In public, Papua New Guinean Prime Minister James Marape has taken a hard line on Don Matheson, an Australian consultant at the center of a multi-million-dollar offshore payments scandal that caused an uproar in the Pacific country.

A joint investigation by OCCRP and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) in March revealed that Matheson played a central role in suspicious offshore payments to senior officials at the time they awarded major international contracts to operate the country’s biggest ports.

The report made headlines in Papua New Guinea (PNG), and prompted Marape to order official probes of the state-owned PNG Ports. Under pressure, the prime minister also denied claims made by Matheson that he enjoyed close ties to Marape and his family.

Asked by the country’s opposition leader in March about his links to Matheson, Marape told parliament that he had merely played “one or two rounds” with the Australian businessman at a golf course in the capital, Port Moresby.

“[I] play anyone who walks into that club, who's a visitor or new person, I invite them. ‘You wanna have a golf with me?’ I invite everyone [to] come for a walk at the golf course. Part of my health regimes anyway. So Mr. Matheson plays one or two rounds of golf with me,” Marape said.

But new evidence shows the relationship was closer than the prime minister has claimed. Marape and Matheson appear to have made high-level introductions for each other in both PNG and Australia, according to interviews and official documents obtained by OCCRP, the ABC, and Inside PNG.

One newly obtained series of letters appears to show that in early 2021, Marape personally introduced Matheson to PNG’s powerful State Enterprises Minister William Duma — the same man the prime minister has now tasked with looking into the current scandal.

Duma then sent a letter of recommendation to help Matheson pitch for lucrative contracts to develop state-owned land in Port Moresby. It is unclear if Matheson was successful in obtaining the business.

Duma told an ABC journalist that he would not answer any media inquiry from the Australian public broadcaster unless it was accompanied by written permission from Australia’s communications minister “to inquire into domestic issues of another country.”

“The alleged notion of conflict of interest which you have assumed does not arise here,” Duma wrote in an email.

Reporters also found that, the following year, Matheson attempted to arrange a meeting between Prime Minister Marape and a senior Australian politician, Queensland state opposition leader David Crisafulli, during a 2022 visit to Australia.

Neither Marape nor Matheson responded to questions sent by reporters.

The head of the PNG chapter of Transparency International, Peter Aitsi, said evidence of previously undisclosed ties between Matheson, Marape, and his senior minister Duma, could undermine public confidence in the government’s review into the offshore scandal.

“If there is proof that there is a relationship between [Matheson and Duma], then, rightfully so, Mr Duma should be removed” from overseeing any government review, he said.

“Investigating Other Engagements”

The new evidence that Marape and his key minister had undisclosed contact with Matheson comes as PNG police have launched an international investigation into the Australian businessman and dealings at PNG Ports, OCCRP and partners have learned.

Joel Simatab, the criminal investigations chief of the PNG police, told OCCRP and partners that national authorities have launched a wide-ranging criminal probe with the assistance of Australian law enforcement and Interpol.

“As part of the investigation, PNG Police will be investigating other engagements involving Don Matheson in PNG, apparently due to him allegedly paying bribes to PNG Ports Corporation officials,” Simatab said.

Australian Federal Police declined to comment. Interpol did not respond to questions.

OCCRP and ABC’s previous investigation revealed that a Singapore company owned by Matheson had received roughly US$4.35 million in unexplained payments from a Manila-based global ports operator, International Container Terminal Services (ICTSI), around the time it secured a lucrative contract to run PNG’s two busiest freight terminals. The company’s account was then used to pay for apparent benefits for two senior officials at the state-owned ports operator, PNG Ports, including a racehorse and medical equipment.

One of those officials, PNG Ports CEO Fego Kiniafa, was murdered last September. Police are treating the killing as unrelated to the corruption investigation. The revelations about Kiniafa have prompted questions for Australia, which had negotiated a $434 million ports funding deal with the late CEO as part of its efforts to counter China’s growing assertiveness in the region.

The Pandora Papers files also contain information on nine other contracts that Matheson said he had secured in Papua New Guinea. OCCRP and partners found signs that one of those contracts, a master plan for a new provincial capital, was won via a bidding process that may have been tilted in Matheson’s favor.

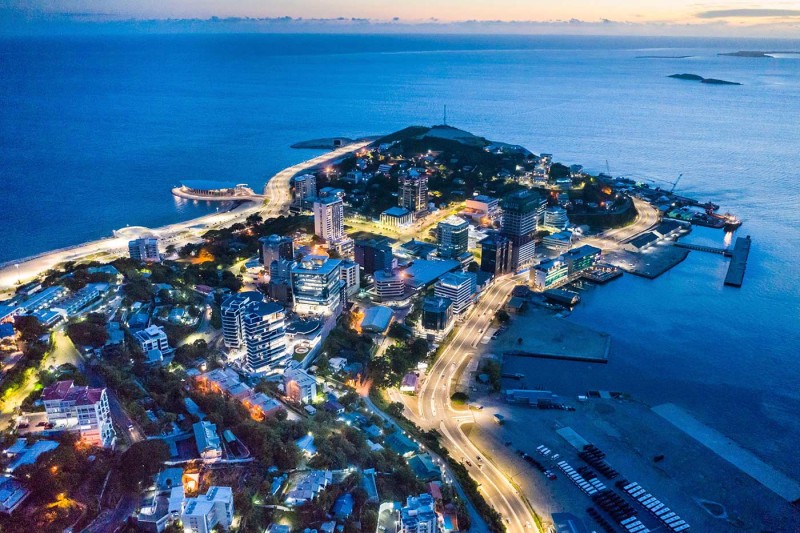

“The Best Piece of Real Estate in the South Pacific”

Official letters obtained by OCCRP and partners show that Prime Minister Marape apparently boosted Matheson’s business prospects in PNG by introducing him to State Enterprises Minister Duma.

