When the oil rigs arrived in central Yemen three decades ago, Sheik Salem Saeed Alhowtally’s community did not know what to expect.

“Otherwise we would have protected ourselves,” the tribal dignitary, who lives in an agricultural zone surrounded by oil wells, told reporters in an interview.

Over the years, he recalled, he watched workers for a foreign oil company dump barrels of what looked like drilling waste into open pits near where his tribe lives.

Birds and animals would come and drink the water, he recalled, but when they started dying the company put up a fence around the pits. This has done little to stop heavy rains from sweeping the contents down the valley into Raseb, where Alhowtally’s community lives in the heart of one of the country’s oil-producing regions.

“When flash floods hit, we see a blackness in the water that resembles oil,” Alhowtally said.

Like other communities living near Yemen’s oil fields, his tribe has paid a high price while private and state companies have made billions of dollars. Since oil was discovered in Yemen in the 1980s, attempts to hold polluters to account have floundered amid war and the fracturing of political power.

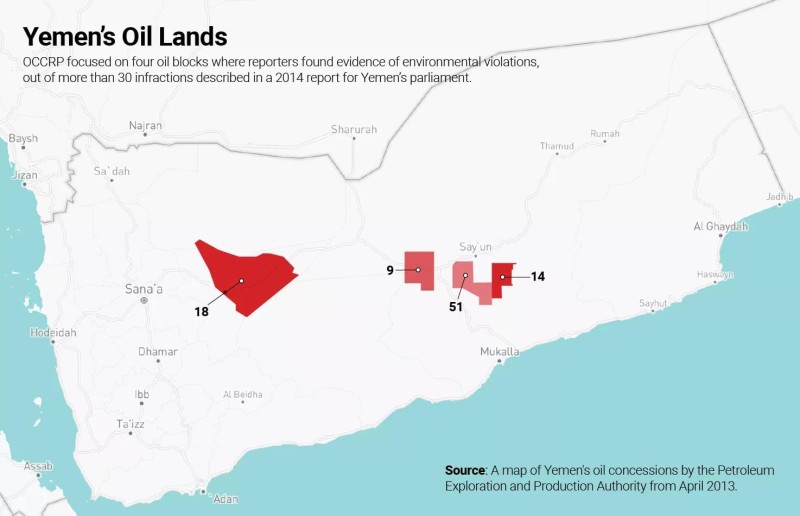

An unpublished 2014 report commissioned by Yemen’s parliament, obtained by OCCRP, describes over 30 environmental violations carried out by more than a dozen oil and gas companies and their affiliates between the boom days in the early 2000s and the country’s descent into civil war in 2014.

Delivered to lawmakers as the conflict was erupting, the 2014 document has been gathering dust ever since. While many of the foreign oil companies have left, state companies that took over the industry have allegedly continued the devastation, according to oil industry experts, environmental officials, and Yemenis who live in oil-producing regions. In one case, the former head of the country’s environmental agency is suing a state oil company over the ongoing health impacts on people in the region.

“When regulatory oversight in a country is weak, companies get comfortable,” Derham Abu Hatim, the Ministry of Oil’s director of security, safety, and the environment, told OCCRP, referring to the lax supervision he said prevailed when oil companies first arrived in Yemen.

The 147-page report was written by an environment professor who was commissioned in the face of growing complaints about the oil and gas sector. Citing photographs, analyses of water and air samples, inspections, and citizens’ complaints, it describes incidents involving over a dozen international energy firms, local companies, and contractors.

The Canadian oil company Nexen — which until 2015 operated near Alhowtally’s community and has since been bought by China’s CNOOC — is accused of “recklessness and wilful negligence in polluting the environment with drilling fluids” in the parliamentary report. CNOOC did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the report.

The scale and repetition of the pollution “indicates intentional persistence in committing crimes against the environment,” the report concluded. Images of rig sites operated by Nexen at the time, located close to where Alhowtally lives in an area known as Block 51, show large amounts of dark liquid pooling across the desert sands.

Instead of properly treating the drilling waste, the Canadian company chose the “cheap and easy” option of simply mixing it into the soil and leaving it in open pits, Abdulghani Gaghman, a geological expert who worked for Yemen’s Oil Ministry in the early 2000s, said after reviewing details in the report.

“Nexen was careless about the way they disposed of or treated the drilling fluids,” said Gaghman, who monitored the work of oil companies during his time at the ministry. “And it is not only Nexen, but other companies working in Yemen.”

