A Nice Kind of Trafficking?

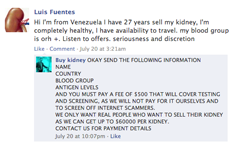

Just as illegal as drug dealing or prostitution, organ trading does not seem to carry the same stigma. But it’s a dirty business that ties the desperately ill and the desperately poor.

Just as illegal as drug dealing or prostitution, organ trading does not seem to carry the same stigma. But it’s a dirty business that ties the desperately ill and the desperately poor.

By OCCRP

The sex and drug trades chase pleasure and recreational highs, but, just as illegal, the organ trade cloaks itself in compassion.

Traders supply organs to those who can’t get them elsewhere. One person gives another additional years of life, and for his sacrifice is financially compensated.

The trade is understood to leave all parties better off.

“The real problem with these markets is they exploit poor people and dress it up as choice,” said Arthur Caplan, head of the Division of Bioethics at New York University’s Langone Medical Center. “The middle class is never going to sell a kidney; they always have other choices.”

Donors are victims of a transaction that leaves them just as poor as when they started out ¬– and medically more vulnerable.

People who sell their kidneys are often desperate, vulnerable and indebted. Selling an organ is a last resort, a selection between suffering financially or physically. A decade ago, reports out of Moldova showed that some 40 people in a poor village of 7,000 had sold a kidney to make ends meet. At the time, Moldova was the poorest country in Europe and it still is.

“People selling an organ live in squalor or abject poverty in which case the notion that they can choose to sell an organ is absurd,” said Caplan. “Choice requires more than a decision to do something. It requires options.”

The illegal organ market is robust because it fills a void. Transplant lists offer no guarantee of an organ. In the US 97,052 people are on the transplant list, waiting an average of three to five years for a kidney, and more than 5,000 die waiting each year. When the healthcare system cannot help them, people look for other options. Those in rich countries look to poor ones to buy an organ that comes with a better guarantee: an additional 10-15 years of life on average.

All about the Benjamin Franklins

Organ sales are facilitated by brokers who fit somewhere between the buyers paying an average of $150,000 for a kidney and the donors likely to get about $5,000.

This potential for fraud, coercion and theft occupies the grey area of the organ trade. “You have middlemen ripping off the sellers and no way to police it or stop it,” said Caplan. ”Sellers have every reason to lie about their health and those operating the market have no incentive to check them out.”

The Declaration of Istanbul on Organ Trafficking and Transplant Tourism, drafted by ethicists, scientists and officials representing 78 countries, was published in July 2008 as an effort to unite those combatting unethical practices in organ transplantation. The declaration defined organ trafficking as the obtaining of organs by means of the threat, force, coercion, fraud, or deception using an “abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability” or a third party to have “control over the potential donor, for the purpose of exploitation by the removal of organs for transplantation.”

Often donors receive less than what they were promised and sometimes nothing, as was the recent case in Kosovo. Be it prisoners in China or elsewhere, it’s not unheard of for people to be killed for their organs.

“The motivation is always money,” said Luc Noel, patient safety adviser at the World Health Organization. “If there’s a way to make money, then unscrupulous people will take it.”

The organ trade operates like any market on the basic principles of supply and demand. Tens of thousands are on kidney transplant lists across the globe and more than 850,000 people in the US alone have end-stage renal disease, meaning their kidneys are failing. Kidney failure is treated in one of two ways: an organ transplant or dialysis, which is laborious, unpleasant and expensive. A kidney transplant costs $110,000, compared to the annual $77,500 cost for a patient on dialysis.

The shortage of voluntary offered organs across the globe drives up demand. It is estimated that only 10 percent of need is being met. As a result, the World Health Organization reports that about 10,000 black market operations take place each year.

Law and order and sometimes morality

Iran is the only country with a legal organ trade. There are no waiting lists and no shortage of donors – though donors are predominately poor. According to Caplan, for a regulated kidney market to be worth it for society, it should benefit the sellers in the long run and should generate more organs. Most importantly it must be monitored.

“I am skeptical that this market is enforceable,” said Caplan. “There are no indications that there’s been success in monitoring the sex trade, for example. Local governments either can’t handle it or they are too corrupt.”

Caplan is also concerned that a kidney market would harm the donation of other organs like hearts and lungs, which are fueled by altruism rather than cash, and can only be donated after death.

Israel: The pariah

Israel leverages compassion against economics to get organs from people who have them to people who need them.

The country was once ridiculed for allowing HMO’s to fund transplants their patients received illegally abroad. The media and physicians compelled the government to reassess the morality of laws that allowed this and the Organ Transplantation Law of 2008 resulted.

Israel copes with a severe shortage of organs, both from living donors and the deceased caused by cultural and religious reasons. To harvest organs from a dead body, the standard is brain death. Orthodox Jews, for example, don’t believe in brain death and regard death only as the moment when the heart stops beating, which is problematic for effective organ harvesting.

HMOs essentially “felt bad for the patient because the only other option is to languish on the wait list and suffer through dialysis,” said Asif Efrat, a professor at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya in Israel.

“They wanted to help the patients and it didn’t hurt that the economic considerations also pointed toward funding the transplants,” said Efrat.

The 2008 law was intended to curb illegal international transplants and address the shortage of organs at home. Now, if you sign a donor card in Israel you will receive a higher priority if you need an organ yourself.

Israel might now easily eliminate the organ trade but has chosen not to “Israeli authorities speak in terms of rights. The patient has the right to life, to health. The patients want to regain their health and the sellers are in a terrible economic situation,” said Efrat. “We can condemn what they’re doing but we are not going to prosecute them. We are not going to deny them these rights by blocking the option of getting a transplant abroad.”

Under Israeli law neither buyers nor sellers can be punished, though buying and selling organs is technically illegal. The brokers and HMOs are not immune to punishment, but brokers often plead out if caught or continue their practice under the radar.

This is why the organ trade is tricky. Both the donor and seller are fighting to survive. They’re not addicts chasing a high.

Luc Noel sees a solution that would leave everyone better off. “The possibility is to strive toward self-sufficiency.”

Norway, for example, is almost completely self-sufficient – although in part this is because it has a lower rate of end-stage kidney disease than most other nations.

“It is achievable and those that are saying it is not are not looking at it,” said Noel. He says success requires five things: government commitment, equality of access and burden of donation, education for prevention to minimize the need for organs, education for maximizing donation after death and transparency and professionalism by physicians that inspires confidence in the system.

Socioeconomic differences in the organ trade are eliminated when everyone who needs an organ gets one and when everyone is prepared to give. Poor people are often the donors, but if they need a kidney they wouldn’t be able to afford one in today’s black market.

“If it would be easy to recognize the poor because they have one kidney we would live in a disastrous world,” said Noel.

The system Noel proposes needs an organization to implement and a governments to manage it. It requires increasing cadaver donation, education on donation and preventive care in order to prevent cases from developing into end-stage renal disease in the first place.