Matheson wrote to Duma on May 3, 2021, to express interest in his company, CSG International, playing a role in the commercial redevelopment of an old wharf site in Port Moresby belonging to PNG’s state holding company, Kumul Consolidated Holdings.

“I would like to take this opportunity to formally acknowledge and thank you for making time available to meet me on Tuesday April 29, 2021 following my introduction to you by the Prime Minister, Hon. James Marape, MP about my role in town planning and design,” Matheson wrote to Duma.

The Letters

Duma forwarded the letter on to Kumul Consolidated Holdings’ managing director at the time, Isikeli Taureka, in early June. In a cover note, Duma described the contents of the letter as “self-explanatory.”

“I suggest that Kumul Consolidated Holdings enter into discussions with CSG in relation to the proposal,” he wrote in the note.

Taureka wrote back to Matheson shortly afterwards. He did not commit to working with CSG, but said he was open to further discussions with Matheson.

Records obtained by OCCRP do not show whether Matheson obtained the contract, and Kumul Consolidated Holdings did not respond to reporters’ questions about the project. Taureka was dismissed as head of the holding company in October 2021 for what the prime minister said was poor performance.

Taureka confirmed to OCCRP that he had received the letter from Duma suggesting a discussion with Matheson, but believed he needed to first find out more about the Australian businessman.

“I asked Don to present himself to receive his credentials but he didn’t show up,” he said, adding that he did not know if Matheson was ultimately given the contract.

However, in two separate interviews with the ABC last year, Matheson implied that he had indeed won the contract. He called the old wharf site “probably the best piece of real estate in the South Pacific at the moment.”

“We've got a lot of Australian government departments that if we could get them as tenants in some of the buildings we can have created here, that would underpin the development.”

Matheson said he had met with the managing director of Kumul Consolidated Holdings, David Kavanamur, to discuss “our planning report and… we’ve nailed it.”

“He's thrilled, the PM's thrilled, our challenges will be to get it through density planning,” he said.

He said he had “nearly completed” his work on the old wharf site and “after I complete my contract there, I’m entitled to talk” about it.

Matheson also attempted to carry out at least one high-level introduction for Marape in Australia. He told the ABC last year that he attempted to set up a meeting for Marape with Queensland Opposition Leader Crisafulli during a visit to Brisbane in October.

A spokesman for Crisafulli, Rob Morrison, confirmed that Matheson did contact his office seeking a meeting for Marape. But he said that the meeting did not take place because of a clash in their schedules.

Matheson “sent [Crisafulli] a text saying the PNG PM is in town and is keen to meet,” Morrison said, but “their diaries never lined up.”

‘We Didn’t Tender for It’

Police did not specify which of Matheson's other PNG projects they were examining in their probe, and the country's government agencies typically do not publish details of public contracts.

However, OCCRP and partners found records of at least nine other contracts the businessman said he had won from PNG state companies and government agencies between 2013 and 2019.

The details of the deals were contained in documents Matheson filed when becoming a client of Asiaciti Trust, one of 14 offshore service providers whose internal data was leaked as part of the Pandora Papers, millions of files leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with media partners around the world, including OCCRP.

The contracts included plans for a new hospital outside of Port Moresby, the redevelopment of an old military barracks, a housing estate and industrial area for PNG Ports, and master plans for two towns. OCCRP is not alleging any wrongdoing in those projects.

However, reporters did find evidence that a third town master planning contract — a 4.9-million-kina (roughly US$1.4 million) deal to design a new provincial capital city in PNG’s remote highlands — was won via a tender process in which his competitors say they didn’t even know they were taking part.

Signed bid documents filed by Matheson with Asiaciti show that the tender board of Hela, then a newly created province, awarded a contract in September 2016 to CSG International to produce a master plan for the town of Tari. The town sits in a national electoral district held by Prime Minister Marape since 2007, but there is no evidence he played a role in the deal.

On paper, CSG won the bid by offering a cheaper price than two other Australian bidders. EJE Architecture, a firm based in the Australian city of Newcastle, is listed as having bid 5.4 million kina (around $1.5 million). MG Group, a property consultancy on Australia’s Gold Coast, was put down for 6.1 million kina (around $1.7 million).

Both companies had worked as subcontractors for CSG on other projects in PNG. But they denied to reporters that they were involved in the Tari bid.

“We didn’t tender for it,” said Matthew Grbcic, the principal of MG Group. “I don’t even think… I did any work on that particular job.”

Michael Rogers, a director of EJE who worked on the company’s PNG projects with Matheson, said that he doesn’t recall bidding, although he said there was a small chance that any records of a bid may have been thrown out as part of a regular purge of office files.

“I'm 95% certain that [the bid] won't be ours and it sounds like it's dodgy,” Rogers said. “So everything points to being that it wasn't ours and it was falsified.”

William Bando, the former provincial administrator who signed off on the contract with CSG, said he did so “based on advice from my technical staff.”

Bando, who now serves as the MP for a nearby electorate, said that it was Matheson who had “provided the bids from overseas bidders.”

He said he was later “instructed to terminate Matheson’s contract” when there was a “change of political leadership” in the province. He did not elaborate.

Hela province paid CSG International for at least some of the project, Pandora Papers files show. In November 2016, CSG invoiced Hela Province for 330,000 kina (around $94,000) for an initial “desktop report” for the city plan. The invoice appears to have been paid by the following February: a copy of CSG’s bank statement for that month shows the provincial administration made a payment of 330,000 kina on February 6, 2017.

.jpg/daf5f209c20846c8dcd2295cae2a00ae/kenyan-aladdin-sep24-(1).jpg)