The report, which UNODC developed according to data provided by partner organizations under the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime, highlights that wildlife crime is not limited to a specific region, but that it is a global phenomenon, with all the world’s regions playing the role of either source, transit, or destination for contraband wildlife. Traffickers of about 80 nationalities have been identified.

The UNODC report heavily relies on the global seizure database “World WISE”, which, while still being a work in progress, already contains 164,000 seizures from 120 countries. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the World Customs Organization contributed to this data.

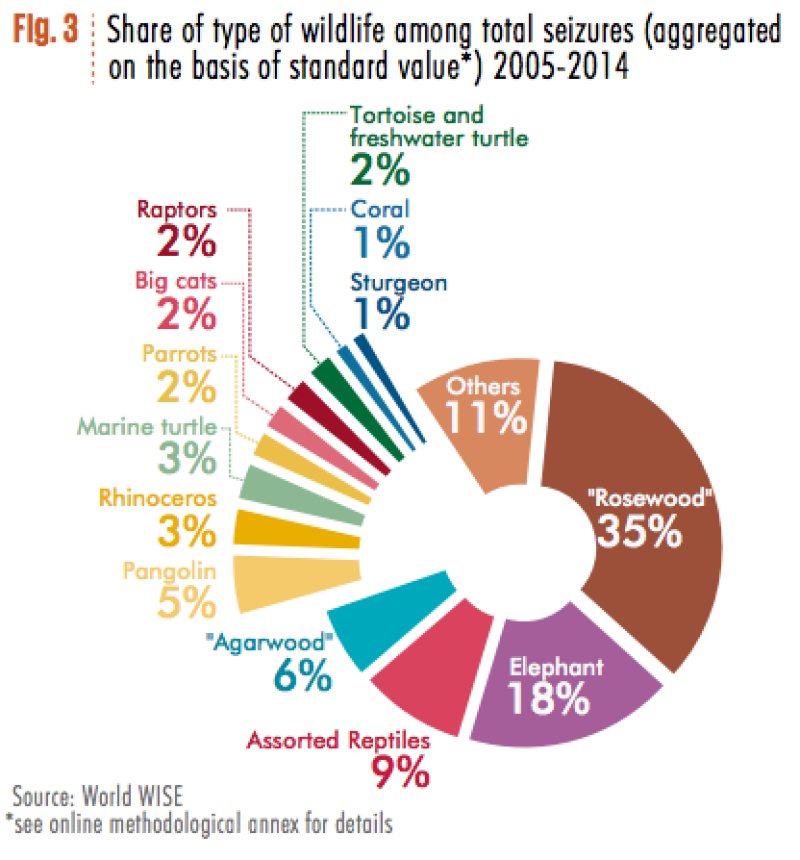

Relying mainly on information from CITES, the report identifies nearly 7,000 species that have been seized, including reptiles, mammals, corals, birds, fish and others.

Not one of those species constitutes more than six percent of all seizure incidents.

While wildlife trafficking operations are globally occurring, certain species are strongly associated with each region.

Trafficking birds is strongly associated with Central and South America, mammals with Africa and Asia, reptiles with Europe and North America and corals with Oceania.

Since the scale, value and impact of wildlife trafficking operations is very diverse and thus difficult to compare, the research process in creating the report takes into account many aspects in order to provide a general overview of global wildlife trafficking. An example, as stated in the report, is the trafficking of tiger skins. The World WISE data identifies 380 tiger skin seizures between 2005 and 2014, worth a mere US $4 million. However, since there are only about 3,000 tigers left in the wild, the ecological impact of these seizures is much bigger than the monetary value of the illicit operation.

Wildlife crime groups are usually concentrated on smuggling one particular species. However, there are exceptions, as, for example, ivory, rhino horn and pangolin scales have been seized in the same shipment multiple times.

The report also finds that the relationship between the legal and illegal markets regarding wildlife products varies based on the products.

Research shows the legal market for ivory is much smaller than the figures showing the illicit supply of “hundreds of tons” of it annually, indicating that most of the illicitly acquired ivory ends up in an illegal market, and that only a small part of the illicit ivory is being sold through the legal market. The same can be said about the trade in Asian pangolin – between 2007 and 2013, 1,467 of them were traded legally, yet 107,060 were seized as contraband. The market for rhino horns is exclusively illegal, as there is no legal market for the product.

On the other hand, products with vast global markets, such as wood and seafood, are often acquired illegally, yet sold in a legal market – the buyers often have no idea about the illegal origin of the product. This may be the case if there is no international regulation regarding a species, or if the traffickers forge or in any way fraudulently acquire the relevant paperwork.

According to UNODC General Director Yury Fedotov, “...criminals exploit gaps in legislation, law enforcement and criminal justice systems.”

However, the report emphasizes it does not cover all aspects of wildlife crime. Since it heavily relies on CITES, which tracks the trade of 35,000 protected species, the data does not account for the many wildlife crimes affecting species that are not among those listed by CITES. The data is also limited to international trade, so the report does not account for poaching of protected species or domestic markets for illicit wildlife products.