Since 2008, the global oil company BP (formerly British Petroleum) had run into a series of problems in its Russian business. A once-promising partnership degenerated into police raids and bitter, protracted courtroom battles.

Yet in 2013, BP experienced a change of fortune, finally succeeding in unloading its shares in TNK-BP (Tyumenskaya Neftyanaya Kompaniya-BP), its troubled joint venture with a Russian consortium, to Rosneft. In the multibillion-dollar deal, BP received a 19.75 percent stake in Rosneft in addition to the cash. TNK-BP was at that time among the top 10 privately owned oil firms in the world, according to a 2011 company report.

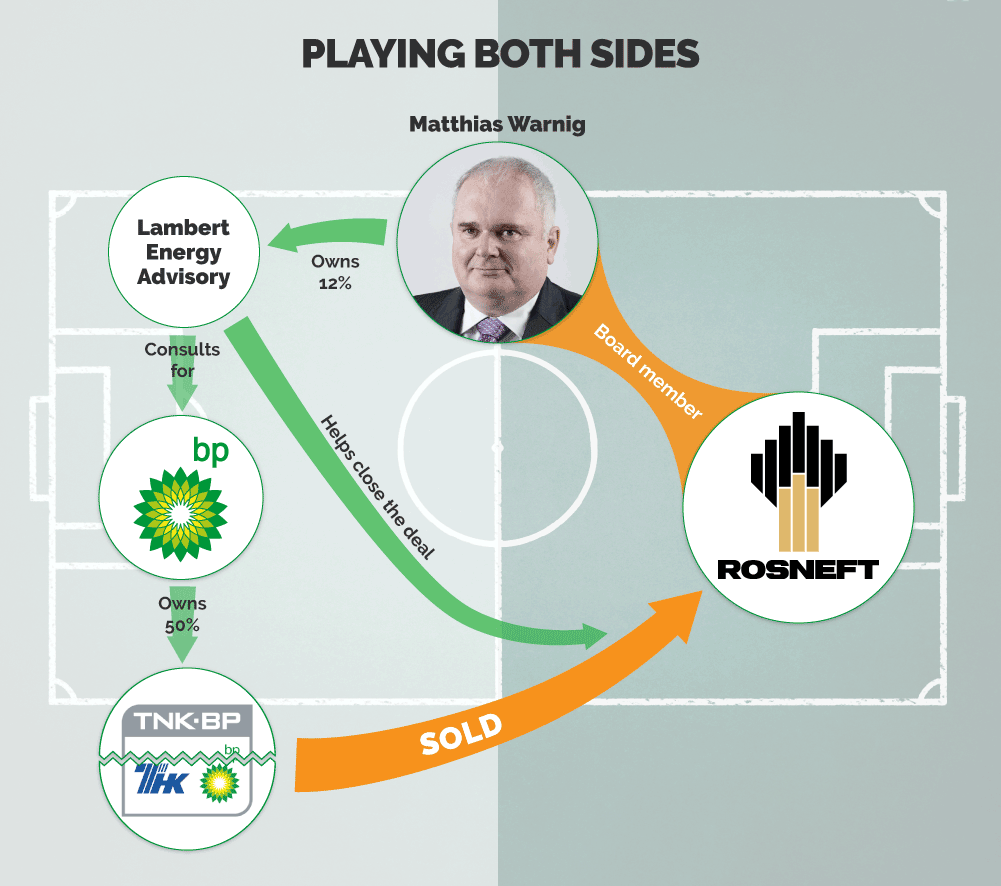

In the end, a key personal connection may have made the sale possible.

BP had hired the London-based Lambert Energy Advisory as a financial consultant to help it close the TNK-BP sale. As it turns out, over twelve percent of Lambert belongs to an old friend of Putin’s, a former East German intelligence agent named Matthias Warnig.

Warnig has other high-profile connections. He serves on the Rosneft board and shares business interests with former Russian Minister of Energy Sergei Shmatko.

“He can open the door to Vladimir Putin's office,” said a former high-ranking Russian official who knows both Warnig and Putin. “Putin trusts him.”

Warnig’s spokesperson, Irina Vasilieva, denied any wrongdoing.

Cold War Pals

Matthias Warnig. (Photo: Nord Stream AG) Warnig, 61, was once an agent of the foreign intelligence service of the Stasi, the feared secret service of former East Germany. Today he is one of a select group of foreigners welcomed in the world of Russia's large state-owned companies.

Matthias Warnig. (Photo: Nord Stream AG) Warnig, 61, was once an agent of the foreign intelligence service of the Stasi, the feared secret service of former East Germany. Today he is one of a select group of foreigners welcomed in the world of Russia's large state-owned companies.

In addition to serving on the Rosneft board, he is a board member of Transneft, the state-owned oil pipeline company, and the chief executive officer of Nord Stream 2 AG, the consortium that builds and manages Russia’s new gas pipeline to Western Europe.

Warnig most likely first met Putin in Dresden, where Putin was posted from 1985 to 1990 by the Soviet KGB, a close ally of the East German secret police.

