The daughter of a top Moldovan judge lived large in London thanks to 1.6 million lei (US$ 130,000) that was channeled through two companies involved in the Russian Laundromat -- a massive money laundering scheme that pumped billions of dollars through Moldova from Russia.

Most of the money went to a real estate agency to cover the rent of a luxurious apartment not far from Buckingham Palace in which Mihaela Muruianu lived while studying in London. A smaller portion was deposited directly into her personal bank account.

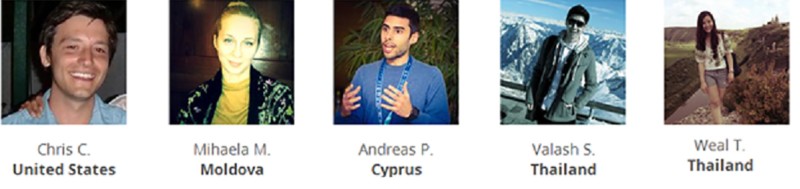

She is the daughter of Judge Ion Muruianu, the former president of Moldova’s highest court.

The money was funneled from Russia through a series of ghost companies registered in the United Kingdom (UK), and its precise origin is not known.

But the payments raise questions about the Muruianu family’s access to significant wealth, given that their total declared income for 2012 stood at 752,000 lei ($62,000) -- a little less than the $66,000 estimated cost of the apartment for a single year.

When reached for comment, the judge and his daughter both said they knew nothing about the Russian Laundromat. Mihaela Muruianu further denied any knowledge of the ghost companies from which the transfers originated.

“I do not know the kind of activity these companies are involved in or who their founders are,” Mihaela Muruianu said.

Money from Ghost Companies

The Laundromat scheme was elaborate, involving the fraudulent transfer of massive sums out of Russia and into the European Union with the help of corrupt Moldovan judges.

The judges would order Russian companies to make large payments to fake firms registered in the UK in repayment of fictitious, previously arranged “debts.” The Russian money was thus channeled into the world financial system via legitimate court orders. (For more on how the scheme worked, see: The Russian Laundromat Exposed)

Reporters from RISE Moldova, an OCCRP partner, traced the transactions that delivered money to the Muruianu family. In July 2012, Judge Valeriu Gisca of the Riscani district court in the Moldovan capital of Chisinau ordered four Russian companies to pay $500 million to Westburn Enterprises Ltd., one of the core players in the Laundromat scheme.

Later, some of the money was transferred to a bank account belonging to Ronida Invest LLP, which then redirected $102,000 to Liberton Associates Ltd. (Neither of these “ghost companies” seemed to conduct much business; between them, they reported administrative costs of less than $5,000).

A few days later, Liberton transferred the $102,000 to Knight Frank LLP, the London office of a global real estate firm that arranged for the rental of Mihaela Muruianu’s apartment on Fulham Road.

Posh Digs

In response to the inquiries of an incognito RISE Moldova reporter, Knight Frank provided details about the luxurious apartment in which Mihaela Muruianu and her husband lived in 2012-2013.

The residence is in the historic area of London, near Buckingham Palace, the official residence of the British monarchs, and within walking distance of Hyde Park and the Thames River.

The $180-per-day apartment is described in its advertisement as having two bedrooms, a bathroom, a living room, and a kitchen. The building has a сoncierge service, according to a page on Knight Frank's website which has since been removed.

It is also a 15-minute walk from London Imperial College, where Mihaela Muruianu studied “science, innovation, entrepreneurship and management,” according to her LinkedIn account. Currently, the tuition for the course attended by Judge Muruianu’s daughter amounts to £27,000.

Mihaela Muruianu told reporters that the money paid for the apartment was part of an agreement her father made with a Moldovan businessman.

“The essence of the deal, from my father's words, is that my potential employer pays a part of [my] rent expenses ... and after my studies, and three years of internship in a British company … which will be completed in 2019 ... I agree to work in the Republic of Moldova for a period of five years, mainly in the banking sector,” she said.

“The deal was concluded in my absence and it was confidential, so I am not aware of the rest of the details, including the businessman’s identity.”

Mihaela’s father, Judge Muruianu, initially told reporters that his daughter had paid her rent herself.

