The Russian Laundromat, a large multi-billion money laundering machine uncovered last year by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), used the services of several residents of a small town near Kyiv. But while they controlled billions, the directors of the British and Russian companies that comprised the scheme never even knew of their power – or their involvement. In 2014, OCCRP reporters in Moldova noticed that judges in their country were issuing numerous rulings of the same kind: Russian firms and Moldovan citizens would be ordered to pay a considerable sum of money to an offshore company to settle a previous debt that it had guaranteed on behalf of another company.

The involvement of the Moldovan citizen ensured that Moldovan courts would have jurisdiction, and Moldovan judges consistently ruled that the Russian companies must pay—legalizing the transfer of dirty money out of the Russian Federation. The money was then transferred from the same Moldovan bank to the same Latvian bank safely within the European Union.

The Laundromat’s complex cleanse-and-spin cycle made up of dozens of offshore companies, banks, fake loans, and proxy agents moved $20 billion from Russia to the EU from 2010 to 2014. While its impossible to know exactly where all the money came from and ended up, its most likely that they elaborate system was set up to hide money stolen by corrupt politicians or earned through criminal activity.

As it turns out, Ukrainian citizens played an important role in the scheme. They were involved at various stages of the operation, mostly as phony directors of the web of fake companies.

The Bosses

Three Ukrainians involved in the Laundromat are neighbors in Myronivka, a small town of 12,000 residents located 100 kilometers from the Ukrainian capital of Kyiv. In 2014, the budget of Myronivka and the surrounding district barely exceeded US$ 10 million.

The money washed in the Laundromat makes the region’s annual budget seem like pocket change.

Four years ago, the British firm Valemont Properties filed a lawsuit in the Moldovan capital of Chisinau demanding the return of US$ 180 million from a London-based company called Seabon Limited. The debt was guaranteed by the Russian firm Laita M Ltd., headed by Myronivka resident Oleg Bilonog, 41.

Bilonog had been a worker in a local construction company, Rayagrobud. In Soviet times, the company employed 700 people. Now it doesn’t produce anything, says the construction company's director Vasyl Dikhtyar, who told OCCRP journalists he remembers Bilognog clearly.

"He was a simple guy, working there without any arrogance or pomposity. He was a little bit younger than the others from (his construction) team, but he was working as a stonemason and was a good specialist."

-Dikhtyar says

It is hard to see how this former stonemason’s company could guarantee nearly US$200 million of debt, regardless of the court’s ruling, unless the debt existed only on paper.

Reporters wanted to ask Bilonog about that, but he no longer lives at his registered address on Gorkogo Street. His parents answered the door, and said their son had moved to Russia in 2006.

Bilonog’s mother says her son is firmly established in Russia. "I know that he is working at a building site, he has family there, he's registered there, he lives there," she says.

His parents then called Bilonog in Russia and handed OCCRP reporters the phone. He told them he was not the head of the Laita M company.

In the house next door to the Bilonog family lives another Ukrainian involved in cross-border Laundromat transactions. Oleksiy Romaniuk, 28, is listed as a director of that same Seabon Limited which, according to the Moldovan court, owes more than a billion dollars.

