Already reeling from years of civil war and corruption, South Sudan’s economy is being shaken again by plummeting petroleum prices, and a line of creditors demanding repayment for years of oil-backed loans that date back to the beginning of the country’s civil war.

South Sudan was one of a handful of African oil-producing nations to sign “prepayment agreements” with international commodity trading firms, which gave governments cash at the time in return for shipments of oil to be delivered later on.

“Such deals were an important source of financing for many oil-rich governments on the continent during a commodity boom that began around 2007,” said David Mihalyi, a senior economist at the Natural Resource Governance Institute.

When oil prices later fell, first in 2015 and 2016, then again this year, countries like Chad and the Republic of Congo needed more oil than they were able to deliver to repay the money they had borrowed.

When South Sudan took its first prepayments in 2013, oil topped $100 a barrel. Within a few years, prices had halved, effectively doubling the amount of oil needed to repay loans that had already been spent. Then, in April this year, oil plunged below $20 a barrel.

In the meantime, creditors have come calling.

Britain’s High Court in June ordered South Sudan to pay commodity trading giant Trafigura $9.7 million within 30 days. Court documents show the government had already paid an additional $36 million towards the debt earlier this year, following legal action after South Sudan failed to deliver six cargoes on time between May 2018 and March 2019.

South Sudan had instead allocated the shipments to other creditors, according to an oil ministry report that has not previously been made public.

As oil prices have fallen, repayments on oil-backed loans are exacerbating an economic crisis in a country that depends on oil for 85 percent of its national budget.

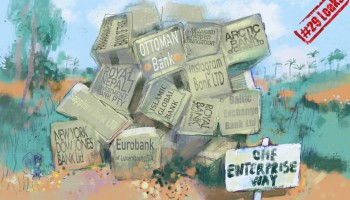

Recipients of South Sudan's oil between June 2018 and May 2019. (Credit: South Sudan Ministry of Petroleum)

Recipients of South Sudan's oil between June 2018 and May 2019. (Credit: South Sudan Ministry of Petroleum)

In August, the Central Bank announced it had entirely run out of foreign currency, sending the South Sudanese pound tumbling and inflation rising. South Sudanese citizens are feeling the pinch as prices of goods and services soar.

“The rate of the dollar in the market makes me wonder how I can survive to feed my family,” said Michael, who works as a driver in the capital, Juba.

“I cannot afford to get medical care for my children because the check-up fee at the hospital is increasing crazily," he said, declining to give his last name for fear of repercussions from South Sudan’s repressive government.

Payments to Trafigura this year alone exceeded the country’s meager healthcare budget of $14 million, and they dwarf the $7.6 million that the World Bank injected to help fight the COVID-19 pandemic.

The servicing of oil-backed loans accounted for about 15 percent of the government’s resources last year, according to budget documents, while falling oil prices squeezed other spending. A Ministry of Finance report shows that by the end of the third quarter, the Ministry of Health had received only 21 percent of its allocated funds. In 2017 and 2018, the repayment of oil advances “left the country without the oil revenue that they’d previously relied upon to finance their budget,” according to a Natural Resource Governance Institute report.

Costly debts have undoubtedly compounded South Sudan’s economic crisis, but the country has been teetering on the brink since gaining independence from Sudan nine years ago, after decades of conflict. Oil was supposed to fuel development in the new nation, but that was undermined by continued violence and corruption.

Then, in 2013, the country spiralled into full-blown civil war.

Tens of thousands of people have been killed and more than a third of its population of approximately 11 million has been displaced within its borders and to neighbouring countries, resulting in Africa’s largest refugee crisis.

Months before civil war broke out, the government started signing prepayment agreements, borrowing more than $300 million over several years since 2013 from Trafigura alone, according to court documents.

Trafigura referred OCCRP to its public disclosure and discussion of prepayments, noting that such arrangements enable “production that would otherwise not be possible – thus underpinning economic growth, job creation and the generation of fiscal revenues,” while providing “producers with unique access to the trading firms’ own banking partners on far keener terms than they could command on their own.”

South Sudanese President Salva Kiir in 2011. (Credit: Al Jazeera/cc-by-sa-2.0)

South Sudanese President Salva Kiir in 2011. (Credit: Al Jazeera/cc-by-sa-2.0)

In addition to being subject to fluctuations in the price and production of oil, experts say prepayment agreements are vulnerable to corruption since their terms are often secret and may include hidden fees.

“Loans from banks and commodity traders tend to be the least transparent and so most open to the resources being wasted or stolen,” said Tim Jones of the Jubilee Debt Campaign, a UK-based advocacy group.

One such secretive deal is revealed in a document from the Technical Loans Committee, which is under the office of President Salva Kiir.

An August 2018 directive obtained by OCCRP ordered the Ministry of Finance to pay an “arrangers fee” of $15 million to a company called Chiang Wei Ltd for its role in facilitating a prepayment agreement between the government and Sahara Energy Resources DMCC.

In a letter accompanying the invoice, the loan committee’s chair, Biel Jock Thich, wrote that the fee was “based on the success of facilitating the loan and helping to serve the dire economic needs of this time.” The letter does not indicate whether or not Sahara Energy was made aware of the arrangers fee.

Chiang Wei Ltd is registered in both South Sudan and neighbouring Kenya, and is half owned by the former U.S. college basketball player Kueth Duany, according to corporate registration documents. Duany is listed as the company’s CEO on his LinkedIn profile.

Sahara Energy Resources is a subsidiary of the Swiss-Nigerian Sahara Group, and is named in the previously unpublished oil ministry report as one of the companies that received oil shipments in 2018 and 2019. The other companies are Dubai-based BB Energy (Gulf) DMCC, and the commodity-trading giant Glencore in partnership with a South Sudanese firm called Trinity Energy.

Sahara Energy Resources, BB Energy, Chiang Wei Ltd, and Kueth Duany did not respond to OCCRP’s request for comment. The Technical Loans Committee and Office of the President also did not respond to a request for comment.

Glencore was also a creditor to Chad’s national oil company, which in 2014 borrowed about $1.45 billion against future oil production from the Switzerland-based trader. But plunging oil prices meant that Chad struggled to meet its repayments. In 2017, more than half the money Chad spent on repaying this loan went toward interest and restructuring fees, according to the finance ministry.

The Republic of Congo faced similar problems after the government borrowed more than $1 billion from commodity traders including Glencore and Trafigura, while the state-owned oil company took out loans of its own. Public spending was cut in half between 2015 and 2018, as debt repayments consumed oil revenues.

Glencore referred OCCRP to its public disclosure of purchases of South Sudanese oil worth $425 million in its 2018 Payments to Government Report and additional information about its prepayments, including to Chad’s government, in its annual reports.

The vast debts that both Chad and the Republic of Congo owed to commodity traders has also stalled relief from the International Monetary Fund. Before accessing the desperately-needed relief funds, the governments agreed to restructure their private loans.

Low prices have again plunged oil-dependent economies into crises, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made the situation worse. The World Bank has called on private lenders to do more to support a debt-suspension initiative by the Group of 20 major economies, which is intended to ensure the poorest countries can use their limited resources to fight the pandemic rather than service loans.

“It doesn’t really make sense for the commercial creditors to continue taking in, requiring and legally enforcing payments from the ... poorest countries that have been struck by both the pandemic and the deepest economic recessions since World War II,” the bank’s president, David Malpass, told Reuters.