Ali Dabhani, the chief of the environment ministry's hazardous waste department, who reviewed the report before it was submitted to parliament, told OCCRP it showed not only the "recklessness and negligence” of the oil companies, but also the failure of Yemeni authorities to properly enforce regulations.

The country’s civil war has further complicated efforts to clean up the industry, said Yasmeen al-Eryani, who researched the topic in a 2020 report for the Sana’a Centre for Strategic Studies.

“Today conditions to enact accountability mechanisms are even more challenging, she told OCCRP.

After propping up Yemen’s government for decades, oil profits are now a source of revenue for the country’s warring factions. Those like Alhowtally are still living with the fallout. Like many in the region, he blames oil pollution for falling crop yields in his area and a rise in illnesses such as cancer and kidney disease.

“Our land has never been like this,” he lamented. “It was fruitful and now it has become barren and is of no use.”

Yemen’s Oil Ministry and Environment Protection Authority did not respond to requests for comment.

Polluted Waters

After oil was discovered in Yemen in the mid 1980s, a flurry of foreign companies descended on the country to scoop up concession areas carved out by the government. These “blocks” were handed out under production-sharing agreements which gave the companies rights to explore for oil on the condition they share royalties with the state.

At the peak of production in the early 2000s, Yemen was pumping 450,000 barrels per day. Before the war broke out, oil and gas revenues accounted for about three quarters of the state budget.

Nexen, which was previously known as Canadian Occidental Petroleum, was one of the first companies to find oil in 1991 and by the early 2000s was operating two blocks in the province of Hadramawt. It wasn't long before locals started to feel the effects.

The parliamentary report details how, in March 2008, an estimated 4,500 barrels of oily water leaked out of a drainage well on Nexen’s main concession area, Block 14.

Tribal leader Omar Saeed Ba’abaad remembers the spill. The polluted waters kept flowing for four days, and covered multiple farms, the 75-year-old told OCCRP during a visit to the area. The land has never been the same, he said.

“We used to produce 40 to 50 bags of wheat per season. Now we only produce 10 and buy the rest.”

Pictures in the parliamentary report show a slick black substance seeping across a tree-speckled valley. The authors describe it as “produced water” — liquid which is pumped to the surface alongside oil and is often contaminated by hazardous chemicals, some of them radioactive.

Companies across Hadramawt committed “flagrant environmental violations” when disposing of this type of waste, the report noted.

Produced water can be disposed of by reinjecting it back into the reservoir it came from, but this must be done carefully to avoid contaminating groundwater sources, explained Gaghman, the geology expert. The risk is particularly grave in Hadramawt, which sits above Yemen's largest aquifer.

“Produced water is poisonous, it cannot be used for humans or animals or agriculture unless [it has been through] major treatment, which oil companies avoid because it’s costly,” Gaghman said.

After Nexen left Block 14 in 2011, the state-run company that took over found the site in disarray, according to an arbitration case that Yemen’s oil ministry filed against the Canadian company and its partners in Paris two years after Nexen’s departure.

Yemen accused the firms of carelessly reinjecting produced water and failing to monitor if it had contaminated groundwater. Nexen admitted it had pumped the wastewater just below a freshwater aquifer for five years in the 1990s, but said it caused no environmental damage.

The ministry also described finding dangerous and deficient wells, waste dumped or burned in the open, and a broken incinerator that hadn’t been fixed for years. Though Yemen’s environmental laws were weak, the oil ministry argued in the International Court of Arbitration, a Paris-based institution which resolves commercial disputes, that Nexen and its partners had failed to meet the basic standards set out in its contract.

While some of the accusations were dismissed — the claim about causing pollution with produced water was deemed beyond the statute of limitations — the tribunal ordered Nexen to pay nearly $10 million to fund the replacement of the failing waste incinerator, other faulty equipment, and the costs of an environmental impact assessment it had failed to carry out before leaving the block.

For Yemenis who live near the country’s oil fields, the impact of pollution can be measured in more than dollars. Scientific studies have shown living near petroleum fields is associated with an increased risk of certain cancers.

Data from the Hadramawt Cancer Foundation — in the region where Nexen operated — show cancer cases nearly tripled between the early 2000s and 2015. Its director, Dr. Walid Abdullah Al-Batati, said that while no studies prove oil pollution caused the spike, the areas near the oil blocks “have the highest rates of cancer in comparison to other governorates.”

Ba’abaad, the tribal leader whose land was tainted, blames oil pollution for the cancer that killed his brother a few years ago.

“Our health and our lands are all destroyed because of the [oil] companies,” he said.