“Matthias Warnig was an officer of the [Stasi],” says a former KGB officer who knows both men, speaking on condition of anonymity for fear of retribution. “He was one of those who maintained relations with KGB operatives.” At that time, in the 1980s, there were six operatives from the KGB in Dresden, including Vladimir Putin, he added.

Irina Vasilieva, a spokeswoman for Nord Stream 2 who answered reporters’ questions on Warnig’s behalf, said he didn’t meet Putin until the fall of 1991, when he opened a bank branch in St. Petersburg.

The biographies posted on websites of the Russian companies Warnig is involved with don’t mention his Stasi past. But in 2005, the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta published Warnig's official Stasi registration card, which showed that he began working for the agency in 1975 and that, a month before the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, he was awarded a gold medal “for faithful service.”

In 1991, Putin was appointed to lead the international relations committee of the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, where one of his main tasks was to attract foreign investment to the city. Warnig was among the first wave of Western bankers in 1991 when he opened the St. Petersburg subsidiary of BNP-Dresdner Bank.

The two men’s relationship soon developed into a real friendship.

“Putin is a grateful man, and he is attached to the people he has known for a long time,” the Russian ex-official explained. Putin particularly remembers people who have supported him, he said, such as in 1993, when his then-wife Lyudmila needed medical treatment after a serious car accident. Warnig and Dresdner Bank assisted in providing her with rehabilitation treatment in Germany. “The president of Russia does not forget such things,” the former official said.

Indeed, Warnig’s business career got a major boost a few years after Putin became president in 2000. He joined the boards of some of Russia’s most important state-owned companies.

“Everyone understands that [Warnig] can walk into the office of Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin], that he’s trusted by him and that he advises him on important questions. In other words, if [Warnig] says something, one should pay attention, because [he] might be carrying out delicate orders,” said the former high-ranking Russian official who knows him.

In 2002, Warnig became the president of Dresdner Bank in Russia. A year later, in 2003, he joined the board of Rossiya Bank, a St. Petersburg institution that’s known as the bank of Putin's friends.

BP’s long and difficult history in Russia

The company formerly known as British Petroleum is one of the world’s mightiest oil companies, with operations in more than 70 countries. But for many years, BP’s business in Russia -- a key oil superpower -- was beset with problems.

Its partnership with a consortium of Russian investors, established in 2003, later sank into bitter acrimony, leading to fierce legal wrangling and even police raids.

The Alfa-Access-Renova (AAR) consortium, BP’s Russian partner in the TNK-BP joint venture, consisted of four powerful oligarchs: Mikhail Fridman, German Khan, Leonard Blavatnik, and Viktor Vekselberg. Shares in the venture were split 50-50 between BP and AAR.

Relations between BP and AAR deteriorated in 2008, descending to the use of pressure tactics typical in Russia, such as raids by law enforcement and redundant checks by tax authorities. Russian shareholders demanded the resignation of TNK-BP President Robert Dudley, on the grounds that BP was running the company as its own subsidiary, rather than for the benefit of all shareholders.

In the end, Dudley was forced to leave Russia because he could not get a work visa. He continued to run the company from abroad. "The company and I have faced unprecedented investigations, proceedings, enquiries, and other burdens," said Dudley, according to a personal statement cited by The Telegraph.

In 2011, relations between BP and AAR deteriorated further after BP started direct negotiations with Rosneft to jointly explore a new field on the Arctic shelf. Concerned they would miss out on a lucrative deal, the Russian shareholders successfully sued to stop it in the Stockholm Arbitration Court, which decided that, by negotiating directly with Rosneft, BP had violated TNK-BP’s shareholder agreement.

It looked like BP was in trouble. “BP Needs Friends in Russia,” read the headline in the Wall Street Journal. The firm was looking for a way out.

Finally, in 2012, BP announced that it had received “unsolicited indications of interest” to buy its 50 percent stake in TNK-BP, according to the Financial Times. The Wall Street Journal and the Russian business press quickly reported that the offer must have come from Rosneft, the state oil giantг. In a Wall Street Journal interview, AAR co-owner Fridman dismissed the possibility. “We doubt [BP’s statement] has any basis in fact,” he said. “Our understanding is that among Russian companies, not one has conducted any serious negotiations with BP and no one intends to," Fridman continued. "Our view is that there are no serious buyers.”

Nor did some powerful figures within the Russian government back the possible deal. "I don't even want to think about it. Perhaps there are some thoughts inside some of these companies, but we do not support them," First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov told the Wall Street Journal.

But then something changed. What had seemed untenable -- the biggest deal up to that time in Russia's energy market, and one seemingly opposed by some of the country’s most powerful figures -- in fact took place.

On March 20, 2013, BP sold its 50 percent share in TNK-BP to Rosneft. The deal was done.

