Two alleged smuggling schemes run through the Brazilian border town of Pacaraima give a glimpse into the murky world of Venezuela’s illegal gold trade.

How Venezuelan Gold is Trafficked Through Brazil’s Borderlands to the US

Published: 26 May 2023

The landscape of Roraima, on the border with Venezuela in northern Brazil. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

By Joseph Poliszuk (Armando.info), María de los Ángeles Ramírez (Armando.info), Eduardo Goulart (OCCRP)

Pacaraima, on the northern edge of Brazil, is a town shaped by migration. Every week, scores of people cross the border from Venezuela to escape an economic and political crisis that has plunged millions into abject poverty.

It has also become known as a hotbed for gold trafficking.

In recent years, Brazilian police have busted two alleged smuggling schemes that they say funneled millions of dollars’ worth of Venezuelan gold across the border into Pacaraima, and from there out of South America to the U.S., Asia, and the Middle East.

One was allegedly run by Andrés Antonio Fernández Soto, a convicted gold smuggler from Venezuela, who police say used companies owned by him and his family to traffic gold to Miami. Police detained Fernández — who goes by the name “Toñito” — after he was caught trying to move gold mined from protected land in the Venezuelan Amazon through Brazil.

The other case focuses on a group that allegedly smuggled Venezuelan gold across the border to buy food, medicine, and other basic goods in Pacaraima. Brazilian police say the gold was sold to a major metals trader in São Paulo, which exported it to India and the United Arab Emirates. Some of the gold, they suggest, may have come from Toñito and his family.

The Brazilian and Venezuelan flags mark the border between the two countries. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

The Brazilian and Venezuelan flags mark the border between the two countries. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

Brazilian authorities are now searching for Toñito, after he removed a monitoring device from his ankle late in March and went on the run. Neither Toñito, nor any members of his family, replied to a request for comment.

The two cases give a rare glimpse into the murky world of Venezuela’s illicit gold trade. Experts estimate as much as 75 tons may be extracted from the country’s mines every year, worth more than $4.8 billion at today’s rates. Most of it is thought to come from illegal mines, where workers toil in often horrendous conditions.

Official figures are unreliable, however, and the opaque ecosystem of criminality surrounding the trade make it impossible to quantify. Based on accounts from miners and local officials, experts say Venezuela’s illegal gold industry is growing, driven by the same economic devastation that has led so many people to flee the country.

“In this context, gold [has become] the new oil,” said a 2021 report from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “Most of Venezuela’s gold continues to be smuggled abroad, laundered and eventually sold to traders and refiners around the world.”

In Pacaraima, the cost of Venezuela’s crisis is plain to see. Groups of migrants, some clutching infants in their arms or carrying bulging rucksacks, crowded the sidewalks when Armando.Info visited last year.

A group of Venezuelan migrants in the Brazilian border town of Pacaraima. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

A group of Venezuelan migrants in the Brazilian border town of Pacaraima. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

As the trade has grown, smugglers have come up with new ways to disguise the origin of Venezuelan gold. The two cases show these different techniques, from trying to pass it off as scrap to routing it through neighboring countries, such as Brazil.

Until recently, Brazil’s laws made “heating gold” — as laundering is sometimes known in Portuguese — relatively easy. A “presumption of good faith” rule meant that anyone could sell gold without proving it had been legally extracted, just by attesting that it had.

"If you go to a point of sale here in Brazil and say, 'Look, I extracted this gold,’ and you provide the process number of an authorized mining operation, simply because you can say it in good faith, you can easily legalize that gold,” said Melina Risso, the research director at Instituto Igarapé, a sustainability think tank based in Rio de Janeiro.

In April, the Brazilian Supreme Court suspended the presumption of good faith of gold-buying companies, but the ruling is a preliminary decision and could still be overturned.

‘A True Criminal Organization’

For a while, Pacaraima was a safe haven for Toñito. Police say he made millions from trafficking illegal gold into Brazil before he was detained there in 2021.