State Company Takes Over

In Yemen’s other main oil-producing region, roughly 35 kilometers from the city of Marib, sits Block 18, where Dallas-based Hunt Oil Company discovered the first oil in Yemen in 1984.

The parliamentary report describes various violations during Hunt’s 20-year tenure, from the emission of dangerous levels of nitrogen oxides in the air to the improper storage of hundreds of barrels of expired chemicals. Hunt was also found to have buried chemicals in a hole in the desert alongside drilling waste, and allegedly attempted to bury a “not insignificant volume of excavation waste products” at another site before being halted by local officials.

Hunt declined to comment on the report.

Hunt exited Block 18 in 2005 after parliament refused to renew its lease for the concession. But the state-run Safer Exploration and Production Operations Company that took over is accused of carrying on its legacy.

In 2018, Abdulqader al-Kharraz, then-chairman of the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) received a complaint that the state company had buried dangerous chemical waste from one of its processing units in the desert. Less than a year later, the EPA received another complaint that the company had been improperly storing chemicals, leaving them exposed to the elements, in a threat to the surrounding area.

After multiple efforts to seek cooperation from Safer failed, Kharraz filed a lawsuit in 2020 accusing the company of burying hazardous chemical products and drilling waste, and seeking compensation on behalf of dozens of cancer patients.

The scientist backs his claims with an analysis of 65 soil samples he took from various landfill and trash sites in Safer-run Block 18 and two neighboring blocks over the course of several years. Lab tests revealed they contained volatile hydrocarbon particles and metals that can cause cancer — such as chromium, copper, nickel, and lead — at levels above international limits.

In one of the samples, the level of lead was more than 120 times higher than the international standard used in the laboratory, while zinc was 32 times higher.

Kharraz also distributed a 2020 questionnaire to a random sample of 51 people in Harib, a city near the blocks he sampled, and found nearly two thirds suffered from cancer and more than 17 percent had chest and respiratory diseases. The incidence of brain cancer was highest among children.

In comments to OCCRP, Safer denied burying any dangerous material in its site or violating Yemen’s environmental law, which punishes intentional pollution that damages the environment with up to 10 years in prison. The company also denied that its operations were harming the population’s health, though it declined to comment on Kharraz’s lawsuit specifically.

The company said that since taking over Block 18, it has taken measures to protect the environment, such as lining waste pits and protecting water supplies with better cementing of underground pipes.

Resuming Operations

While most foreign companies left Yemen or paused production after civil war broke out, some have resumed operations. In October 2021, OCCRP reporters visited one area known as Block 9 in Hadramawt, which is operated by Calvalley Petroleum Cyprus.

Oil Industry a ‘Red Line’

Kharraz’s legal proceedings against Safer have stalled in Yemen’s courts since 2020, with the company’s lawyers challenging technical details. The original judge on the case recused himself that year, and other judges have refused to reopen the case.

In September 2019, a few months after Kharraz made his second complaint to Safer, he was replaced as chairman of the EPA. When he brought the case against Safer the following year, the company’s lawyer requested the prosecution investigate him for disturbing the peace and harming the public interest.

The scientist says he eventually fled Yemen after threats that started as “advice” from friends escalated to verbal intimidation, including from a government official who spoke to his father.

After Kharraz left the country, a Yemeni army tank shelled his home. Kharraz, who was compensated for the damage, believed he was targeted for standing up to the government. The army confirmed the compensation, but OCCRP could find no evidence he was specifically targeted.

"Powerful people in government and oil companies protect their interests by preventing effective scrutiny of the sector," said Kharraz, who now spends time moving between countries.

Mohamad Salem Mojawar, another former senior EPA official who led the agency’s operations in the oil-rich governorate of Shabwa, said he too was replaced after trying to expose pollution in his region.

In 2020, his office started documenting contamination carried out by both foreign and local oil companies operating in the area. These included failure to stop, and properly remediate, frequent and large oil leaks from a pipeline operated by the state-run Yemen Company for Investment in Oil & Minerals (YICOM). YICOM did not respond to requests for comment.

Mojawar’s office was soon “warned by some authorities [against exposing] pollution, which has stayed for many years as a red line, shielded from scrutiny,” his agency wrote in a statement in April 2022.

Two months later, Mojawar penned two letters to the region’s governor alleging that his envoy had instructed the EPA not to pursue legal action against oil companies or damage their reputations. Later that month, Mojawar was fired. Shabwa’s governor did not respond to requests for comment.

Meanwhile, “the problem of oil pollution has not been solved,” Mojawar told OCCRP in March. “The polluted soil is still there and when rain falls, floods move it to agricultural land.”