On March 21, 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with the heads of Rosneft and BP to mark the completion of Rosneft's acquisition of TNK-BP. (Photo: Kremlin.ru)

On March 21, 2013, Russian President Vladimir Putin meets with the heads of Rosneft and BP to mark the completion of Rosneft's acquisition of TNK-BP. (Photo: Kremlin.ru)

On the next day, Rosneft announced that it had also purchased the other half of TNK-BP -- the shares that had belonged to AAR -- leaving it with control of the entire company. As one of the Russian shareholders involved told OCCRP, AAR had decided that they did not want to be left with the state-owned giant, Rosneft, and its powerful chairman, Igor Sechin, as a business partner.

Help from London

Click to enlargeBP used the services of Lambert Energy Advisory, the British financial consultancy, to help it close the Rosneft deal.

Click to enlargeBP used the services of Lambert Energy Advisory, the British financial consultancy, to help it close the Rosneft deal.

How much Lambert earned for its services is unknown, as neither party disclosed the sum. Spokespeople for BP would not say if the company knew that Warnig, the former Stasi agent and friend of Putin, owned Lambert Energy shares.

Warnig became a shareholder in the company in 2008. He continues to hold over 12 percent of Lambert through his Swiss company, Interatis AG. Lambert’s headquarters is located at Hill Street in the posh central London district of Mayfair, about 300 meters from Hyde Park. The company was established by Philip Lambert, whose family now controls the company, and Lord James Rockley, a British aristocrat who died in late 2011.

Lambert Energy Advisory doesn't appear to seek publicity -- it doesn't even have a website. But Warnig is not its only well-known shareholder. Tore Sandvold, the former director general of Norway’s Ministry of Oil and Energy, and Sir Jeremy Greenstock, a retired British diplomat and former special advisor to BP, are company directors. Sandvold Energy, of which Sandvold is chairman, and Anne Greenstock, presumably Greenstock’s wife, also hold minority stakes in the firm.

The company holds its German investor in high regard. “Since December 2008, Matthias Warnig has been an exemplary, trusted and long-term shareholder in Lambert Energy Advisory Ltd,” wrote Philip Lambert to OCCRP.

Strict standards of confidentiality

Neither Lambert Energy nor BP would comment on why Warnig's company was chosen as a financial consultant or whether the personal involvement of Putin's long-time friend helped make the TNK-BP deal possible.

But Warnig’s role in the deal raises questions among anticorruption experts. He was on the board of directors of Rosneft when it approved the decision to buy the stake in TNK-BP; Rosneft didn’t respond to reporters’ questions about whether the deal represented a conflict of interest.

In addition, Warnig’s long-time acquaintance Sergei Shmatko, who resigned from the Russian Ministry of Energy later that year, was one of the few top Russian officials to publicly support the BP-Rosneft deal. He was Minister of Energy until May 2012, a few months before the deal was agreed. Irina Vasilieva, Warnig’s spokeswoman, confirmed that the two had known each other since the mid 1990s.

The Rosneft deal was concluded in 2013. The following year, Shmatko’s Moscow-based company, Artpol Holding, and Warnig's Swiss company, Interatis, both invested on the same day in two Russian companies, the anti-cancer drug producer Refnot-Farm and anti-bacterial drug producer Firma Ferment.

Anton Pominov, the executive director of Transparency International-Russia, says this web of connections raises a number of questions. As a Rosneft board member, he notes, Warnig approved the deal between Rosneft and BP while holding shares in Lambert, the financial company advising BP on the deal. And soon thereafter, he made a simultaneous investment with ex-energy minister Shmatko, who had publicly supported the BP deal.

Warnig’s spokeswoman Vasilieva, however, said Warnig's “involvement in Lambert Energy is limited exclusively by his role as a minority shareholder. He doesn't hold any management or supervisory positions in the company. His financial benefit consists solely in the receipt of dividends,” she said.

“Mr. Warnig attaches high importance to the conscientious conduct of business in accordance with the standards of corporate governance and avoidance of conflict of interest. This also applies to his minor participation in Lambert Energy Advisory.”

Phillip Lambert cited client confidentiality and business ethics in declining to answer reporters’ questions. “We are neither willing nor able to discuss your specific questions,” he wrote, stressing that his company has “rigorous compliance procedures.”

BP's spokesperson confirmed that Lambert Energy advised BP in the deal with Rosneft, but also cited confidentiality in declining to comment further.

Rosneft provided no comment.

Financial experts find it difficult to estimate how much Lambert Energy may have been paid for its work on the deal. "[The fee] might have been very expensive for consulting. Usually the uniqueness of advisers and their potential ability to influence the situation has, of course, a direct impact on the size of the sum that may have to be paid," says Alexander Zakharov of Paragon Adviсe Group, a financial consultancy.

There are certain questions that need to be answered by BP as well, says Pominov: “While facing troubles in Russia, BP hired the company of a politically exposed person close to the Russian president. Was it the way to get person from Putin's surrounding to solve problems in Russia?”

Ilya Shumanov, deputy director of TI-Russia, collaborated with OCCRP on this story.

This story is part of the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, a collaboration started by OCCRP and Transparency International. For more information, click here.