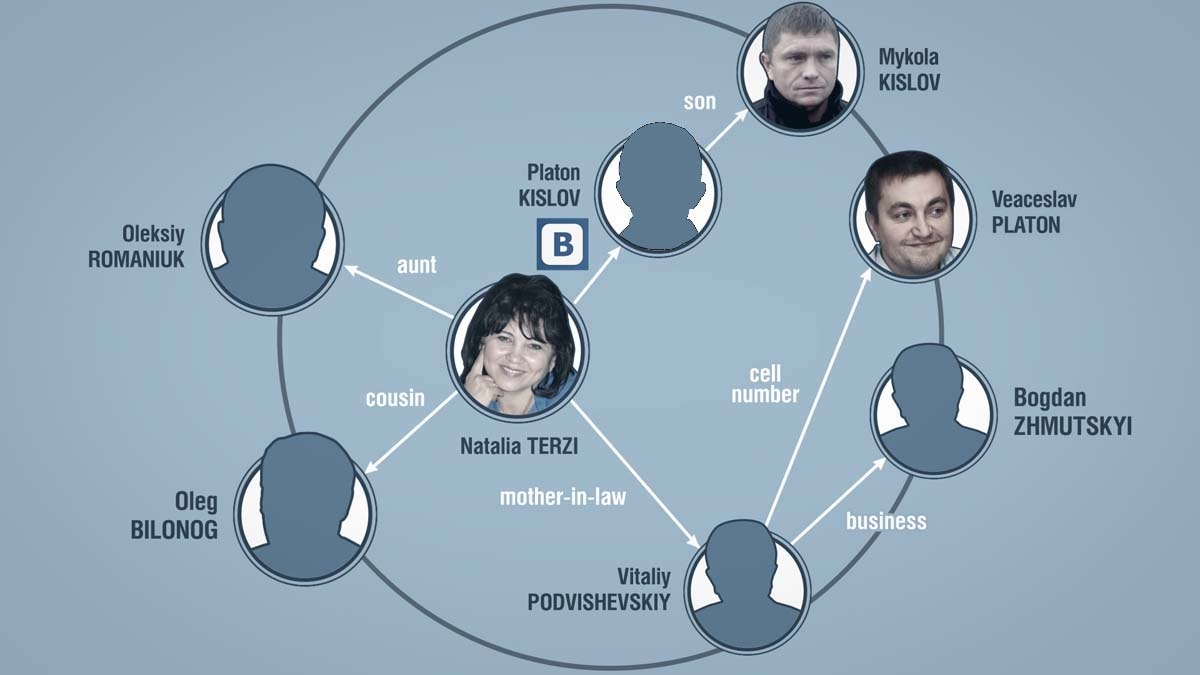

The OCCRP reporters also talked to Bilonog’s cousin, Natalia Terzi, who is also Romaniuk’s aunt by marriage.

Romaniuk "graduated from the Trade and Economic University. I know that he worked in the Coffee House (a chain of coffee shops). I have not seen him for five years, and I don't know where he is now," Terzi says.

On Jan. 16, Terzi promised to contact her nephew, and pass him OCCRP’s questions. Nearly a month later, Romaniuk has still not commented on his overseas business

Mykola Kislov, the third Myronivka citizen involved in the Laundromat, was a legal representative of the U.S. company Albany Inc. In 2013, he agreed to repay the British firm Mirabax Investments a debt of US$ 580 million.

Kislov, 38, also lives on Gorkogo Street. However, nobody was home when OCCRP reporters visited, and the neighbors claimed they didn’t know him.

Reporters located Kislov’s resume online, which says he works as a cook in various sport clubs. When contacted, Kislov declined to comment on this story.

In Kyiv, OCCRP reporters met attorney Bogdan Zhmutskyi. He is listed as a representative and lawyer for the British company Mirabax, which has filed lawsuits to recoup hundreds of millions of dollars in fake debts, including those from Kislov’s Albany Inc. When reporters showed Zhmutskyi documents with his signature, he quickly scrawled his name on a paper napkin but then immediately hid it, not letting them take a closer look. He claims his signature was forged and says he does not know the three Myronivka proxies.

And yet documents from the Spark database of companies and searches on social networks indicate Zhmutskyi’s business partner is connected to the Myronivka millionaires.

In the early 2000s, Zhmutskyi founded the Industrial and Construction Company Ukrtransbud. His partner in this company was another Ukrainian, Vitaliy Podvishevskyy.

Podvishevskyy is married to Karina Terzi, Oleg Bilonog’s niece and Natalia Terzi’s daughter. Podvishevskyy also owns 99 percent of the company Konsultek, which is the sole shareholder of Soyutek Development - another Russian firm involved in the Laundromat scheme.

Yet another company that Podvishevskyy heads - the service cooperative Evans, which manages real estate - shares a cell phone number (+380503565595) with Jet Business Limited, a Ukrainian company that until recently was owned by Moldovan businessman Vyacheslav Platon. Platon is a shareholder in Moldincombank, the Moldovan bank used in the Laundromat's transactions.

Reporters called Podvishevskyy for comment. He denied he shared numbers with Jet Business Ltd although he admitted to having known Zhmutskyi for a long time. But further questions were not answered.

“As I understand you have received an order. Someone has sponsored you to pour dirt on me. Tell me who pays you?” Podvishevskyy asked the reporter. “Good-bye, forget this number, and it is better for you not to meddle where you should not be.”

Alexander Sugonyako, the president of the Association of Ukrainian Banks, believes the Laundromat scheme had to originate high in the government.

"This is a common theft, criminal offense, carried out in very large scale. The whole state is robbed. It is clear that these things cannot be done without the assistance of the highest state authorities."