Toñito had slipped across the border three years earlier, after he was convicted in Venezuela for smuggling 100 kilograms of gold, worth some $6 million. When he fled to Brazil, Interpol issued a red alert seeking his arrest.

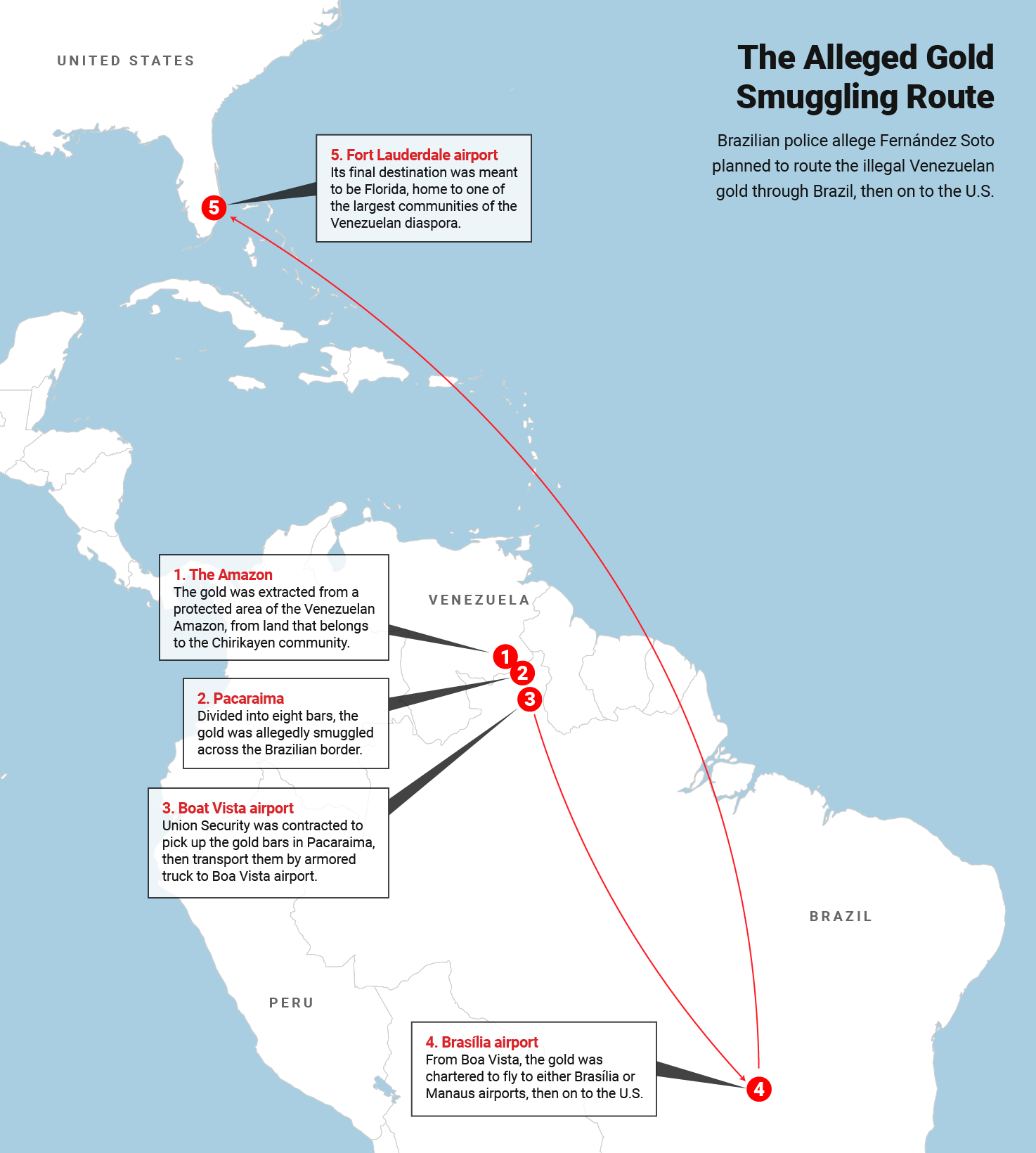

Previously, Toñito had flown illegally mined gold from the Venezuelan Amazon directly to the U.S. But when Washington banned Venezuelan imports in 2018, investigators say he and his family rerouted their trade through Brazil to disguise the gold’s origins.

