire Compaoré, 1,319 boxes of branded cigarettes Marlboro, which would have been received by Mr. Chérif OULD ABIDINE and sold by him without him paying the revenues to his aforementioned supplier.”

The court decided to uphold rulings from previous cases between the two men, ordering Compaoré to pay ‘Chérif Cocaine’ nearly $300,000 in various commissions for Marlboro deliveries.

A lawyer for Compaoré declined to comment on his relationship with Ould Abidine, citing the need to “respect confidentiality.”

Diallo, from TI Niger, said Compaoré and Ould Abidine’s business in Libya, Algeria, and Niger was all illegal, because neither of them had a license to distribute cigarettes in these countries.

“It was certainly a huge quantity in terms of volume that traversed Niger to Libya and Algeria, and that was sold here, too,” he said.

Philip Morris’s own research acknowledges that the cigarette trade in the Sahel carved a route for the major cocaine flow that now makes its way through the region, a brutally destabilizing trade in an already war-torn region.

“The growth of a major cocaine trafficking route from South America across the Maghreb to Europe has exploited cigarette smuggling routes established in the late twentieth century,” says Illicit Trade in the Maghreb, a 2017 report commissioned by PMI.

Tobacco contraband is “the first cause of instability and, really of insecurity in northern Niger,” said Diallo from TI Niger. “It has had a terrible impact, because this smuggling developed mafia movements which weakened the army, the customs and finally occupied the Sahara, [leading to] the proliferation of guns and the occupation of this whole area by terrorist movements.”

In northern Niger, people on the ground described a well-organized trade in which drugs and illicit cigarettes move along the same network, which numerous studies and reports have shown finances terrorism.

Mahamad A., a trader from Agadez who used to be part of Ould Abidine’s network, said he would drive the merchandise from Niger to the border between Libya and Tunisia then hand it off to another group to be taken northwards.

“When we arrived there with the trucks, a group of people, Libyans and Tunisians, were waiting for us. We would all unload and put the boxes back onto other trucks,” said Mahamad, who asked that his full name not be used for security reasons.

"We are not afraid because our bosses watch over our security,” he said.

A spokesperson for a Tuareg independence movement that has controlled, off and on, much of northern Mali described a well-organized drug route from Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso through Libya to Egypt, saying the movement of contraband through Niger and further north across the border was secured by military and members of the intelligence.

PMI said it has no information that its products destined for Burkina Faso are being illegally diverted elsewhere.

“Should you have any evidence or intelligence that SODICOM SARL is involved in smuggling activities involving PMI branded cigarettes, we kindly request that you share details with us so that we can promptly investigate,” the company said in a statement.

Compaoré’s lawyer said SOBUREX “has always been, and always will be, transparent and exemplary. It fully supports a strict implementation of the peace agreement.”

All Roads Lead to Markoye

Perhaps Compaoré’s largest operation was a warehouse in Markoye, a town in northern Burkina Faso near the border with Niger and Mali.

The warehouse, where customs agents allegedly worked with cigarette smugglers from SOBUREX, was widely known. Salifou Diallo, the late president of Burkina Faso’s National Assembly, the country’s lower house of Parliament, referenced Markoye in a meeting in May 2017, but didn’t say who owned it.

“The latest information points to the importation of one billion euros per year — not dollars — of tobacco into Burkina Faso. But when we look at this figure, it means that all Burkinabè smoke at least 10 packs a day; but that can’t be," he said.

“The same source indicates that the largest tobacco depot in Burkina Faso is the town of Markoye, in the Sahel,” he added, describing how the tobacco is transported to the rebel-controlled towns of Gao and Kidal in northern Mali, then on to Algeria, Libya, and “Arab countries.”

He estimated that two thirds of the tobacco imported into Burkina Faso is destined to be sold to drug-trafficking groups, “who in turn feed terrorism.”

“For the passage of these cargoes of cigarettes, they are forced to hire the services of those who know the tracks, who have turned into terrorist groups,” he said, connecting the smuggling in Markoye to brutal terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso and Ivory Coast.

Michel Badiara, a parliamentarian, was assigned to make an informal fact-finding mission to Markoye to investigate. He told OCCRP he never made the trip, or learned who ran the warehouse, but said that its existence is “no secret.”

He said the goods were designated as “transit” until they reached Markoye, meaning they weren’t subject to Burkina Faso’s tobacco-control provisions.

A customs agent who worked at the Markoye warehouse for four years told OCCRP he personally escorted trucks carrying cigarettes from Ghana and Ivory Coast. He said the smuggling operation, which he estimated received 30 to 40 trucks every few months when he was there, was facilitated by customs and police.

“The Markoye warehouse is not an official warehouse, it was like a mafia at the top of the state,” said the agent, who asked not to be named out of fear for his safety. Compaoré “made his fortune out of these cigarettes,” he added.

He said the warehouse was a transfer point where big shipments were broken down and released to smugglers to take north. He said they often came in vehicles terrorist groups often use in the desert, which he and a Markoye resident described as brand new pickup trucks.

“The vehicles that terrorists use in the north, you know vehicles that are easier to move around in the north — this kind of vehicle was used to come [to the warehouses],” he said. “They came to load in the stores, but generally they went up towards Algeria.”

“They are armed groups, or smugglers. Anything that is contraband. It's to buy guns, it's to buy gold. We tell ourselves that it was certainly armed groups that were handling this affair,” he said.

The Markoye warehouse has supplied billions of cigarettes that have been smuggled north, many of which have fallen into the hands of terrorists. This trade continued even when Philip Morris was paying the European Commission tens of millions of dollars in fines for smuggling, and even after the warehouse ostensibly shut down when the area was seized by jihadists in 2018.

The U.N. Security Council’s Panel of Experts found Compaoré’s SOBUREX sent American Legend cigarettes to the Markoye warehouse as recently as that year, when customs stopped policing the area after one of its officers was murdered.

A former Compaoré associate, Sidien Agdal, who is now a politician in Niger, told the panel the American Legends were bound for onward transport through Mali to Algeria and Europe.

“He also told the panel that American Legend cigarettes were kept in a customs depot in Markoye and usually taken by smaller dealers who trafficked them straight to Mali,” it said in a 2019 report, which determined the cigarettes moved north from Makoye “under escort of Malian armed groups.”

Agdal told OCCRP that he is no longer in the tobacco business, but offered to provide more information in exchange for weapons. OCCRP declined the offer.

Compaoré’s lawyer said SOBUREX respected Burkina Faso’s customs laws and requires customers that re-export its products to comply with the laws of the destination countries.

“The management of the distribution of cigarettes by Soburex has always been conducted in compliance with relevant legislation and the greatest transparency,” the lawyer said in a statement. “Any breaches by Soburex’s customers cannot be attributed to it.”

The entire zone of Markoye is now frequently under attack by groups tied to al-Qaida and to the Islamic State. Ismaël Traoré, a civil society leader in Markoye, said trucks rarely haul cigarettes through the region now, though Marlboro remains the most popular brand.

Apollinaire Compaoré remains the representative of Philip Morris in West Africa.

Additional Reporting by Sandrine Gagne-Acoulon.