OCCRP spoke with cybersecurity experts and a source privy to the ongoing negotiations, coordinated by the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, on an envisioned convention for countering use of ICT technologies for criminal purposes.

They suggested Moscow has styled itself an “honest broker” on cybersecurity issues to win support from developing countries, pushing for provisions that would further enable suppression of dissent at home and widen the way for cybercriminal groups to pursue attacks against unfriendly states.

“From the beginning it’s been highly politicized,” an official with knowledge of the process told OCCRP. “It’s been extremely sensitive, and deep down I think it’s an issue of trust between countries, which includes trust towards Russia and Russia trusting other countries.”

The Permanent Representative of Russia to the United Nations did not respond to requests for comment on the negotiations.

Russia has been keenly interested in how cyberspace is governed since the late 90s, amid historic concerns over what was believed to be the West’s competitive advantages in this area, and was in fact the member state to submit the initial proposal for the treaty.

Russian official Andrey Krutskikh and academic Anatoly Streltsov argued in a 2014 article that the Council of Europe’s existing Budapest Convention on Cybercrime, which Russia declined to sign, violates principles of state sovereignty by permitting cross-border investigations into crimes committed in cyberspace.

Though Russia’s resolution establishing the committee to draft the U.N. convention passed in December 2019, it was without a majority of states in favor, which the official told OCCRP spoke to the lack of trust that has characterized negotiations so far.

Since then, Moscow has been eager to drum up support for criminalizing ‘content-related conduct’, in particular regarding online extremism and terrorism, which it has received from a small coalition of countries including China, Tajikistan, India, Burundi and Nicaragua.

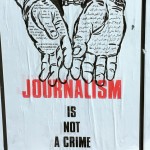

Commentators have raised concerns that provisions of this sort would empower states to prosecute legitimate opposition by deeming such actors a threat to security.

“Terrorism is a huge issue for many countries. But if you put a provision like this in the convention, it raises the question of how it will then be used and interpreted by states, and it could potentially be used as a loophole for doing other things,” the official explained.

Valentin Weber, a cyber research fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations, says this should not be taken lightly given Russia’s ongoing suppression of free expression and persecution of dissent, which has only worsened since the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

“Their optimum outcome would be the adoption of a binding treaty that enumerates content-related cybercrimes, which could then be used to infringe on freedom of expression or assembly,” he told OCCRP.

Earlier in March, Russian lawmakers voted to drastically toughen the country’s laws on fake news. Those who knowingly disseminate ‘false information’ about state bodies operating abroad, including the military, can now face fines of up to 1.5 million rubles (US$28,000), and a prison sentence of up to 15 years.

Many have decried the move as a widening of the state censorship apparatus -- and Weber observes that the language used in the recent legislative changes is notably similar to Russia’s proposals for provisions against content-related conduct for the U.N. treaty.

“It’s almost word for word the same as the ‘fake news law’,” he said. “So you have material based on political, ideological, national enmity that’s being criminalized at home, and Russia also wants to criminalize that at the international level.”

There’s a certain irony in Russia pushing for robust provisions against criminal activity in cyberspace, given evidence to suggest Moscow’s preparedness to utilize, or at the very least give free rein to, the country’s immense market for cybercriminal services.

“Russia has reached a tacit agreement with cybercriminal groups in its territory, which translates into them being able to attack any computer system that isn’t based in the country,” Weber said.

“In addition, it is believed that some of these criminal operations, which have caused billions in damages, are also used by Russia to gather intelligence abroad,” he added.

Alongside provisions against content-related conduct, Moscow has been eager for protections around sovereignty. This might mean states signed up to the treaty could not be forced into turning over any data they collect on criminal activity, potentially enabling Russia to provide cover for cybercriminal networks operating within its borders who attack targets abroad.

“So you’d always have plausible deniability. You could claim you are not able to investigate or that you haven’t found anything, because the provisions on sovereignty would cover you,” Weber says.

Gavin Wilde, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, similarly argues Moscow wants to “have its cake and eat it too” in respect of its position in the ongoing negotiations.

“There’s an old quote that “the law is designed to permit some and constrain others,” and I think that goes double for Russia’s interests in this,” he said.

“They’re looking to simultaneously find ways to enable some of the behavior that’s emanating from within their borders and create deniability, while curtailing other activities,” he added.

However, the official who’s been present for talks on the treaty says there remains room for optimism.

The committee’s first organizational session took place in February on the very same day Russian troops moved into Ukraine, and the invasion has apparently since galvanized opposition to some of the country’s more troubling proposals.

Vladimir Putin has described Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine as a process of “denazification,” playing to conspiracy theories espoused by state media that the Ukrainian government has been compromised by neo-facist elements since the 2014 revolution.

“When it came to Russia proposing a provision on online extremism, specifically its provision on ‘rehabilitating nazism’ online, a number of countries strongly opposed it,” the official said.

“They said well, we’ve seen this kind of rhetoric in respect of what’s going on with the war. Their ideal would be to use this provision against Ukraine, and it is not something we can support,” they added.

As tensions continue to mount between Moscow and Washington over the conflict, Krutskikh recently told Newsweek that Russia remained eager for progress on talks to secure more effective governance of cyberspace.

“Regardless of geopolitics, Russia remains open for dialogue and cooperation on information security with all states,” he said.