Boško Buha, a senior Serbian police official, was walking to his SUV in a restaurant parking lot in June 2002 when the Belgrade night was pierced by gunfire. Buha was shot in the chest and stomach and later died at an emergency clinic.

The police general, who had recently left his department to advise the police minister, had no bodyguards because he had no known enemies. A video showing him bleeding out next to his car while waiting for an ambulance shocked the nation.

Investigators quickly identified two cell phones that were frequently used near Buha as he had gone about his business — a clue that his assassins had been trailing him for days.

Tapping those phones led police to an unexpected enemy: a terror cell directed by Group America, an international drug trafficking organization with clear ties to Serbian and Montenegrin security services and reputed ties to the CIA.

Perhaps most shocking of all was the motive for the murder: Politics.

Buha was the first victim in a planned terror campaign aimed at panicking Serbian citizens and destabilizing the reformist national government, which had taken over from Slobodan Milošević after the dictator’s ouster.

Group America and its associates in government hoped both to gain political influence in Serbia and to take control of drug sales, cigarette smuggling, and other criminal activities across the region, prosecutors would later say in court papers.

An Experienced Killer

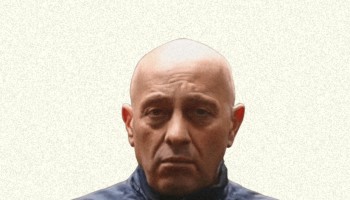

The leader of the assassination cell that allegedly killed Buha was identified as career criminal Željko “Maka” Maksimović, according to criminal records gathered by OCCRP and KRIK.

In 1995, Maksimović was showing a gun to a friend on a Belgrade street when they were approached by a police officer. Maksimović shot the cop four times. He later claimed he had mistaken the officer for a robber and was never prosecuted for the death.

By the time of the Buha hit in 2002, police knew Maksimović and his cell were part of Group America. Just a year earlier, a gang insider known as “Lucky” had described in detail the group’s leadership, its drug networks, its murders, and its strong ties to various mob bosses.

Lucky told police that Maksimović and others were responsible for many unsolved murders in Serbia in the 1990s, during the Milošević era. Their victims were said to include not only rival mobsters but also two officials: Police General Radovan “Bluto” Stojčić and Zoran Kundak, a member of the JUL political party.

To this day, the only known evidence tying Group America to those officially unsolved killings comes from Lucky’s statement. But despite the information he provided, the group has never been the subject of a major police investigation in Serbia.

A Bigger Plot

After killing Buha, his assassins made a fundamental mistake: They kept using the cell phones they had employed while stalking their victim.

Court records show that investigators were listening as the men used the phones to plan murders of other high-level officials, businessmen, and rival criminals. Though they used code words and a unique slang, police were able to determine their list included a particularly high-value target: Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić.

Đinđić had taken charge in 2001, following the collapse of the Milošević regime. His reforms included a plan to introduce special prosecutors and courts to crack down on organized crime.

Investigators also determined that Maksimović wasn’t the gang’s shot-caller. That role was filled by an unidentified senior leader in another country, beyond the reach of their phone surveillance.

Wiretaps show the mobsters favored Serbian President Vojislav Koštunica, an opponent of Đinđić who wanted the more powerful prime minister’s post.

In August 2002, two months after the Buha hit, Maksimović was heard telling a woman in Serbia that he’d been ordered to assassinate Đinđić and other government officials so that Koštunica could move up.

“You see, they told me that all of the shits [politicians] must be ’poplješću’ [killed],’’ he said, using the gang’s odd mix of slang and code words. “It’s over. Oštičava [Koštunica] must come and make another course... Zrika [Đinđić] goes, and most likely he will get it in his head, 100 percent.”

Maksimović said several terrorist actions were needed to put the group in control of illegal activities and make a fortune.

“It must be perušanje [killing],’’ he said in a call. “Without perušanje, nothing will happen.“

Maksimović said that the gang had taken up positions around Koštunica.

“We’re making deals now, we are preparing this plan,’’ he said. “[Koštunica] doesn’t know about it. He is a donkey. We are planting people around him.”

But the planned murder was delayed by a conspirator he didn’t identify.

“We got close to [Đinđić], we have him while he pisses,” Maksimović said. “It’s over ... God cannot save him. It’s just that she was begging me to wait.“

To prepare for the killing, Maksimović brought back to Serbia Nikola Maljković, a gang member who had been moved to Montenegro after the Buha hit.