“You have the wrong information,” he said, laughing. “[Mihaela and her husband] pay their monthly rent on their own, from the money they earn.”

Judge Muruianu later admitted that there had been an agreement with a businessman, but did not reveal who he was.

“According to the agreement, the parties don’t have the right to disclose details to third parties,” he said. “We have not talked about it to anybody. From public sources I knew that this person was a shareholder of several banks and a wealthy businessman.”

Paid from the Laundromat for her “audit consultancy services”

In February 2014, Mihaela Muruianu benefitted from an additional $28,000 of Laundromat money. This time, the funds went directly into her personal account at HSBC in London. The transfer was carried out by another British shell company, Carditeks Commerce LP, and its purpose was officially described as a payment “for audit consultancy services.”

Asked about the sum by reporters, Mihaela Muruianu could shed no light on the transfer.

“I haven’t had any relationship whatsoever, including a contractual one, with the companies you mentioned, and I haven’t provided any services to them,” she said. “Your mentioning … of the so-called ‘Laundromat’ [relating to the origin of the money] has a depressing effect on me,” she continued, “and it’s obvious that I was not aware of these circumstances.”

After her initial response, she stopped talking to reporters.

At that time, Mihaela Muruianu was promoting a start-up called Lapkin, which sold laptop keyboard covers. It has since gone defunct. As recently as May of 2017, her LinkedIn account stated she was working as an innovation coordinator at Digital Catapult Centre, a non-profit digital consultancy in the UK. She has since deleted her account.

Dubious connections

Liberton Associates Ltd., the Laundromat company which paid Mihaela Muruianu’s rent in London, had previously been involved in a major scandal related to Energoatom, a Ukrainian energy producer.

The complex scheme, which goes back 20 years (and is still being fought over in court), involved $23 million in payments to companies connected to the notorious Moldovan businessman Veaceslav Platon. The money was sent allegedly to pay off Energoatom’s debts. However, the debt was fake and the paperwork fraudulent.

According to Russian court documents examined by RISE Moldova, Liberton was one of 11 companies involved, eight of which were connected to Platon.

Notably, Judge Muruianu was a member of the panel of judges on Moldova’s Supreme Court which, in 2004, upheld a decision by a lower court to enforce the Russian court order.

Platon was recently convicted of embezzlement and money laundering and sentenced to 18 years in prison on an unrelated matter.

From judge to Supreme Court president

Judge Muruianu has 27 years of experience in the judiciary. He started his magistrate career in 1990 at a Chisinau court and became its president in just two years.

After the Communist party won Moldova’s 2001 parliamentary election, Judge Muruianu's career took an upswing. He joined the country’s highest court, the Supreme Court of Justice, in 2004, and took over its presidency in 2007.

After the Communists lost the 2009 election, Moldova’s new government dismissed Judge Muruianu on several occasions for “failure to perform official duties,” but he was returned to office twice on the decision of the Constitutional Court. In 2012, Judge Muruianu transferred to the Chisinau Court of Appeals, a lower court, where he works today.

When Mihaela Muruianu began her studies in London in 2012, her family’s income stood at 752,000 lei ($62,000) for the year, according to the family’s mandatory declaration. The following year, the family’s revenues rose to 845,000 lei ($64,700), but dropped to 802,000 lei ($51,000) in 2014.

During this period, according to his income declarations and information in the property register, Judge Muruianu opened, and then closed, several lines of credit at Moldindconbank -- the same bank through which the approximately $20 billion of Laundromat transactions were conducted. There is no further available information about the family’s sources of income.

This is not the first time Judge Muruianu has courted controversy. On several occasions, journalists have discovered properties owned by the judge which he had not declared in his mandatory income statements.

In unrelated matters, he has referred to the journalists as “rabid dogs.”

According to Transparency International (TI), an anti-corruption watchdog, Moldova is the most corrupt country in south-eastern Europe, ranking 123rd out of 176 on the group’s Corruption Perceptions Index. In its 2015 report, TI noted that Moldova’s judicial system has been “compromised by the non-meritocratic promotion of judges and by selective justice applied to political competitors.”