(Infographic: Edin Pasovic/OCCRP)

(Infographic: Edin Pasovic/OCCRP)

Once in Brazil, Toñito applied for asylum as a refugee — and allegedly set to work trying to smuggle gold out of Venezuela again. But Brazilian police were alerted after they caught a trader carrying around $46,000 in cash, who told them that he was planning to buy gold from Toñito’s brother in law.

The discovery prompted police to launch an investigation into Toñito and his group, codenamed Operation Chain. While the investigation is still ongoing, some of their findings are laid out in documents submitted to court so police could detain Toñito in 2021.

A judge who reviewed the papers described Toñito’s enterprise as “a true criminal organization, with a well-defined hierarchical and compartmentalized structure, which moved large amounts of money related to gold extracted from indigenous lands — and probably other crimes.”

The table-topped mountain which overlooks the indigenous village of Chiricayen. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

The table-topped mountain which overlooks the indigenous village of Chiricayen. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

The documents give an unusually detailed insight into how illegal supplies make their way from the Venezuelan Amazon into the international market.

The investigation focuses on one shipment of eight gold bars extracted in Gran Sabana, a group of protected indigenous territories in the south of the country where mining is supposed to be banned. In the village of Chirikayén, not far from the mine, small rows of thatched houses lined neatly manicured dirt tracks, overlooked by the summit of a flat-topped mountain known to locals as the “reclining Indian.”

The mine was a hive of activity when Armando.Info visited earlier this year. Trucks came and went carrying sacks of gold. Day and night, aircraft would appear loaded with rock material, landing on a nearby helipad or, sometimes, the local community's soccer field.

The gold bars mined here were bought by a Venezuelan company owned by Toñito’s sister in January 2020, then sold to a Florida-registered company controlled by Toñito and his mother five days later, according to sales records. Police say the bars were then smuggled across the border from Venezuela to Brazil, though they don’t explain how.

Once in Pacaraima, the bars were handed to Union Security, a private security company that was meant to drive the gold in armored trucks to the airport in the state capital, Boa Vista.

There, the bars were to be entrusted to a charter airline that would fly them to Florida. Paperwork shows a flight had already been booked to transport the gold to Fort Lauderdale on February 12, at a cost of nearly $30,000.

But there was a hitch.

To export the gold from Brazil, Union Security needed to be approved as an international transport carrier. Brazilian authorities were on high alert when it came to gold shipments after armed groups had stolen cargoes from other airports.

The paperwork for the gold bars was also problematic, including an old U.S. customs certificate that authorities said was intended to “mislead” customs officials. It also claimed the gold would be transported by Toñito’s own plane, rather than the one he had chartered.

Unimpressed by Union Security’s application, Brazil’s Federal Revenue Service turned it down, noting in its decision that there was a "high risk to public safety due to the nature of the cargo." Toñito, Tremens Metals, and Union Security filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the decision, but they lost the case.

The Brinks Company, which bought Union Security in 2021, said it was not "informed” that Tremens Metals had contracted Union Security to transport gold in its due diligence for the acquisition. Brinks said it had a rigorous governance policy when it came to moving precious metals.

A truck reporters spotted in Gran Sabana close to the Venezuelan border with Brazil. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

A truck reporters spotted in Gran Sabana close to the Venezuelan border with Brazil. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

Brazilian police detained Toñito in October 2021, but he escaped house arrest and is now on the lam. The justice department in the state of Roraima, where Pacaraima is located, said intelligence agents are searching for him.