The police were waiting for him.

“They took our girl,” Maksimović said on a later call, using gang code that switches the gender of the subject. “I didn’t expect it, and gave the green light to go there, and she goes, and so.“

Intelligence Involvement

Maljković and four other Group America associates were arrested in late October 2002. Maksimović remained in Montenegro, beyond the reach of Serbian police.

Those arrests provided disturbing additional evidence that the assassins had friends in the shadows.

A raid on the home of gang associate Dragan “Limar” Ilić turned up a cache of weapons, including two guns owned by the Serbian intelligence service (now called BIA). Ilić also had passed a BIA-owned automatic weapon to Buha’s alleged assassin.

Two BIA officials who had access to the weapons were later prosecuted. The Group America associates were all charged with terrorism.

In announcing the raids and arrests, Đinđić said the need to preserve his government — and to prevent his own murder — outweighed calls for a longer investigation to find all of the conspirators.

“Perhaps a part of the criminal network remains hidden, but I think that the consequences of another outcome, especially as far as I am concerned, would be negative," Đinđić said.

The prosecutor in the case said Buha had been chosen at random from a list of prominent people with law enforcement ties who would be easy targets.

Maksimović was tried in absentia. The case against him and his alleged conspirators didn't go smoothly.

While under suspicion but not yet indicted, Ilić was kidnapped and brutally tortured by the rival Zemun Clan, which wanted to damage Group America by getting him to provide evidence that Maksimović had ordered Buha’s murder. Ilić later identified his attackers in court but the charges against them were eventually dismissed.

Đinđić fell victim to another assassination plot a few months later. In March 2003, the prime minister was killed by the Zemun Clan, which wanted to head off a police operation he was organizing. That gang was dismantled through a police action known as Operation Sablja (“Saber”) in the months after the assassination. Two of the gang’s leaders were killed by police and a third was sentenced to the maximum 40 years in prison.

In the end, Group America got what it wanted. Koštunica became prime minister in 2004 with the support of the Socialist Party of Serbia. His associates took control of police and other pillars of government power.

The terrrorism case against Maksimović and his associates melted away.

Judges said they couldn’t be certain the voices recorded in the wiretaps were really those of the accused because the alleged assassins declined to speak in court for comparison. They also dismissed other evidence, including testimony from witnesses who said they recognized the voices.

All of the accused walked free in November 2004.

Prosecutors appealed the wiretap rulings, and in late 2005 a new trial was ordered.

By that time, the suspects had disappeared.

Though back on the street, the Group America associates still had to deal with the harsh realities of their profession.

Slobodan Resimić, an associate of Maksimović and a friend of Maljković, had agreed to cooperate with police and testified that Maljković told him that he had killed Buha and needed to flee to Montenegro.

After the Buha hit, police wiretaps picked up members of Maksimović’s group discussing the need to eliminate someone who knew too much.

“If little rabbit is standing on the meadow, and then you bring a jackal, the little rabbit will not stand there anymore, is that right?” a member of Maksimović’s group said.

Resimić later testified in the Buha case that assassins came to his house but he was able to escape in a car and get protection from Zemun Clan leader Dušan Spasojević.

Spasojevic saved Resimić, but judges dismissed his testimony, saying it might have been influenced by the Zemun Clan to incriminate Group America.

The Hunters Become Prey

Police officials who had investigated the Buha murder also suffered following the change in government.

Milan Obradović, the Belgrade Police head who organized the investigation, was himself arrested and accused of participation in Ilić’s torture. He was jailed for two months before charges were dropped.

Now a pensioner, Obradović declined to comment on the case, saying only that his “head is in the bag,” meaning that he remains in great danger.

Obradović was targeted by the Interior Ministry’s inspector general’s office, a police organization then led by Vladimir Bozović, who became Serbia’s ambassador to Montenegro in 2019.

Obradović in 2005 told the investigative TV show Insajder that Bozović knew in advance that Maksimović wouldn’t be convicted.

“Mr. Bozović told me... that [Maksimović] would be acquitted, and he had told me that a month or month and a half before the judgment was released. Which, for me, is a bit of a strange circumstance,’’ Obradović said. “He told me that they would be released, and that I would be guilty. It is unclear to me how he could know it a month before?”

Bozović had also worked with the lawyer of one of the defendants, Obradović said, describing this as “a conflict of interest.”

In 2011, Bozović was seen in Uzice, paying his respects at the funeral of Boško “The Yugo” Radonjić, the founder of Group America.