Toñito’s two sisters and brother in law, who were arrested at the same time, are also awaiting trial. Brazilian police declined to comment as the case is ongoing.

But this wasn’t the only trafficking case implicating Toñito and his family. Brazilian police also have evidence they supplied another group that smuggled illicit gold across the border to buy food and medicine.

Food for Gold

The second alleged smuggling scheme uncovered in Pacaraima took advantage of the widespread shortages of basic goods that have driven millions of people to flee Venezuela.

At least 19 people are under investigation for being part of a criminal group that smuggled Venezuelan gold into Brazil to buy food and medicine that was unavailable across the border. Brazilian police raided several properties in March in connection with the alleged scheme, which they estimate laundered 40 million Brazilian reais ($8 million).

The ringleader, police say, was a Brazilian named Marcelo Camacho Pinto. In messages cited in investigative documents he describes how he acted as a middleman between the gold smugglers and shops in Pacaraima.

"The Venezuelans give me the [gold] and they sign a certificate of origin. With this material … I make the payment to the companies that sell the food,” Camacho said in one message to his lawyer.

In an audio message also cited in the file, Camacho explained he would also buy the gold himself. "Sometimes, there are situations where I pay in cash and other situations I also pay the supermarkets where they buy the food," it said.

OCCRP could not read Camacho for comment.

The Goiana supermarket in Boa Vista, a Brazilian border city. This and other establishments received deposits from companies that then traded Venezuelan gold for food. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

The Goiana supermarket in Boa Vista, a Brazilian border city. This and other establishments received deposits from companies that then traded Venezuelan gold for food. (Photo: María de los Ángeles Ramírez)

Police believe Camacho bought some of the gold from Toñito and his family, though none of them are official suspects.

Bank records show a company owned by his sister Lilia and her husband Sousa & Fernandez Representações received $213,000 from Camacho’s company, MC Produtos de Extração Mineral. The payments, they say, “strongly indicate” Toñito and his family supplied the smugglers with gold.

When officers visited Sousa & Fernandez’s address in the Brazilian city of Boa Vista, it appeared to be little more than a front company. Inside the office was empty, while outside hung a “for rent” sign.

Police say MC Produtos de Extração issued false receipts claiming the gold came from jewelry pawned by Venezuelan migrants in a bid to hide its illegal origins. However, tests carried out by the police on the supposed scrap metal showed it was far more pure than gold used in necklaces or earrings.

The smuggled gold was then allegedly sold to RBM Recuperadora de Metais, a major metals trader based in São Paulo. Between January 2015 and September 2019, police say MC Produtos supplied RBM with 1.2 tons of gold, worth close to $30 million, which was then exported abroad to companies in Dubai and India.

Brazilian authorities were first alerted that Camacho was trading in gold early in 2017, when he tried to send a little over a kilogram to RBM through the mail. The shipment was seized by the Federal Revenue Service.

Investigators became more suspicious when they seized another package of gold a few months later sent by Camacho’s daughter, with an invoice in the name of a Venezuelan miner. Camacho then tried to claim back the gold using fake receipts for jewelry.

Police detained Camacho, RBM’s owner at the time, Valdemir de Melo Junior, and more than a dozen other people in relation to the scheme in June 2019. Although the case is ongoing, Melo Junior has been able to renew several mining licenses he holds in the Brazilian Amazon.

RBM denied that it had committed any crimes, saying prosecutors had not brought any charges against the company. “All of the company's actions are guided by the legal provisions governing its operations, as well as by best compliance practices,” said a spokesperson.

The executive director of sustainable development think tank Instituto Escolhas, Sergio Leitão, said the illegal trade in gold implicated buyers as well as suppliers.

"The consequences are serious and pose a reputational dilemma not only for Brazil, which sells this gold, but also for the countries that buy it. In other words, it is a crime that is committed ... both by those who export and those who import,” he said.

This story was investigated and published by Armando.info, OCCRP, El Correo del Caroní and piauí, with follow-up and support from the Pulitzer Center's Rainforest Investigations Network.